What we have here is a very creditable 67-minute film adaptation of the Symbolist novel by Georges Rodenbach. Ronald Chase directed, co-wrote the screenplay with Pier Luigi Farri, and also photographed the production with a small company of English actors in the city of Bruges. The film has recently been given a high-definition restoration and made available on the director’s Vimeo page. Chase describes his adaptation as a low-budget affair, the footage being originally intended for screening during performances of Die Tode Stadt by Eric Korngold, but it doesn’t come across as cheap or amateurish thanks to a professional cast and authentic locations. Rodenbach’s novel is distinguished by its early use of photographic illustrations, most of which are views of the canals of Bruges. Here we get to see the church steeples and crow-step gables from the viewpoint of a camera drifting along the same swan-filled waterways.

It’s a long time since I read Rodenbach’s novel so I can’t judge this version in any detail although my memories are of a dreamier narrative than the one the film delivers. Chase credits the story as being “suggested” by the novel but the broad outline follows Rodenbach, with a grieving widower (Richard Easton, whose character is unnamed in the film) meeting a dancer (Kristin Milward) who seems to be the double of his recently deceased wife. The dancer works with a troupe of performers who stage a nocturnal masque for the tormented man, an event which fails to alleviate his confusion or his anguish.

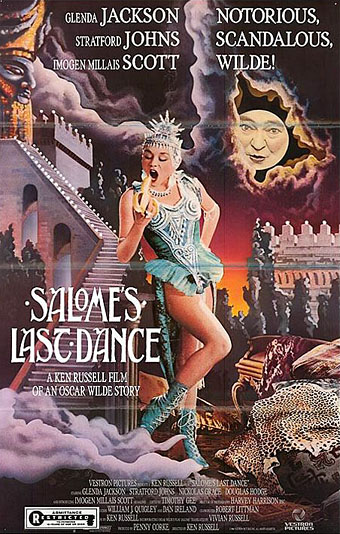

Chase’s film resembles one of the literary adaptations the BBC used to make throughout 1970s and 80s, modest and serious, and certainly of a quality that it could have been broadcast as a part of the Omnibus arts strand or in a late slot on BBC 2. Among the performers are a Pierrot character played by Anthony Daniels, an actor most people will know for his role as a gold robot in a space opera, and Nickolas Grace, who appeared as Oscar Wilde a decade later in Ken Russell’s Salomé’s Last Dance. There’s a touch of the diabolical Russell (and James Ensor) in the later masque scenes when the performers don papier-mâché masks, and a nun gets chased around a church. The mask-making is credited–very surprisingly–to Winston Tong, an artist and musician best known for his association with Tuxedomoon. I was hoping we might see more of the gloomy canals and equally gloomy architecture but the buildings and bridges that we do see look just as they would have done in Rodenbach’s day. If you want more there’s always the paintings and drawings of Fernand Khopff and Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, or the photographs in the novel itself.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Bruges in photochrom

• Bruges panoramas

• Bruges-la-Morte