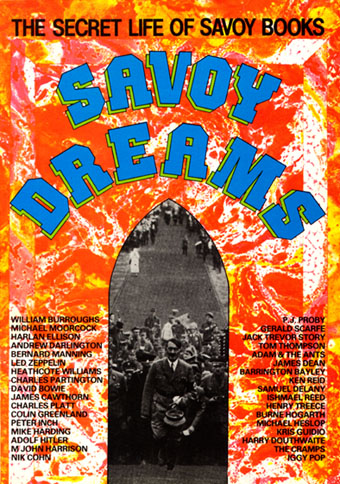

Savoy Books, 1984.

A couple more recent arrivals that feature my work. These are of minority interest but worth noting since academic articles don’t always travel beyond a small audience of subscribers.

A recent issue of Foundation (The International Review of Science Fiction), Volume 45.1, number 123, contains an article by Mark P. Williams, Underground Assemblages: Savoy Dreams and The Starry Wisdom. This examines the legacy of New Worlds magazine under the editorship of Michael Moorcock (from 1964 to 1974) via two writing collections, Savoy Dreams (Savoy Books, 1984) and The Starry Wisdom (Creation Books, 1994). The two collections are very different: Savoy Dreams, edited by David Britton and Michael Butterworth, was an eclectic overview of Savoy’s publishing endeavours up to that point. Among the original writing there’s fiction by Butterworth, M. John Harrison (the first publication of the Viriconium story, Lords of Misrule) and others, plus a reaction by Michael Moorcock to William Burroughs’ Cities of the Red Night, a book that Savoy had contracted to publish before police harassment forced the company’s bankruptcy. The rest of the book is taken up with press reviews of Savoy books.

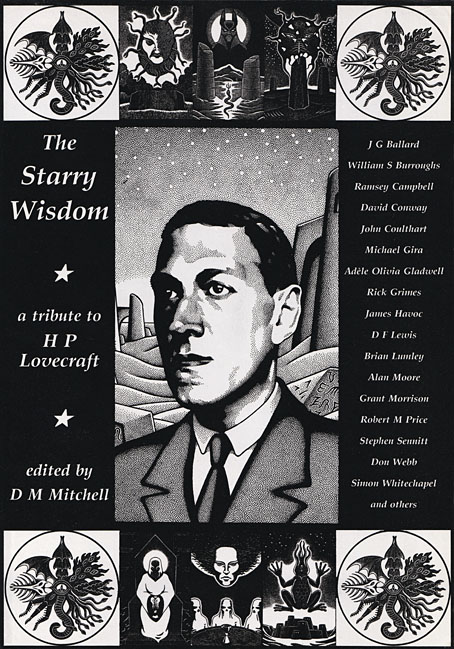

Creation Books, 1994. Cover art by Peter Smith.

The Starry Wisdom should require less of an introduction since the book has been in print since 1994, and has a small, possibly notorious, reputation among HP Lovecraft enthusiasts. Editor DM Mitchell felt that the assembling of post-Lovecraftian fiction up to that point had been too cosy and insular: too many story collections were being edited and written by groups of friends in the genre fiction “community”, with the result that the stories were often stale and complacent. The startling newness of Lovecraft’s imagination in comparison to many of his contemporaries in Weird Tales seemed to have been bled away into pastiche, a process that began soon after Lovecraft’s death. Mitchell’s solution was to commission original pieces of Lovecraft-inspired work from writers outside the genre world, notably Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, and newcomer David Conway; he also reprinted pieces that would never appear elsewhere as Lovecraftian fiction, including Wind Die. You Die. We Die. by William Burroughs, and Prisoner of the Coral Deep by JG Ballard. Burroughs and Ballard connect directly to New Worlds, of course (Ballard wrote about Burroughs for the magazine), while the pair cast a shadow over many of Savoy’s book productions. Both Savoy Dreams and The Starry Wisdom featured comic strips; Tales of the Cramps by Kris Guidio appeared in Savoy Dreams, while The Starry Wisdom contained strips by Mike Philbin & James Havoc, Rick Grimes, and the first publication of my own adaptation of The Call of Cthulhu.

