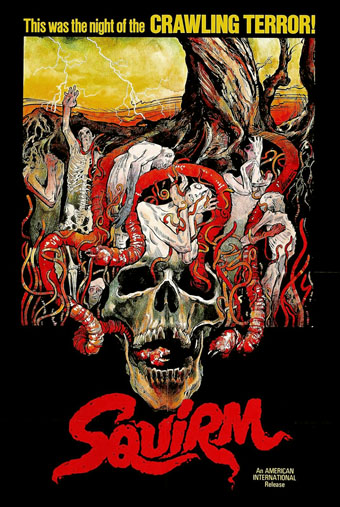

Among the film viewing this past week there was Psychomania (1973), another advance Blu-ray courtesy of the BFI. Americans may know this as The Death Wheelers, a more accurate (if clumsily literal) retitling, although Psychomania does a better job of grabbing the attention. In the micro-genres of the horror film the occult biker picture is a niche with few entries; offhand I can only think of Werewolves on Wheels (1971), a low-grade American production. Most biker films are American so Psychomania is unusual for being British (with an Australian director, Don Sharp), and with a pitch that’s memorable if nothing else: biker gang kill themselves then return from the dead so they can cause mayhem with impunity. The script was the work of Arnaud d’Usseau and Julian Zimet whose only other credit is for a curious chiller made the year before, Horror Express. This was a British/Spanish period piece with a good cast (Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing, Telly Savalas) that’s notable—and often overlooked—for being another film based on John W. Campbell’s SF story “Who Goes There?”.

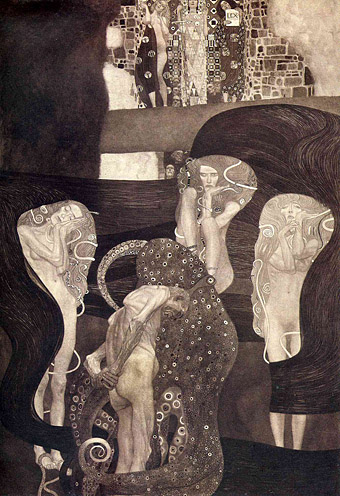

The Seven Witches and The Living Dead.

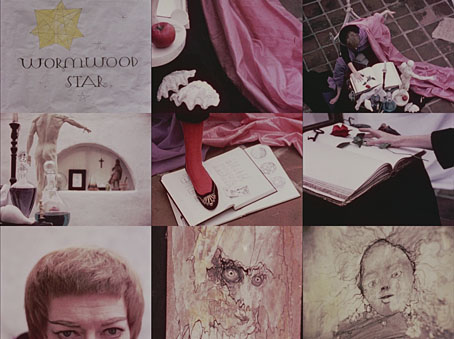

Psychomania also has a decent supporting cast despite its frequent swerves into absurdity. Since the subject is a Home Counties’ bike gang, the leader, Tom Latham (Nicky Henson), has a mother (Beryl Reid) who lives in a country house with a very modish interior: all abstract art, scatter cushions, leather furniture and Trimfones. Mrs Latham is the local table-tapper and may also be a witch, although it’s never clear whether the scene of her offering her son to the Devil is Tom’s hallucination or a replaying of past events. Tom’s father has died after some unspecified supernatural encounter in a mysterious locked room where Tom later has the vision of his being sold to the Devil. Then there’s Shadwell (George Sanders), ostensibly the butler of the household but devilish enough to shrink from a cross when it’s offered by grateful séance attendees. Reid and Sanders lend the proceedings some gravitas, even if Sanders (in his final role, and not well at the time) seems to have stooped far below his usual level. Nicky Henson makes a charismatic leader of bike gang The Living Dead, although his tight leather pants, and the shiny leather gear worn by the others, belong to an earlier decade. This is biker gear as imagined by people remembering The Wild One or The Leather Boys, and a long way from the reeking, never-washed denim “originals” favoured by Hell’s Angels and their ilk.

Chopped Meat (Harvey Andrews) sings Riding Free while Tom is being buried.

