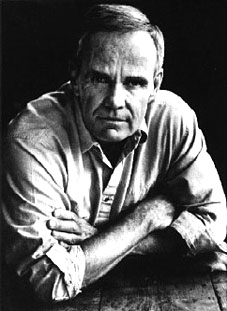

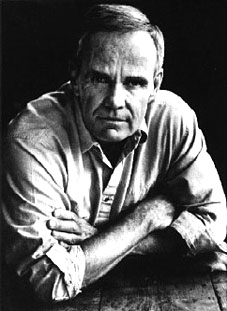

Cormac McCarthy’s venomous fiction

Richard B. Woodward

The New York Times, April 19, 1992

“YOU KNOW ABOUT MOJAVE RATTLESNAKES?” Cormac McCarthy asks. The question has come up over lunch in Mesilla, N.M., because the hermitic author, who may be the best unknown novelist in America, wants to steer conversation away from himself, and he seems to think that a story about a recent trip he took near the Texas-Mexico border will offer some camouflage. A writer who renders the brutal actions of men in excruciating detail, seldom applying the anesthetic of psychology, McCarthy would much rather orate than confide. And he is the sort of silver-tongued raconteur who relishes peculiar sidetracks; he leans over his plate and fairly croons the particulars in his soft Tennessee accent.

“Mojave rattlesnakes have a neurotoxic poison, almost like a cobra’s,” he explains, giving a natural-history lesson on the animal’s two color phases and its map of distribution in the West. He had come upon the creature while traveling along an empty road in his 1978 Ford pickup near Big Bend National Park. McCarthy doesn’t write about places he hasn’t visited, and he has made dozens of similar scouting forays to Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and across the Rio Grande into Chihuahua, Sonora and Coahuila. The vast blankness of the Southwest desert served as a metaphor for the nihilistic violence in his last novel, Blood Meridian, published in 1985. And this unpopulated, scuffed-up terrain again dominates the background in All the Pretty Horses, which will appear next month from Knopf.

“It’s very interesting to see an animal out in the wild that can kill you graveyard dead,” he says with a smile. “The only thing I had seen that answered that description was a grizzly bear in Alaska. And that’s an odd feeling, because there’s no fence, and you know that after he gets tired of chasing marmots he’s going to move in some other direction, which could be yours.”

Keeping a respectful distance from the rattlesnake, poking it with a stick, he coaxed it into the grass and drove off. Two park rangers he met later that day seemed reluctant to discuss lethal vipers among the backpackers. But another, clearly McCarthy’s kind of man, put the matter in perspective. “We don’t know how dangerous they are,” he said. “We’ve never had anyone bitten. We just assume you wouldn’t survive.”

Finished off with one of his twinkly-eyed laughs, this mealtime anecdote has a more jocular tone than McCarthy’s venomous fiction, but the same elements are there. The tense encounter in a forbidding landscape, the dark humor in the face of facts, the good chance of a painful quietus. Each of his five previous novels has been marked by intense natural observation, a kind of morbid realism. His characters are often outcasts—destitute or criminals, or both. Homeless or squatting in hovels without electricity, they scrape by in the backwoods of East Tennessee or on horseback in the dry, vacant spaces of the desert. Death, which announces itself often, reaches down from the open sky, abruptly, with a slashed throat or a bullet in the face. The abyss opens up at any misstep.

Continue reading “Cormac McCarthy’s venomous fiction”