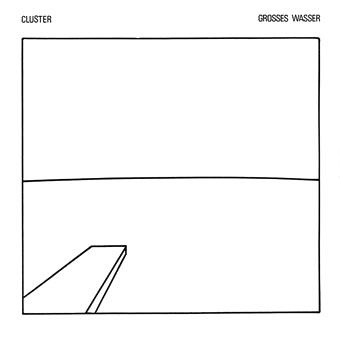

Grosses Wasser (1979) by Cluster. Cover art by Dieter Moebius.

• RIP Dieter Moebius: one half of Cluster (with Hans-Joachim Roedelius), one third of Harmonia (with Roedelius and Michael Rother), and collaborator with many other musicians, including Brian Eno and Conny Plank. Geeta Dayal, who interviewed Moebius for Frieze in 2012, chose five favourite recordings. From 2008: Cosmic Outriders: the music of Cluster and Harmonia by Mark Pilkington. At the Free Music Archive: Harmonia playing at ATP, New York in 2008. Live recordings of Cluster in the 1970s have always been scarce but in 1977 they played a droning set at the Metz Science-Fiction Festival, a performance that was broadcast on FM radio (the Eno credit there seems to be an error).

• “I’ve since had the feeling that, if the attacks against The Satanic Verses had taken place today, these people would not have defended me, and would have used the same arguments against me, accusing me of insulting an ethnic and cultural minority.” Salman Rushdie on the fallout from the Charlie Hebdo killings.

• “The effect of these memories is to make you think you know the film better than you do, and wonder what it’s like actually to sit down and watch it.” Michael Wood on rewatching Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958). Related: Tipping My Fedora on the film’s source novel, Badge of Evil (1956).

“To me, it’s simple,” he says. “Fantasy became as bland as everything else in entertainment. To be a bestseller, you’ve got to rub the corners off. The more you can predict the emotional arc of a book, the more successful it will become.

“I do understand that Game of Thrones is different. It has its political dimensions; I’m very fond of the dwarf and I’m very pleased that George [R R Martin], who’s a good friend, has had such a huge success. But ultimately it’s a soap opera. In order to have success on that scale, you have to obey certain rules. I’ve had conversations with fantasy writers who are ambitious for bestseller status and I’ve had to ask them, ‘Yes, but do you want to have to write those sorts of books in order to get there?’”

Michael Moorcock talking to Andrew Harrison about fantasy, science fiction, the past and the present.

• “Architects love Blade Runner, they just go bonkers. When I was working on the film, it was all about, let’s jam together Byzantine and Mayan and Post-Modern and even a little bit of Memphis, just mash it all together.” Designer and visual futurist Syd Mead talking to Patrick Sisson.

• “Lucian of Samosata’s True History reads like a doomed acid trip,” says Cecilia D’Anastasio, who wonders whether or not the book can be regarded as the earliest work of science fiction.

• Mixes of the week: A Tribute to Dieter Moebius by Vegan Logic, and another by Totallyradio.

• The Phantasmagoria of the First Hand-Painted Films by Joshua Yumibe.

• Islamic Geometric: calligraphic tessellations by Shakil Akram Khan.

• Michael Prodger on The Dangerous Mind of Richard Dadd.

• A chronological list of synth scores and soundtracks.

• Touch Of Evil (Main Theme) (1958) by Henry Mancini | Badge Of Evil (1982) by Cabaret Voltaire | Touch Of Evil (2009) by Jaga Jazzist