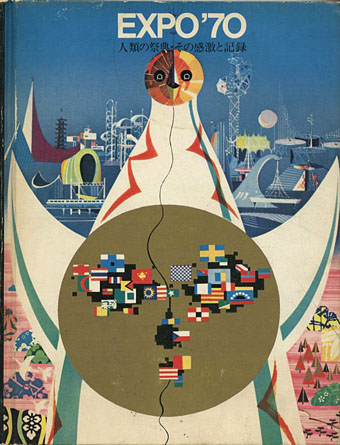

Taro Okamoto’s Tower of the Sun on the cover of an Expo ’70 guide.

• Last week I was watching the restored print of Howard Brookner’s excellent William Burroughs documentary, Burroughs. Among the later scenes are shots of the writer visiting Britain in the autumn of 1982 for the Final Academy events, a visit also recorded on Super-8 by Derek Jarman, and by the video cameras of the Haçienda nightclub at a reading I was fortunate to attend. Included in the Brookner film are brief snatches of an interview with Burroughs for BBC Radio 1 by John Peel’s producer, John Walters, something I missed when it was first broadcast.

• Taro Okamoto’s Tower of the Sun was built in Osaka for Expo ’70, and unlike many one-off expo buildings has managed to survive years of neglect and threats of demolition. Visitors to the Tower may now explore the restored “Tree of Life” interior, although places are limited so it’s necessary to book in advance. Related: Expo ’70 at ExpoMuseum, and Tower Of The Sun (1997) by Shonen Knife.

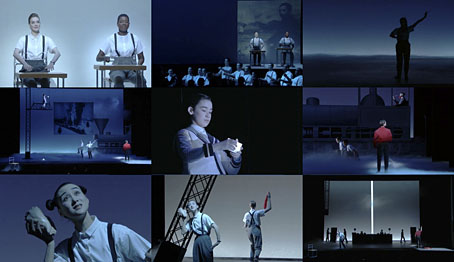

• Also at Dangerous Minds this week: a 1969 TV recording of Krzysztof Penderecki’s notorious The Devils of Loudon, an opera based on the same Aldous Huxley book as Ken Russell’s The Devils, and which includes (among other things) a singing nun enduring a forced enema.

• The new Cavern Of Anti-Matter album, Hormone Lemonade, is released this week. XLR8R has a preview. Related: an old/undated mix by Tim Gane for The Brain radio show here.

• Milton Glaser on some of his favourite posters. Milton Glaser Posters, a book collecting 427 poster designs, is published this week by Abrams.

• The Ghosts of Empty Moments: Christopher Burke reviews M. John Harrison’s You Should Come with Me Now.

• Mixes of the week: FACT mix 644 by Susanna, and XLR8R Podcast 534 by Pär Grindvik.

• Emily Temple found 25 of the most expensive books you can buy on the internet.

• Towers Of Dub (1992) The Orb | Tower Of Our Tuning (2001) by Broadcast | Television Tower (2001) by Monolake