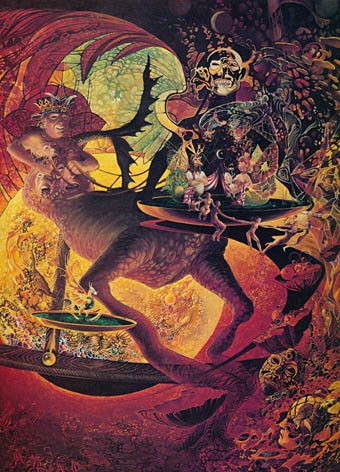

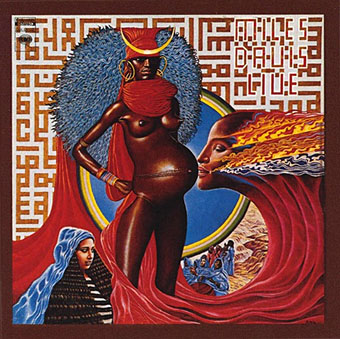

Estate of Man (1967).

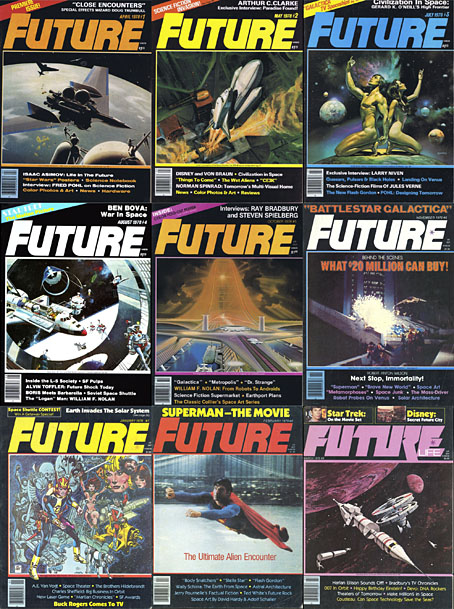

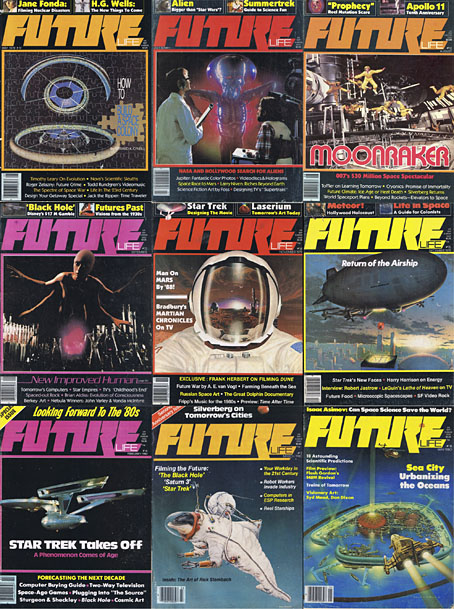

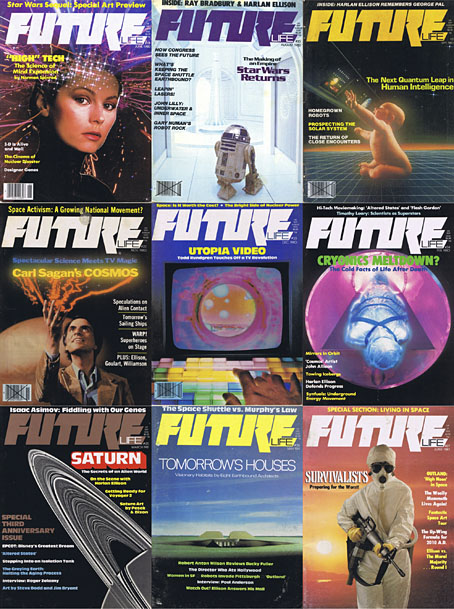

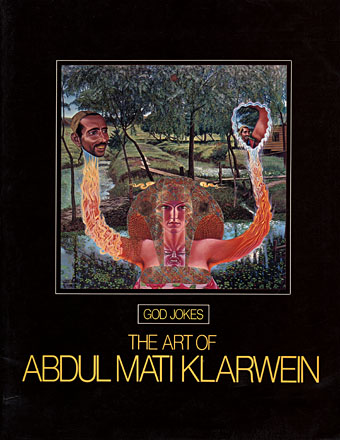

A short tribute to American artist Nick Hyde who I’ve been informed died last month. Hyde’s extraordinary paintings were featured here a few years ago after I found a copy of Visions (1977), an art book devoted to artists of the loosely-affiliated California Visionary school. Most of the paintings in the book are a type of fantastic art (not to be confused with fantasy art) that owes much to the hippy mysticism that later became codified as “New Age”, a vague term which covers a lot of territory. Several of the paintings were featured in the early issues of OMNI magazine but I don’t recall Nick Hyde’s art being among them. Hyde’s early paintings are darker and stranger than those of his Visions contemporaries, and they were ones I inevitably preferred to the rest, hence my earlier post highlighting his work. There isn’t much else I can say about him other than pointing to the official website and posting the following appraisal by Walter Hopps from Visions. All the paintings here are from Visions, and several of them (Abraxas in particular) look like they need to be seen at a much larger size.

Cryptyde (1967).

I am not trying to clean myself of impurities, but to venture into a very real situation. I consider myself a true visionary—it comes to me and I flow with it. My imagery is always a dance.” Nick Hyde, 1976

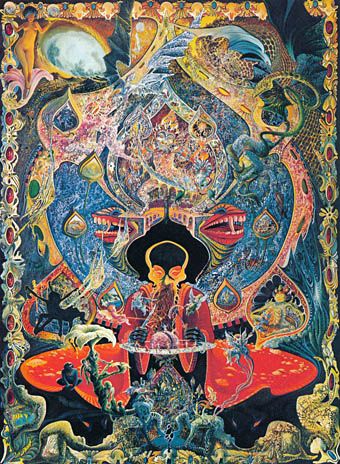

