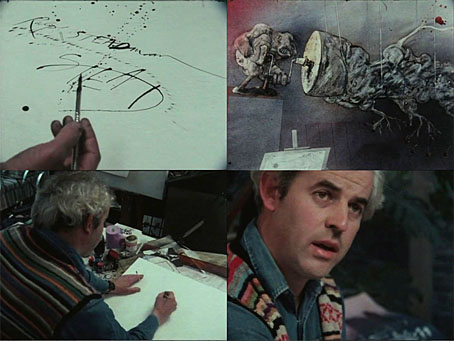

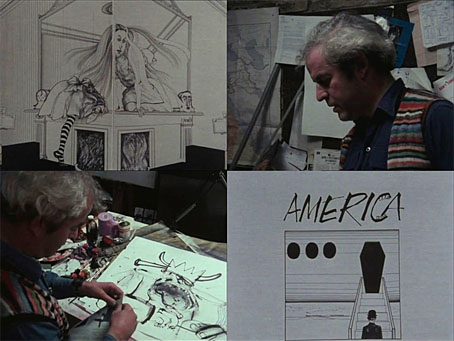

This is the kind of thing I like to see: 35 minutes of an artist doing nothing but drawing or talking about drawing. Michael Dibb’s profile of Ralph Steadman is the earliest BBC portrait of the artist, made for the long-running Arena arts series. Arena was launched in 1975 but films from the series prior to 1980 are rare things on the internet. This one concentrates on Steadman’s creation of a drawing for a new book, The Cherrywood Cannon, an anti-war story by Dimitri Sidjanski. In between work on the drawing Steadman describes how he approached illustrating Alice Through the Looking-Glass, and his drawings of the Patty Hearst trial, before repairing to the local pub where he sketches the regulars. Hunter S. Thompson only receives a passing mention, which may surprise some viewers; if it’s Thompson you’re after then you’ll want to see Fear and Loathing on the Road to Hollywood, the 1978 Omnibus profile of the writer which features Steadman again, plus many more of his drawings.

The Arena film is relatively short but valuable for the insight it gives into Steadman’s technique: no preliminary drawing, for example, he starts with ink on a blank sheet of paper. I was amused to see him using a spray diffuser to fill in the background. This is a kind of lung-powered airbrush, an angled tube which you place in your bottle of ink then blow through to create spray effects. I used one myself for a while as a rougher (and cheaper) alternative to an airbrush, before graduating to using old toothbrushes which are easier to control when spattering ink. I’d always assumed that Steadman used an airbrush himself but seeing his loose approach to sketching it makes sense that he’d like the grainier, less predictable textures created by a diffuser.

Michael Dibb’s film is at the producer’s Vimeo channel together with many other excellent documentaries, including John Berger’s landmark Ways of Seeing series. Vimeo changed its policies recently, insisting that you sign in if you want to see something that hasn’t been rated by the user (ie: most of the things there). This can be avoided by using the mobile Vimeo app, an option which also gives you better search facilities.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Ralph Steadman record covers

• Beardsley and His Work