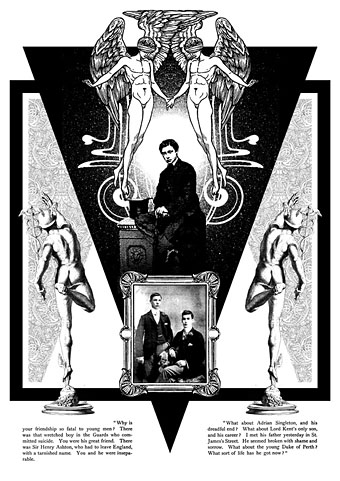

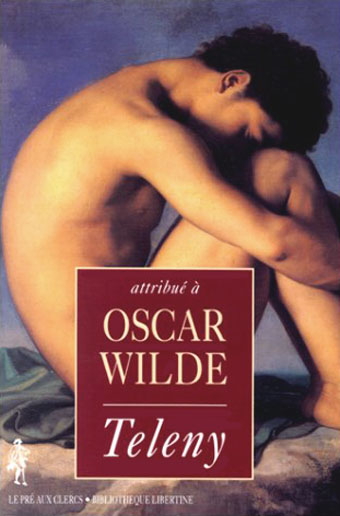

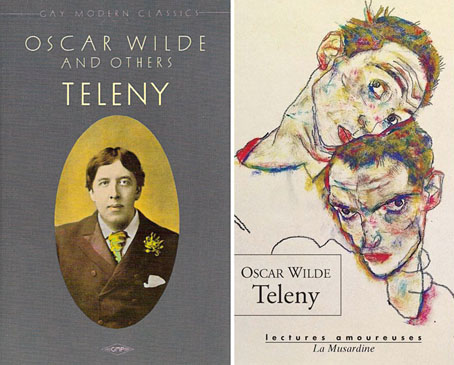

Bibliothèque Libertine edition (1996).

The quintessence of bliss can, therefore, only be enjoyed by beings of the same sex… Teleny

More Wildeana, and yes, it’s that painting again… Teleny is an authorless, explicitly homoerotic novel often attributed to Oscar Wilde although what evidence there is regarding its creation points to its being the work of several hands. The book was published in a limited edition by Leonard Smithers in 1893 then subsequently reissued in a variety of editions which, being illicit and copyright-free, suffered excisions and textual amendments. Smithers was a good friend of Wilde’s. In addition to being Victorian London’s most prominent pornographer (a sign in his Bond Street shop window proudly declared “Smut is cheap today”), Smithers also financed The Savoy magazine, and kept Aubrey Beardsley solvent after the artist’s commissions dried up following Wilde’s imprisonment in 1895.

The convoluted history of Teleny begins with its mysterious origin, recounted here by Beardsley scholar Brian Reade in Philippe Jullian’s 1969 Wilde biography:

Charles Hirsch, a Parisian bookseller, came to London in 1889 and opened a shop in Coventry Street where he sold Continental books and newspapers. Wilde was a frequent customer of his, and Hirsch used to obtain for him Alcibiades enfant à l’Ecole and The Sins of the Cities of the Plain. Many of these were reprints of well-known works of this character. Towards the end of 1890 Wilde brought into the shop a thin paper commercial-style notebook, wrapped up and sealed. This he instructed Hirsch to hand over to a friend who would present his card. Shortly afterwards, one of Wilde’s young friends whose name Hirsch had forgotten by the time he recorded the incident called at the shop and after showing Wilde’s card took away the packed-up notebook. A few days later the young man came back and handed the manuscript to Hirsch, saying another man would call and collect it in a similar manner. In all, four men seem to have taken away and returned the manuscript, and the last left the wrapper undone. Succumbing to temptation, Hirsch opened the parcel and read the contents of the notebook, the leaves of which were loose. On the cover there was a single word TELENY; inside about 200 pages of a novel which appeared to be a collaborative effort. No author’s name was given. The handwritings were various; there were conspicuous erasures, cuttings-out and corrections. Hirsch believed that some of the writing was Wilde’s. In due course Hirsch gave the manuscript back to Wilde. He next came across Teleny when he found it had been printed by Leonard Smithers in an edition privately issued and limited to 200 copies, with only the imprint ‘Cosmopoli’ at the bottom of the title page, and the date 1893. In this printed version, Paris had been substituted for London as the scene of the action, and there were certain differences of detail. There was an added sub-title Or the reverse of the Medal, and the Prologue had been cut out. When Hirsch got to know Smithers in 1900, he asked about the book, and was told that Smithers had wished not to upset the self-respect of clients by leaving the story with a London background. There was also Des Grieux, A Prelude to Teleny which was announced for publication by the Erotica Biblion Society in 1908. One can go over the names and literary mannerisms of some of the better-remembered persons in his circle in 1890, but to associate any of them with the authorship of Teleny would be difficult. Copies of Teleny in the 1893 edition are very rare indeed. The British Museum has one, but those in private possession have been reduced in number no doubt by executors and others who considered them unfit for anything else than fire. A new edition was brought out by the Olympia Press of Paris, and in it Wilde was definitely, but mistakenly, credited with the authorship; and an expurgated version was produced in paperback form by Icon in 1966, with an introduction by Montgomery Hyde.