The powerful nature of Nick Hyde’s art stands in certain important ways vividly apart from that presented here by his visionary colleagues. Rather than scenes of cosmic calm, serene process, or peaceful resolution, Hyde pours forth effulgent compositions of both hallucinatory intensity and tumultuous activity. The myriad visual events and details brought forth in an all-at-once total vision in Hyde’s paintings give rise to a unique tension between what seems the most violent of struggles and the most delicate of dances. In maintaining qualities of such polarity Hyde reveals a mastery of a sinuous, insinuating line structure that both divulges and dissolves images.

Inside Out Breaking Free (1968).

In his extraordinary allegorical painting Estate of Man, human figures are disgorged from a Gothic tracery of lines that suggests the network of nerves of a livid inner eye. Closer inspection reveals the jaws of a hell-mouth that swallows these figures and assimilates them as functioning fibers in a self-conceiving infernal machine. At upper right, however, in a zone of apparent transcendence, Hyde paints a luminist landscape at the moment of sunrise. It is perhaps where one is to find redemption in the Eye of God: or is it merely the burning earth that bears man to offer him to hell?

BethAnn (1969).

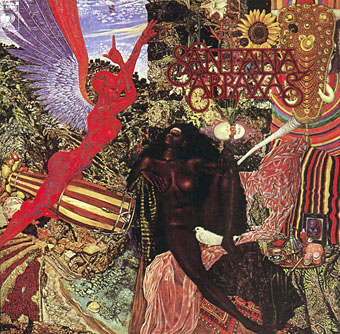

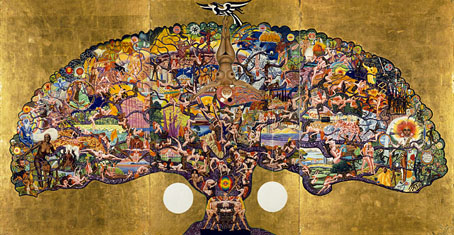

Hyde’s painting Abraxas touches on a note of subtle, mordant humor: the mythoid monster and his serpent-headed mate entwined in an infernal lair is, at the same time, a gentleman with his lady, reclining at ease, casually smoking. and telephone in hand. A clock—on the fire-place mantle at the right of the composition—is without hands, and ornamented by two barely perceptible figures. They repeat in reverse the pose of the two polymorphic companions. Abraxas, a god of good and evil, exists in a world abandoned of time, of rhythmic mimesis, of smoldering mockery. —Walter Hopps

Urp (1970).

Abraxas (1971).

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Visions and the art of Nick Hyde