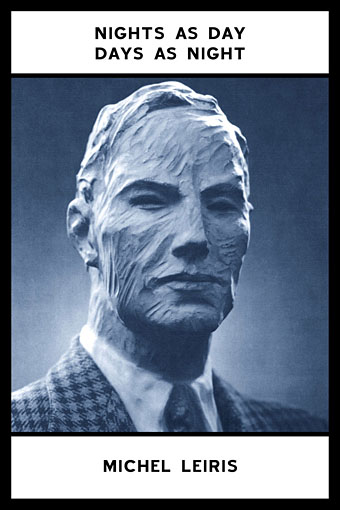

“Le rêve est une seconde vie,” says Gérard de Nerval in the epigraph to the dream journal of Michel Leiris, a collection of oneiric texts published as Nuits sans nuit et quelques jours sans jour in 1961, and which appears this week in a new translation—Nights as Day, Days as Night—from Spurl Editions.

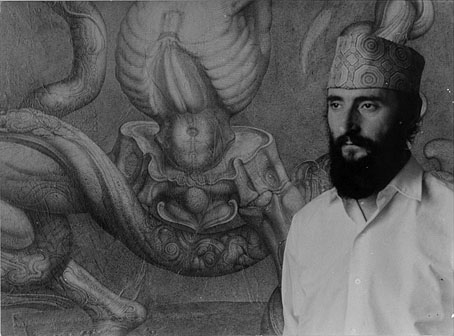

If dreams for Nerval were a second life, for the Surrealists they were a life as important as the waking one, their significance distilled in the declared desire of Max Ernst to keep one eye open on the wake world while the other remained closed and fixed upon the interior. Michel Leiris was a friend of André Masson, and was involved with the Surrealists in the early days until a falling out with André Breton saw him expelled from the “official” ranks. The fatuously doctrinaire Breton seemed to fall out with everyone at some point, and Leiris wasn’t alone in being undeterred by any tinpot Stalinism. Nights as Day, Days as Night is a major Surrealist text, a journal covering the years 1923 to 1960 which may be read as a straightforward transcription of one person’s dream life, or as a series of fragmented narratives, anecdotes and fantasies many of which, in their brevity, operate like condensed fictions. Dreams as raw material for fiction have a long history but are seldom presented en masse in an undiluted form. One problem is that a naked description of a dream is unlikely to be interesting to anyone other than the dreamer unless the description is artfully presented. In his lecture on nightmares, Jorge Luis Borges describes his most terrifying dream—an old Norwegian king appearing at the foot of his bed—which he says was terrifying not because of the appearance of a spectral presence but because of the atmosphere in the room, an atmosphere he found impossible to convey to others.

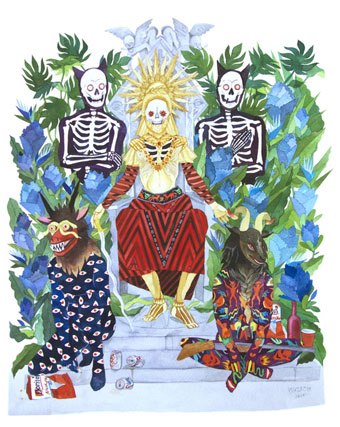

This quality of incommunicability (or a general lack of interest, since “strange dreams” are universal) may be sidestepped if the dreamer is already noteworthy, as with the case of William Burroughs whose My Education: A Book of Dreams is the most obvious equivalent to Leiris’s collection. Burroughs had been mining his dreams for years, however, so the contents of My Education were already very familiar to his readers when the book appeared in 1995. Leiris has the advantage of novelty, and even more than Burroughs he works consciously to make his dreams interesting to a reader. (There’s also some intersection in the Parisian locations; Burroughs included Paris as one of the omnipresent zones in his personal dream landscape.) As with Burroughs, there seem to be occasions when the transcription turns into outright fictioneering. I’ve tried keeping a dream journal myself a few times, and found it difficult to recall anything more than the merest fragments of most dreams. Leiris is selective—many of the entries are separated by several months—but many of his selections run over several pages, and contain detailed descriptions of sequential events. Unless you’re blessed with exceptional recall, some elaboration would seem inevitable given the elusive nature of dreams and their tendency to quickly evaporate in the bleary-eyed morning. From a Surrealist perspective (a non-doctrinaire one, naturally), any subsequent embellishment might be regarded as a literary parallel to the Ernst intention of keeping one eye open while the other remains closed; the dreams become Surrealist texts collaged from Leiris’s dream life and whatever enhancement he applies to the raw transcription. Many of the shorter transcriptions remain faithful to the abrupt disjunctions of the dream state, replete with sudden changes of location, personality and even reversals from subject to object. Literature has the ability to convey these disjunctions much more accurately than other media. Painting, drawing and collage only ever create a single, static image; film has the advantage of movement but, like other visual media, can’t help but make everything seem all too tangible. In film, animation comes the closest to dreams but still lacks the ability to put you inside the consciousness of the dreamer the way that Leiris’s texts do, fictional or otherwise.

Spurl’s Nights as Day, Days as Night is translated by Richard Sieburth, and features a foreword by Maurice Blanchot. Order it here.