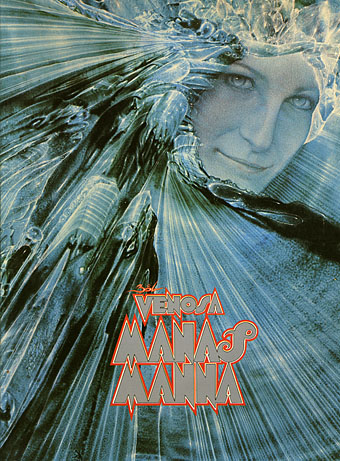

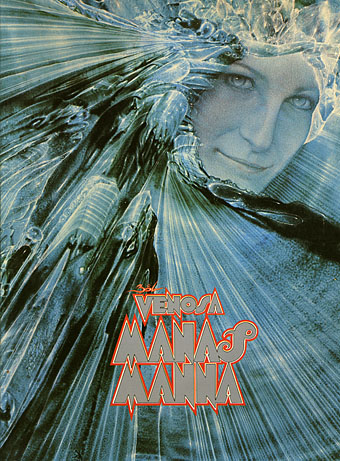

A few years back, while experimenting with the hallucinogens, I experienced visions of a dynamic energy in constant high-velocity motion, crystallizing and manifesting in a form which could only be described as angelic. Potential energy, crystallizing energy and structured energy were all visible in the same instant…time and space transcended. These visions, and a new-found awareness of spirit brought about through worship and meditation, were too powerful not to be expressed: a translation had to be attempted.

Robert Venosa, Manas Manna, 1978.

I only discovered a few days ago that American artist Robert Venosa had died last month. As with the late Sibylle Ruppert there’s the inevitable wish for some wider acknowledgement of the passing of these unique talents.

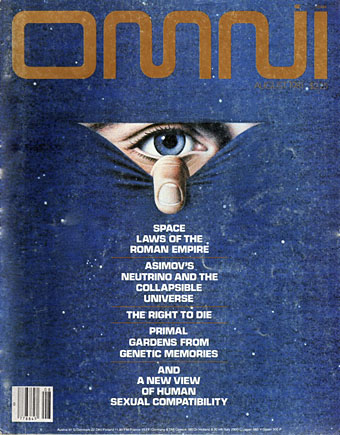

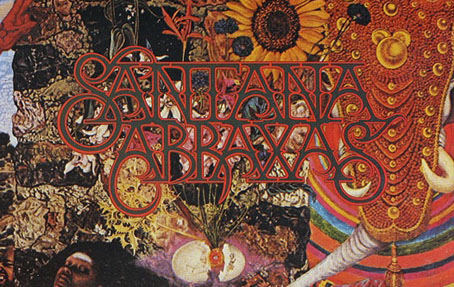

Millions of people have seen one of Venosa’s creations without being aware of it: in 1970 he designed the logo/title for Santana’s Abraxas album (the one with the amazing Mati Klarwein cover), a design which is still in use today. But it’s as a painter that he ought to be remembered. Manas Manna was the first collection of Venosa’s art published by Peter Ledeboer’s Big O imprint in 1978, and could be found on bookshelves that year with a pair of equally remarkable auto-monographs: Mati Klarwein‘s God Jokes and the first English edition of HR Giger‘s Necronomicon. All three artists were aware of each other (Venosa was friends with the other two), and all had managed the difficult feat of having their work sold in art galleries whilst also being visible to a much larger audience on album covers. All three books were eagerly plundered that year by the art team of OMNI magazine whose early issues made heavy use of paintings by Klarwein, Giger, Venosa, De Es Schwertberger and others. Of this Venosa has said:

OMNI was the first to give the artist equal credit with the author…something that to this day is still not seen in any other newsstand magazine. OMNI also put Fantastic Realism, Surrealism, Visionary, and every other type of ‘Fantasy’ art, square into the public’s eye. I and my colleagues owe OMNI a large measure of gratitude for its uncompromising stance and visionary concepts.

Venosa had been an art director at Columbia Records in the 1960s, a job he abandoned after he met Mati Klarwein and decided he’d rather devote his time to painting. Despite describing Klarwein in his book as his painting master, only a couple of his pictures are reminiscent of Klarwein’s distinctive style. Many of Venosa’s works are more loose and abstract than Klarwein’s tableaux, extending the processes of decalcomania which Max Ernst refined in works such as Europe After the Rain (1942) and The Eye of Silence (1944) to create stunning views of cosmic eruptions and vistas of crystalline beings rendered in a meticulous, hyper-realist manner. Many of his pictures could serve as illustrations for the later chapters of JG Ballard’s The Crystal World.

If the lazy definition of psychedelic art refers merely to shapeless forms and bright, clashing colours, Venosa’s art is psychedelic in the truest sense, an attempt to fix with paint and brush something revealed by a profound interior experience. This was deeply unfashionable by 1978, of course, but he carried on working anyway, and there are further book collections for those interested in his paintings. The Venosa website has a small selection of his extraordinary pictures although they really need to be seen at a larger size.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The album covers archive

• The fantastic art archive