It’s probably too much to expect of a low-budget horror film, but watching Psychomania again had me thinking that an opportunity was missed to more accurately reflect the real bike gangs of Britain in the 1970s. Biker culture was a country-wide phenomenon at the time; boys I was at school with were too young to own motorbikes but many had brothers who did, and had picked up from them the fetishising of dying British manufacturers such as Triumph, Norton and BSA. (The Living Dead all ride Triumphs.) A few years later I was hanging around with the bikers who were always present among any group of metal-heads, many of whom were too poor to own British bikes but behaved as though they did. The bikerdom of the 70s had little to do with the bike groups of earlier decades even if the bike brands remained the same. The new model, of course, was California’s Hell’s Angels whose first British chapters appeared in London in the late 1960s, and whose legend was popularised by Hunter S. Thompson in Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs (1967). Every biker seemed to have read to Thompson’s book, and the presence of Hell’s Angels on British soil led to the swift founding of many imitation groups, forbidden from using the name without Californian approval but grouping themselves under similar handles. A measure of the culture’s appeal to the popular British imagination may be found in the many biker exploitation novels published by New English Library through the mid-70s.

Given all this you’d expect biker culture to be more prevalent in British cinema of the period but the examples are so few there’s really only Psychomania and Sidney J. Furie’s The Leather Boys (1964). The latter documents the pre-Hell’s Angels biker scene via a pseudonymous gay novel that makes similar connections to Kenneth Anger’s almost contemporaneous Scorpio Rising. The gay content is diluted in the film but there’s enough there to make it seem surprisingly bold for the time. Furie’s bikers are a tame bunch compared to The Living Dead, they only want to ride their bikes, not play hogs of the road, and the film as a whole is kitchen-sink-on-wheels, with a link to A Taste of Honey (1961) via Rita Tushingham.

Abby meets dead Tom at the stone circle.

Psychomania is glossier—well, it’s in colour!—and aims for lurid AIP-style mayhem even if such antics seem out-of-place in leafy Surrey. When Tom’s mother inadvertently gives him the secret of bodily resurrection he goes out and kills himself; after his return from the grave (on a motorcycle!) his gang eagerly follow his example. The film runs out of steam when it becomes apparent that The Living Dead’s idea of making the most of their post-death freedom is the same harassing of pedestrians and other motorists as before. The only question is whether Tom’s girlfriend, Abby (Mary Larkin), will kill herself and join them in an eternity of trashing supermarkets. Abby’s equivocation is signalled by her being the only member of the gang who doesn’t wear leather. The film touches on folk horror with the location of “The Seven Witches”, a circle of standing stones which the gang use as their meeting place, and where they bury Tom after he plunges off a bridge. As with The Wicker Man, which was being filmed around the same time, there’s even an acoustic song interlude from one of the more hippyish bikers.

George Sanders and Beryl Reid indulge in some home Satanism.

Psychomania was always a welcome sight when it used to appear on late-night television. The combination of bikers and occult rites is unusual enough to sustain the attention even if the implications of the premise go unexplored. Unlike The Wicker Man, however, or the excellent Blood on Satan’s Claw (1970), Psychomania‘s disparate threads fail to cohere, and the film is held together largely by its sense of black humour. Don Sharp’s direction manages a couple of clever single-take sleights, and the soundtrack by John Cameron is very good. Cameron wrote a great deal of library music so was adept at capturing the essence of a style. Psychomania‘s soundtrack plays on the rock grooves of the period, and the theme was issued as a single credited to “Frog” (after the possibly supernatural amphibian that Tom finds in a graveyard).

The film looks excellent on Blu-ray albeit grainier in low-light scenes than other BFI transfers. The audio is also more noise-reduced than I’d prefer. The disc includes the usual wealth of BFI extras: interviews with the surviving cast members; a short interview with John Cameron; an amateur film, Roger Wonders Why (1965), about a pair of Christian (!) bikers; and a black-and-white short for Shell narrated by John Betjeman about the Avebury stone circle. George Sanders is absent from the extras since he killed himself shortly after finishing work on the film. As Michael Weldon notes with typical drollery in The Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film, Sanders didn’t return from the dead on a motorcycle. A pity.

Psychomania is released on 19th September.