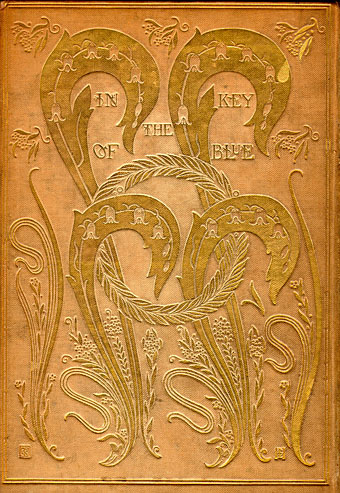

I probably overspent a little on this charity-shop purchase, the third edition (published 1918) of In the Key of Blue by John Addington Symonds (1840–1893), a personal selection of writings first published in 1893. First edition copies sell for over a thousand pounds so this was an opportunity to acquire something close to the original without breaking the bank. The book is significant for two reasons: on a decorative level the cover design is one of my favourites by book designer (he preferred the term “book builder”) Charles Ricketts. The first editions have the design blocked in gold on cream cloth (below); a few copies were made with blue cloth but Ricketts apparently changed the colour after worrying that reviewers would joke about “Reckitt’s Blue” a popular laundry product. The contraposed curves of the leaf shapes pre-empt the Art Nouveau style which only started to emerge a year or two later.

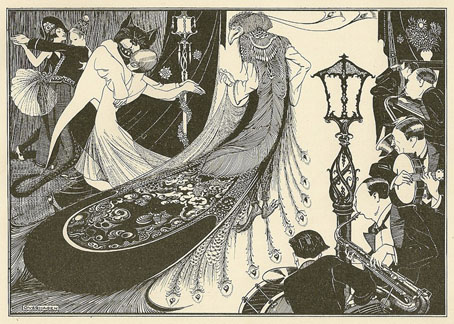

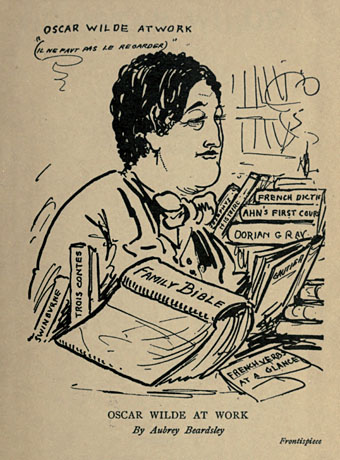

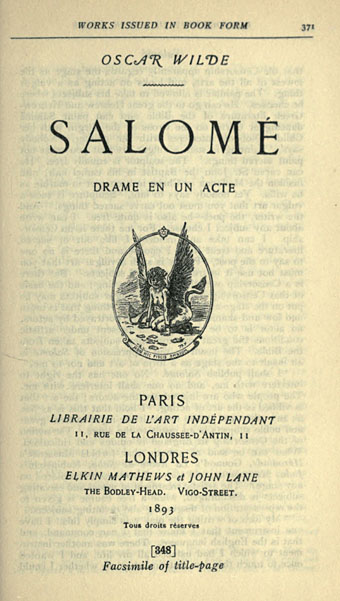

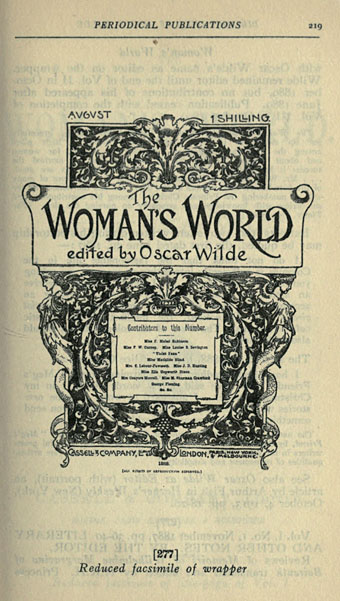

The other notable feature of Symonds’ book is its being one of the more outspoken manifestations of the author’s advocacy for what he called “a man’s love for a man”. Symonds was a pioneer of what are now called gay studies: in addition to accurately translating the love sonnets of Michelangelo which previous translators had heterosexualised, his 1873 study A Problem in Greek Ethics sought to show 19th-century readers that the Ancient Greek culture they so admired had an indisputable history of same-sex relationships running through its core. This was only one side of Symonds’ work but it was an admirably continual thread. I often think of Symonds and Oscar Wilde as twinned in this respect: Wilde made frequent use of Greek attitudes as a justification for his views on love; both men had to perform a careful balancing act, trying to advocate the unacceptable without drawing too much attention to their own proclivities. If Wilde was the public advocate for Uranian desire then Symonds was a kind of think-tank man, labouring behind the scenes to bring to light the historical precedent. Finally, both men were connected by Charles Ricketts, a friend of Wilde’s who designed and illustrated a number of Wilde’s early editions.

In the Key of Blue was published in the last year of Symonds’ life by which time much of his previous equivocations had been abandoned. In homoerotic terms it’s far more out of the closet than pre-trial Wilde ever dared to be. The title piece is a poem which presents eight studies of an unnamed “you”, a figure seen by the poet in various Venetian settings, painted in a range of colours with blue as the dominant tone. I have the poem in another book; taken alone as it is there it seems mildly homoerotic—the ecstatically observed subject is obviously male—but remains ambiguous enough for any subtext to be a matter of interpretation. In the collected edition Symonds adds additional text that picks apart the poem, explaining the origin of each setting. Thus we learn that the mysterious “you” is a 19-year-old Venetian porter named Augusto whom the author had befriended. The explanatory paragraphs discuss the artistic intent of the poem, its depiction of contrasted tones and colours, while the circumstantial details quietly remove all the ambiguity from its paean to male youth.

Elsewhere in the book, there’s a discussion of male love among the Greeks, culled from Symonds’ earlier researches, then in Clifton and a Lad’s Love, written thirty years earlier, we have another piece of alternating poetic verse and prose description. Part seven of the poem could hardly be less equivocal:

I saw a vision of deep eyes

In morning sleep when dreams are true:

Wide humid eyes of hazy blue,

Like seas that kiss the horizon skies.Then as I gazed, I felt the rain

Of soft warm curls around my cheek,

And heard a whisper low and meek:

“I love, and canst thou love again?”A gentle youth beside me bent;

His cool moist lips to mine were pressed,

That throbbed and burned with love’s unrest:

When, lo, the powers of sleep were spent;And noiseless on the airy wings

That follow after night’s dim way,

The beauteous boy was gone for aye,

A theme of vague imaginings.Yet I can never rest again:

The flocks of morning dreams are true;

And till I find those eyes of blue

And golden curls, I walk in pain.

Anyone wishing to read In the Key of Blue can find most of Symonds’ work online. Project Gutenberg has all his major texts available while the Internet Archive has a scan of the 1918 edition, albeit in slightly better condition than my copy.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Greek games

• Charles Ricketts’ Salomé

• Achilles by Barry JC Purves

• Der Eigene: Kultur und Homosexualität

• Charles Ricketts’ Hero and Leander