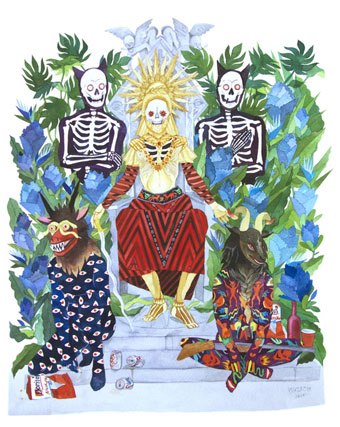

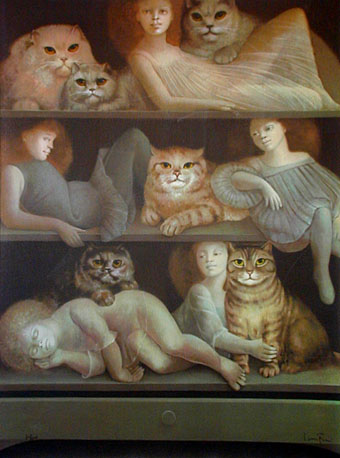

You’ll Never Be Alone, Even In Death (2014) by Stacey Rozich.

• “But the CD-R format, which eventually replaced the mix tape, turned out to be a technological letdown. ‘CD-Rs are just such an unstable format,’ Margolis says. ‘When you made 10 cassettes, the 10 cassettes generally played. If you made 10 CD-Rs, 8 of them played and 2 of ’em skipped. So that partially explains why people are going back to cassettes—it’s a cheap format that actually works.'” A huge article by Lisa Hix on the history and resilience of cassette tapes.

• “The word speculative comes from speculum, or mirror, and with speculative music the goal is to mirror the hidden processes of nature in sound.” David Metcalfe on Hawthonn, Coil and imaginal landscapes.

• Mixes of the week: FACT Mix 498 by The Cyclist, and Adventures In Sound And Music 28 May 2015 compiled by Joseph Stannard.

Nabokov was an intimate writer. His reticences, his formal estrangements, his denial of interest in any reality beyond the text all need to be measured against that. Maximum closeness: not the closeness of ostentatious empathy but the closeness of one mind addressing another in the most thrilling terms. He speaks into the ear, sometimes dripping a little poison. He contrives to have a reader identify intimately with a protagonist or narrator, but even that is not enough; the reader receives secret handshakes from the author himself, behind a narrator’s back.

Michael Dirda quoting from Nabokov in America by Robert Roper

• Books old and new: The Encyclopedia of the Dead by Danilo Kis, and Stranger Days by Rachel Kendall.

• At Dangerous Minds: Il caso Valdemar (1936), a short Italian adaptation of the Edgar Allan Poe story.

• Lustpiel is “a new online magazine for gay, lustful literature”. And a fair amount of art and porn.

• “Q: Is there any subject that is never acceptable to joke about?” No, says Curtis Brown.

• Machines Are Obsolete, a new piece by Pye Corner Audio for the Ghost Box label.

• Ishbelle Bee (see yesterday’s post) is interviewed at SFFWorld and Book Swoon.

• Laura June on the life of Djuna Barnes, stunt reporter and shocking modernist.

• Stream the debut LP from Ghost Harmonic, a new John Foxx project.

• Portraits of the BDSM community by Natasha Gornik.

• Rainer Werner Fassbinder: 10 essential films

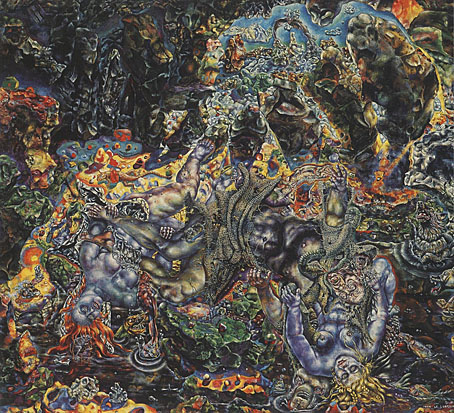

• Loplop

• Mirrorball (2009) by John Foxx & Robin Guthrie | Mirror (2012) by Emptyset | Mirrored (2013) by Silje Nes