Neil McKenna in The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde (2003) is convinced of Wilde’s involvement whereas Richard Ellmann firmly dismissed the notion in his own more substantial biography. Some of the dissent is perhaps a result of competing agendas, in McKenna’s case a determination to establish a firmly gay persona for the author. McKenna explores Wilde’s sex life in detail, something that Ellmann frequently skates over. Ellmann, meanwhile, has a better grasp of Wilde’s literary prowess and evidently thought that Teleny didn’t adequately match the rest of the author’s work. I remain agnostic on the issue while being struck by the frequent use in Teleny of flower metaphors which the narrator deploys when describing the object of his affection. Having recently read McKenna’s book (which quotes throughout from Wilde’s letters), and re-read The Picture of Dorian Gray, it’s impossible to avoid Wilde’s continuous recourse to flower imagery when referring to people or even items of furniture. One of the more striking examples of this was his description of Aubrey Beardsley and sister Mabel in a letter to Ada Leverson: “What a contrast the two are—Mabel a daisy, Aubrey the most monstrous of orchids.” On the debit side of the authorship argument I’d say that Wilde is unlikely to have invented the central relationship between Camille de Grieux and his Hungarian lover, René Teleny. McKenna’s book makes it clear that Wilde preferred younger men, particularly teenagers, and would no doubt have outlined a different story had he been the sole originator.

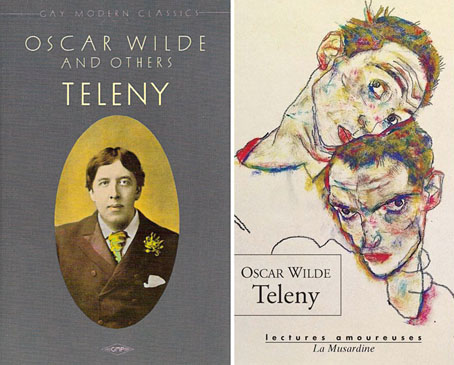

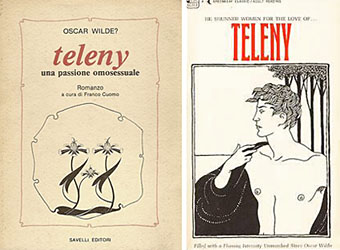

left: Gay Men’s Press edition (1986); right: La Musardine edition (with Egon Schiele cover, 2009).

Everyone who discusses Teleny, however, is agreed that its prose is more finely-wrought than much general writing of the period, never mind the era’s pornography. The sexual description is powerfully erotic and gives the lie to the canard (perpetuated by the egregious Auberon Waugh and his annual Bad Sex in Fiction Award) that describing sex is almost always a mistake. Describing anything poorly is a mistake, the challenge is to do the thing well, and Teleny describes the encounters of its pair of lovers better than many writers would manage today.

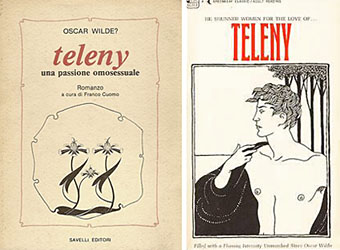

Genuine (left) and pastiche (right) Beardsley designs.

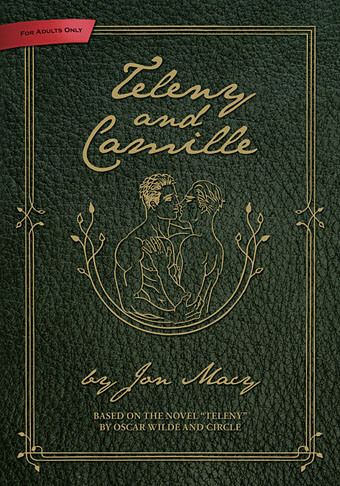

With such an intriguing work it’s always a boon if there’s further discussion on the subject, and the Wilde connection pays off here with a whole section of the Oscholars website being devoted to the book. Of particular note is John McRae’s introduction to a revised and textually corrected edition published in 1986 by London’s Gay Men’s Press. Jason Boyd, meanwhile, argues that the book could never be wholly attributed to Wilde. Also present is a page showing different cover designs for the various editions, some of which are shown above. As well as the inevitable Wilde portraits and Beardsley designs there’s the surprise appearance of Flandrin’s Jeune Homme Assis au Bord de la Mer on several editions. Other pages at Oscholars include plates from an illustrated edition of the novel whose publisher and illustrator, Uday K Dhar, forbid reproduction elsewhere, an all-too-common example of copyright paranoia which ensures the audience for their work remains a limited one. By contrast, artist Jon Macy has an entire site devoted to his comic strip adaptation of Teleny. His black-and-white drawing and attention to detail combine to make his book another item for the shopping list.

Update: The Oscholars site appears to have folded so the links now connect to archived pages.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Oscar Wilde archive

• The recurrent pose archive