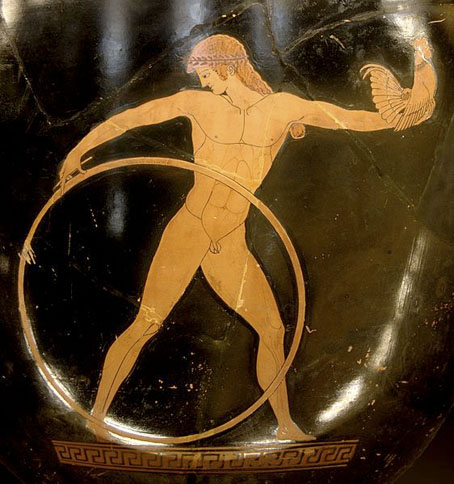

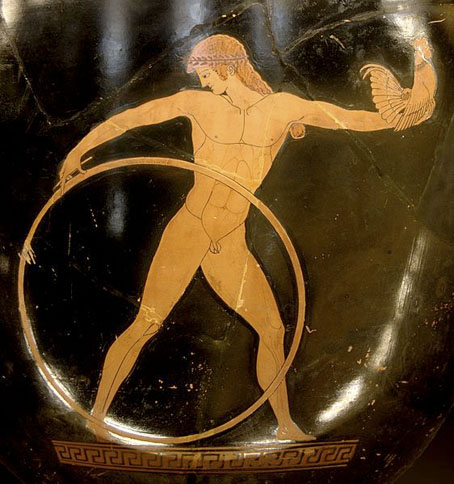

Ganymede from an Attic red-figure bell-krater, ca. 500–490 BC.

And ye Megarians, at Nisæa dwelling,

Expert at rowing, mariners excelling,

Be happy ever! for with honours due

Th’ Athenian Diocles, to friendship true

Ye celebrate. With the first blush of spring

The youth surround his tomb: there who shall bring

The sweetest kiss, whose lip is purest found,

Back to his mother goes with garlands crowned.

Nice touch the arbiter must have indeed,

And must, methinks, the blue-eyed Ganymede

Invoke with many prayers—a mouth to own

True to the touch of lips, as Lydian stone

To proof of gold—which test will instant show

The pure or base, as money changers know.

Theocritus, Idyll XII, translated by Edward Carpenter.

One Ancient Greek tradition yet to be revived by the International Olympic Committee is the Diocleia, an annual contest held in the Dorian city of Megara. William Smith’s A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1882) gives a brief explanation:

DIOCLEIA, a festival celebrated by the Megarians in honour of an ancient Athenian hero, Diocles, around whose grave young men assembled on the occasion, and amused themselves with gymnastic and other contests. We read that he who gave the sweetest kiss obtained the prize, consisting of a garland of flowers. (Theocrit. Idyll. xii. 27, &c.) The Scholiast on Theocritus (l. c.) relates the origin of this festival as follows – Diocles, an Athenian exile, fled to Megara, where he found a youth with whom he fell in love. In some battle, while protecting the object of his love with his shield, he was slain. The Megarians honoured the gallant lover with a tomb, raised him to the rank of a hero, and in commemoration of his faithful attachment, instituted the festival of the Diocleia.

So the Diocleia was primarily a same-sex kissing contest, a detail that 19th century accounts do their best to skirt around, as they tended to do when faced with the unavoidable yet unacceptable sexual proclivities of the Ancient World. Here’s another account from a typewritten thesis by Ernest Leslie Highbarger, Chapters in the History and Civilization of Ancient Megara (1923):

Diocles

In his honor public games, the Diocleia, were celebrated. These were as important at Megara as were the Pythia and Eleusinia elsewhere. According to Megarian belief, Diocles was a Megarian ruler of Eleusis. But the Alexandrine tradition claimed that he was an Athenian who had fled to Megara for some cause and had become a hero after dying in defense of a boy friend. […] These Diocleia were held at the beginning of spring. The prize is said to have been a crown of flowers and was presented to the boy who gave the sweetest kiss. Boeckh and Reinganum, however, maintain that we must not limit such a contest to kissing but must extend it to contests in general such as the ones in which Diocles was victorious. But if we are to judge by the elegies of Theognis, boy-love was as common at Megara as in other parts of Greece and the osculatory contest at the games may have constituted no insignificant part.

Edward Carpenter, on the other hand, being a pioneering activist for gay rights, regarded these festivals as one of the many valuable precedents that might be used to argue a defence for same-sex relations:

Further [Bethe] suggests that the competition which yearly took place among the youths at the tomb of the great hero and lover, Diocles, in Megara – and which is known to us through Theocritus (Idyll xii.) – had a similar origin; and represented the survival of actual betrothals which once were celebrated there, as at a holy place. There is certainly something very grand about this whole conception and manifestation of the Uranian love among the Dorians. The wonderful stories – treasured in the hearts of the Greek peoples for centuries – of heroic bravery and mutual devotion inspired by it; the high seriousness with which it was cultivated both as a political safeguard and as a means of the education of youth, the religious sanction and dedication to the gods, and withal the absolute recognition of its human and passional origin, cannot fail to make us feel that here was a great people with a unique message for the world. Certainly we shall never in modern times understand this love until we realise this quality of it and its immense capabilities.

Intermediate Types among Primitive Folk (1914)

Dorian: Yes, the word is the origin of Dorian Gray’s first name, and Oscar Wilde was fully aware of its referring to proscribed passions. He was sufficiently well-acquainted with Greek poetry to pen a poem of his own to Theocritus so would have been very familiar with the Idylls and their paean to the Diocleia.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Achilles by Barry JC Purves