I was surprised—and pleased—that my comic strip receives a fair amount of scrutiny in Williams’ piece. My Lovecraft strips have received almost no attention from the comics world, a consequence of having been printed by book publishers and distributed to book shops. (A rare exception was this recent piece by Matt Maxwell.) When you’ve been overlooked in this manner it’s a surprise to find your work receiving serious evaluation from an entirely different quarter. Mark P. Williams’ essay examines the contents of both collections, my strip included, as “assemblages”. This is a valid critique in the case of the Cthulhu strip since Lovecraft’s story is itself an assemblage of what seems at first to be unrelated data. The comic adaptation assembles a range of cultural references—some genuine, others invented—to parallel the narrator’s investigation, and even uses genuine documents in places, including columns from The New York Times. I don’t know if Williams has seen the blog post I made that points out many of the cultural references but he notes some of the more overt ones, such as Joseph Conrad appearing as the doomed Professor Angell, Arnold Böcklin’s The Isle of the Dead, and so on. While I was drawing the strip I was trying to imagine the story as an RKO production, a hybrid of two island films—The Most Dangerous Game and King Kong—and Orson Welles’ unmade Heart of Darkness. These references, many of which aren’t very obvious, were largely for my own amusement. The series I created with David Britton that followed the Lovecraft strips, Reverbstorm, puts assemblage and cultural reference at the forefront.

Cover art is my illustration for Remnants from Lovecraft’s Monsters, edited by Ellen Datlow.

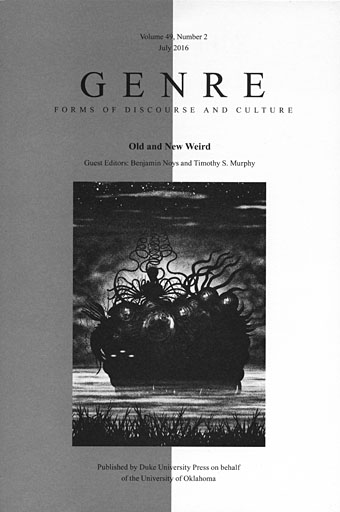

The Cthulhu strip and the Reverbstorm series—now collected as Lord Horror: Reverbstorm—are the subject of a very perceptive piece by Benjamin Noys in the latest edition of Genre, an academic journal published by Duke University Press. This number of the journal is a kind of Weird special edited by Benjamin Noys and Timothy S. Murphy. Noys’ Full Spectrum Offence: Savoy’s Reverbstorm and the Weirding of Modernity is the final article in a publication that examines aspects of the “Old Weird” (ie: the Lovecraft-era Weird Tales) and contrasts it with the more recent “New Weird”. The latter was a short-lived label coined by M. John Harrison in 2003 for a range of fiction that was ignoring genre boundaries, and consciously developing the Weird as a project. China Miéville was one of the most visible proponents of the New Weird, and Harrison’s term emerged in part as a response to Miéville’s fiction. Miéville is interviewed in this issue of Genre where, as usual, he has some very worthwhile things to say. He prefers the term “haute Weird” for the original manifestation, possibly because it avoids the negative connotations of the word “old”.

A spread from part 7 of Reverbstorm.

Benjamin Noys’ article is lengthy and resists easy summary, but it begins by investigating the way my work on the Lovecraft strips permeated the Lord Horror comics and dictated some of the imagery, in particular the architectural forms and eruptions of monstrosity. Later discussion concerns the way that Reverbstorm forces the Weird and Modernism together, a collision that I believe is still unique anywhere, never mind in the comics medium. Noys’ piece has given me a lot to think about, not least for its being the first substantial critical appraisal of Reverbstorm. The series is a difficult one, being deliberately excessive and avant-garde, and presenting the reader with a torrent of interrelating cultural references. Many of these are itemised in the appendix but the success (or not) of their working together, and the potential sparking of connections, depends very much on the prior knowledge of the individual reader. Noys is not only knowledgeable but adept at forging his own connections while situating the series in the larger context of the Weird, old (or haute) and new. Even without the inclusion of my work inside the journal and on the cover, I’d recommend this issue of Genre to anyone with an interest in the subject. One of the reasons I favour the Weird as a chosen work label is the way it evades (or ignores) generic boundaries. Years ago I realised that many of the things I liked the best in the arts were the chimeras, those works that transgress boundaries and created new hybrids. No surprise then that I enjoy a genre that refuses easy definition. There aren’t many masts I pin my colours to but the Weird is one of them.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Weird