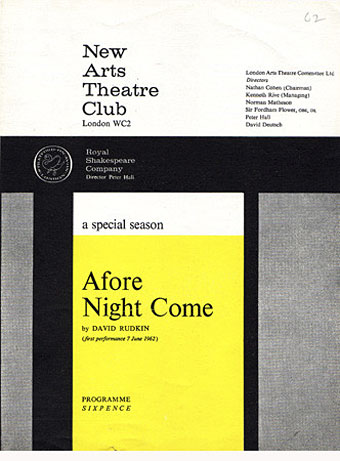

RSC programme, 1962.

Not a review, this, you can’t really review a stage play you’ve never seen. Following the re-viewing of David Rudkin’s White Lady I’ve gone back to some of the published plays. If all you know of Rudkin’s work is his television drama, the plays are instructive for showing the consistency of his themes across the years. The recent resurgence of interest in Penda’s Fen and Artemis 81 has seen Rudkin’s work included among that group of film and TV dramas that Rob Young memorably labelled Old Weird Britain (after Greil Marcus and The Old, Weird America), a loose affiliate that would include films such as The Wicker Man and Blood on Satan’s Claw, television works by Nigel Kneale and Alan Garner (The Owl Service, Red Shift), and the BBC MR James adaptations, one of which, The Ash Tree, was also written by Rudkin.

If the Old Weird Britain lies at an intersection between different dramatic forms—ghost story, horror story, science fiction, historical drama—then not all of Rudkin’s work would fall into the intersection, but two of the plays—The Sons of Light and his first staged work, Afore Night Come—could be coaxed into the charmed circle: The Sons of Light, with its sinister human experiments taking place underground, has ties to Artemis 81, while Afore Night Come is another piece about (intentional or otherwise) human sacrifice in rural England. I hadn’t read Afore Night Come until last week, and was struck by its similarity to John Bowen’s Robin Redbreast (1970), a more deliberately ritualistic piece of work. In its first act Afore Night Come is an almost documentary-like account of a day in the life of workers hired to pick the pear harvest in an orchard outside Birmingham; the eruption of violence in the second act is certainly foreshadowed but seems less premeditated than in Robin Redbreast, a factor which has apparently shocked many audiences. During its performances in the early 1960s the tendency was to see the play in the light of Harold Pinter and Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, it’s only in retrospect that a connection with more generic works emerges. There’s also a connection to White Lady via the pesticide spraying about which the workers are continually warned, and whose advent coincides with the moments of violence.

Sight and Sound, August 2010. Illustration by Becca Thorne.

A couple of other things are worth noting: until 1968 all the plays performed in Britain were vetted by the Lord Chamberlain’s office who would routinely strike out any material deemed offensive or irreligious. Knowing this I was surprised by the recurrence of the word “fuck” in Rudkin’s script, and also the hint of same-sex attraction between two of the male characters, a detail that would usually have been removed. It seems that plays pre-1968 could be performed without censorship if the theatre was declared to be a private club for the evening (a similar state of affairs helped evade some film censorship) which is what happened with Afore Night Come in 1962. Given this, and the incident of a decapitated head being rolled across a London stage (probably the first since the Jacobeans, says Rudkin), it’s easy to see why audiences at the time might have felt assaulted, although the play still won the Evening Standard Drama Award that year. Sexual ambiguity/ambivalence or outright homosexuality have been a continual thread in Rudkin’s drama yet he’s seldom been given much credit for this pioneering work. A year after Afore Night Come there was Rudkin’s first play for television, The Stone Dance, a piece which sounds like another potential addition to the works in the Old Weird Britain catalogue. Rudkin describes it thus:

A Revivalist pastor pitches his crusade tent within a Cornish stone circle. His repressed son becomes sexually obsessed with an outward-going local boy, and suffers a hysterical loss of speech. A storm blows the pastor’s tent away, and amid the stones, their primal purity reasserted, by the boy’s accepting touch the son is healed.

I believe that, prior to this, no tv play had overtly treated homosexual emotions as a central theme. (In Britain at this time, any gay sex could incur a prison sentence of up to two years.)

Many of the TV plays from the 1960s are now lost so there’s no guarantee that we’ll ever see this, a shame considering that Michael Hordern and John Hurt were the leads. No guarantee either that we’ll see any staging of the more interesting plays like The Sons of Light and The Triumph of Death which seem to be too eccentric for theatre directors. The scripts can at least be picked up relatively cheaply. To date there’s only Afore Night Come that seems to be revived with any regularity. Michael Billington, a long-time champion of Rudkin, reviews the Young Vic production from 2001 here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• White Lady by David Rudkin

• The Horror Fields

• Robin Redbreast by John Bowen

• Red Shift by Alan Garner

• Children of the Stones

• Penda’s Fen by David Rudkin

• David Rudkin on Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr