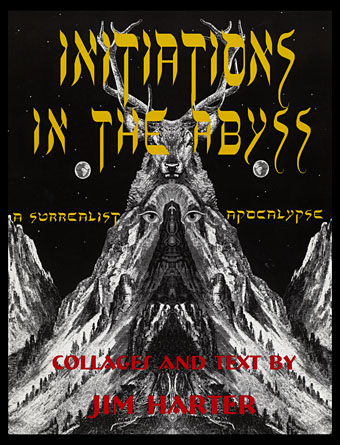

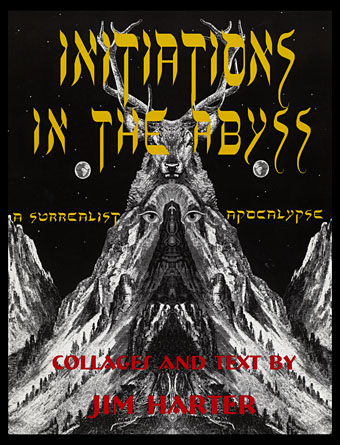

Among the many books inspired or influenced by the events of September 11th, 2001, Jim Harter’s Initiations in the Abyss: A Surrealist Apocalypse is one of the more obscure titles, and one you’re unlikely to hear about elsewhere. Harter is an American artist and archivist best known for his collections of wood engraving illustration published by Dover Publications, Harmony Books, Bonanza Books and others. I mentioned his work recently in a piece about steampunk illustration which will be appearing later this month at Tor.com. Harter’s books are invaluable source material for the style of collage popularised by Max Ernst and Wilfried Sätty. Harter was a friend of Sätty’s, with collages by the pair appearing in Harter’s Picture Archive for Collage and Illustration (1978).

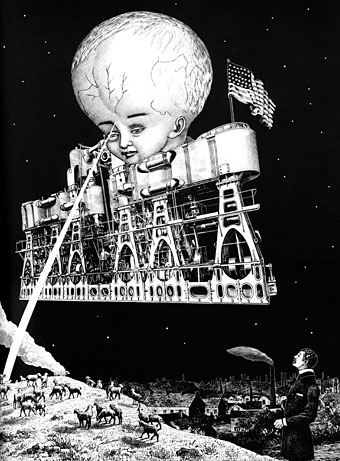

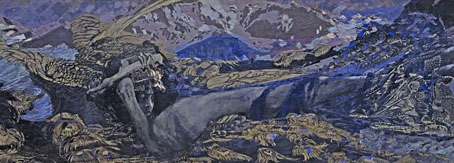

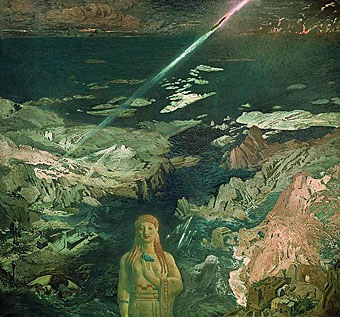

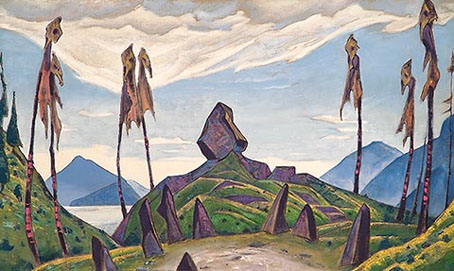

The first collection of Harter’s collages, Journeys in the Mythic Sea: An Innerspace Odyssey, appeared in 1985. Initiations in the Abyss is the follow-up featuring work which dates from 1986, some of which was exhibited in 1988 at the Nicholas Roerich museum in New York. The book wasn’t published until 2003, however, and in his introduction Harter acknowledges the influence the events of the past two years had on his conception of the work as a whole. The book is reminiscent of Sätty’s Time Zone (1973), a book with a similar intent in its use of Surrealist collage techniques to make satirical or polemical points as well as to create striking and fantastic images. With both artists it’s the latter works which I find most successful. There’s a limit, for example, to how effectively our world can be represented using pictures which are over a hundred years old, and without the single-minded focus and attack of a John Heartfield the polemic can risk seeming diffuse or glib.

Harter’s book is divided into four parts—Mutant Faces of the Form Destroyer, The Holy Abattoir, The Archive of Dreams and Mystery Play—with 72 full-page plates printed on glossy paper. The quality of the printing is so good it makes me wish that Sätty and Ernst could receive the same treatment. In addition there’s a very long introductory essay by Harter which somewhat contradicts his Surrealist intent by explaining at great length some of the philosophy behind pictures whose interpretation he wants left to the reader. Near the end of his piece he says:

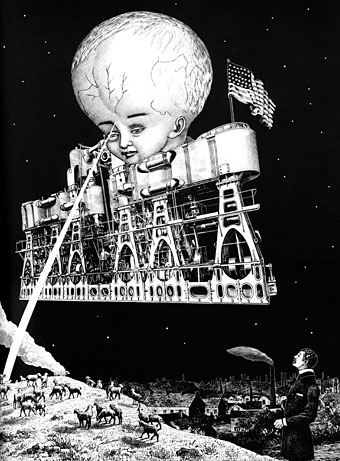

It could be said that the purpose of the collages in the present book’s first two sections is to ring an alarm bell. The canaries in the mine are dying and it is time to do something. At the same time, the images of the last two sections are intended as a kind of mystery play. They suggest a movement in another direction: a quest to seek a more universal vision, one where we can perhaps discard our religious fanaticism, ethnocentrism, and myths of apocalypse, and instead create a world of greater unity and harmony, eventually becoming one human family. On another level entirely, this work might be seen as a kind of shamanic soul journey, where all false attachments, beliefs, and illusions are destroyed through an ego death experience before the soil is allowed to proceed to dimensions of healing and revelation. Thus the first two sections might be seen as an encounter with what the Tibetans call the “wrathful deities,” spirits that mirror back one’s own unconscious darkness.

The last two sections of the book feature the best of his dream-like imagery, some of which are a match for Sätty’s superb creations. The examples here are mostly from the end sections. Further examples can be seen on this page where the plates have been coloured by the artist.

Initiations in the Abyss is available to buy direct from the publisher, Wings Press, while some of Harter’s psychedelic poster art can be seen here and here.

Continue reading “Initiations in the Abyss: A Surrealist Apocalypse”