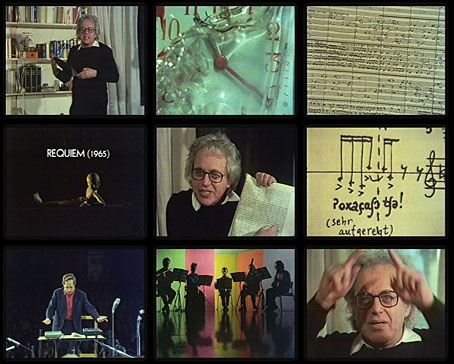

It’s unlikely that anyone will be stuck for anything to watch during the next few days but you could do worse than spend an hour with this documentary about the music of composer György Ligeti. I’ve mentioned this several times over the years, it’s one of my favourite films by the late Leslie Megahey, my favourite director of TV arts documentaries. All Clouds are Clocks was made for the BBC’s long-running Omnibus arts strand, and is unique among all the films made for that series in being broadcast twice (in 1976 and 1991), with the second broadcast appending new footage to the original film.

The film as a whole is fairly simple by today’s standards, an interview with the composer in his studio intercut with extracts from Ligeti recordings and performances. After years of documentaries filled with hyperactive editing and inane comments from celebrity interviewees Megahey’s straightforward approach is a considerable relief. You have the music, and you have the composer talking about the music; that’s it. Especially commendable is that there’s no mention at all of the use of Ligeti’s recordings as film scores. If the BBC made a film like this today (which they wouldn’t in any case) the first thing you’d see would be clips from Stanley Kubrick films.

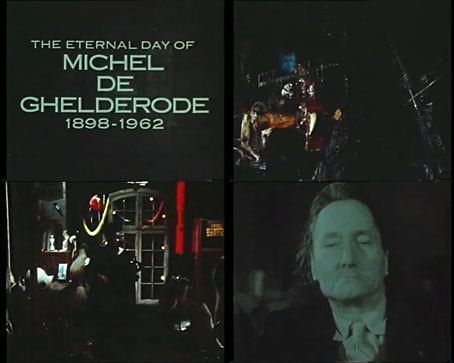

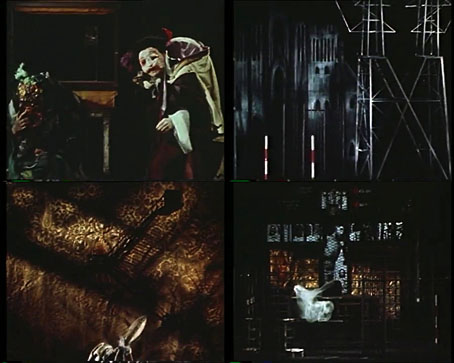

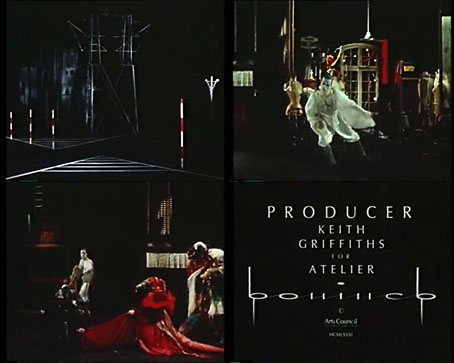

As is often the case in Megahey’s documentaries, the director himself is the narrator, and in this one he’s also the off-screen interviewer as he was in his celebrated Orson Welles documentary. The illustrative episodes include melting plastic clocks, the slow awakening of a wooden puppet, and a performance of Poème symphonique, the composition which requires the priming and operation of 100 metronomes. Ligeti comes across as good-humoured and approachable, a serious artist but one whose general demeanour never seems loftily superior to ordinary human concerns the way Stockhausen often did. Ligeti’s manner confirms the sense of humour behind compositions like the one for the metronomes, and even more so in the choral/orchestral work Nouvelles Aventures. The latter is shown in an extract from a filmed performance at the Roundhouse, London, in 1971, a concert conducted by Pierre Boulez which provokes raucous laughter from the audience when a tray loaded with crockery is hurled into a bin. There’s humour of a blacker variety in the 1991 section which includes a description of Ligeti’s “anti-anti-opera”, Le Grande Macabre, based on a play by Michel de Ghelderode. This was Ligeti’s only operatic work, and I think it may be the only Ligeti composition I still haven’t heard in full. Most stagings are a riot of grotesque costuming and set design (the setting is a place called “Breughelland”) so it obviously needs to be seen as well as heard.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• György Ligeti, a film by Michel Follin

• Leslie Megahey, 1944–2022

• Le Grand Macabre

• Leslie Megahey’s Bluebeard

• Metronomes