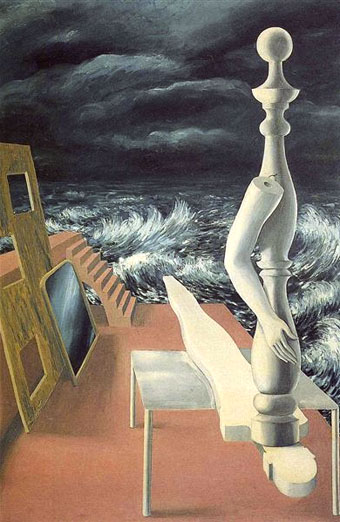

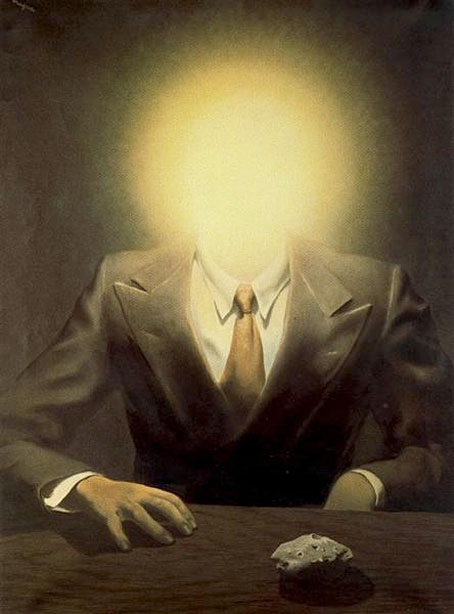

The Pleasure Principle (Portrait of Edward James) (1937) by René Magritte.

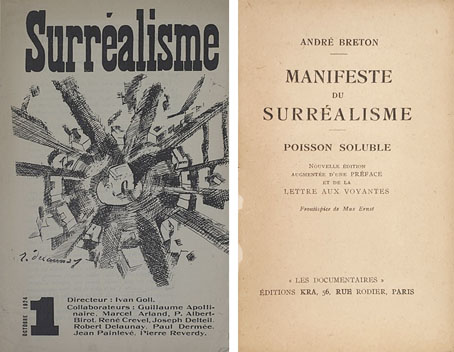

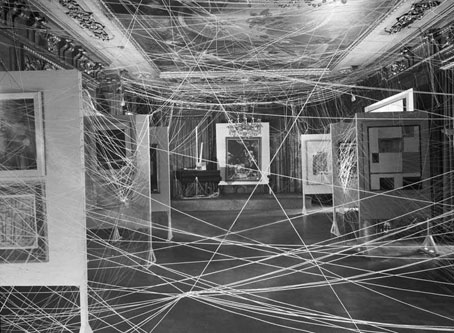

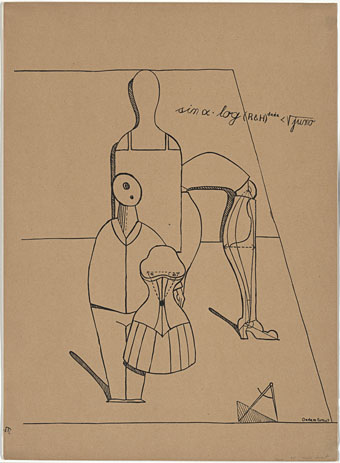

I was reading a book about Surrealism recently that I won’t shame by naming even though it was a bad piece of work: rambling, repetitive and with one section padded out by unfounded speculation. I managed to get a third of the way through before losing my patience when the author began to refer repeatedly to the wealthy British art patron “Edward Jones”. Edward James, as he’s more usually known, is a name guaranteed to turn up eventually in histories of 20th-century Surrealist art; despite not considering himself a collector James managed to amass the largest personal accumulation of Surrealist art in the world. For several years he was a patron of many artists including Dalí, Magritte and Leonora Carrington, becoming a life-long friend of the latter when they both moved to Mexico. He was also the model for some of Magritte’s paintings, including the very influential Reproduction Forbidden. The book that misnamed him was from a major British publisher, one who I usually regard as reliable which makes an error such as this especially annoying.

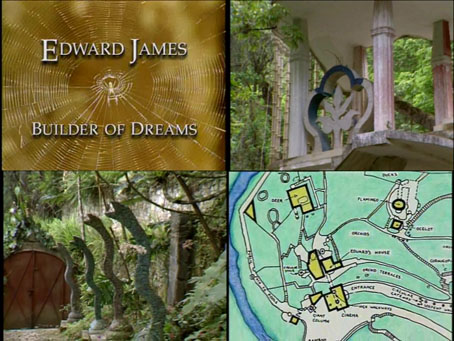

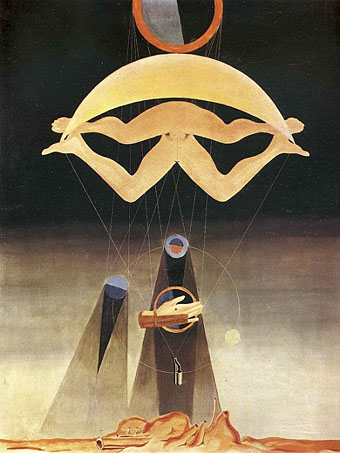

Anyway…much of the history of Edward James’s involvement with the Surrealists is recounted in this hour-long documentary made in 1995 by Avery Danziger and Sarah Stein, a run through James’s charmed life, from gilded youth as an aristocrat and inheritor of vast wealth, to his old age as “Uncle Edward”, a benevolent eccentric living in the Mexican jungle at Xilitla where he spent many years constructing his own work of art, the concrete fantasia known as Las Pozas. Substantial portions of the documentary are lifted from Patrick Boyle’s The Secret Life of Edward James, a TV profile made in 1978 that caught the man at a time when Surrealism in Britain was briefly trendy again thanks to a large retrospective exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London. Danziger and Stein’s film is a kind of supplement to Boyle’s, showing us a more complete Las Pozas while fleshing out the impressions of James via new interviews with his friends and colleagues. Not everyone who gets thanked at the end made the final cut, so there’s no Leonor Fini unfortunately, but Leonora Carrington is present via shots from the Boyle film and extracts from a taped interview.

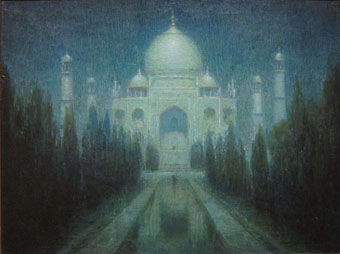

One aspect of Las Pozas that seldom gets mentioned (although I think George Melly might have made the connection) is the degree to which the place fits into the tradition of folly-building by wealthy British aristocrats. Follies are a familiar architectural feature of Britain’s stately homes, and being architectural caprices they come in all shapes and sizes. Most tend to be small one-off constructions, often taking the form of towers or fake ruins. The only folly comparable in scale to Las Pozas is Portmeirion, the pastiche Mediterranean town built by Clough Williams-Ellis on the coast of north Wales. Williams-Ellis, like James, spent decades tinkering with his pet project, and both locations have ended up supporting themselves by offering hotel facilities to tourists. Portmeirion, however, lacks the strangeness of the cement anomalies at Las Pozas; the only thing that’s strange about the place is its departure from vernacular Welsh architecture. Imitation and trompe-l’oeil are common elements among British follies. The closest that Portmeirion came to Surrealism was in the 1960s when it was used as a location for The Prisoner TV series. I imagine James would have found Williams-Ellis’s architectural taste rather too neat and refined. Las Pozas is a wild place that must require continual attention to prevent it from being consumed by the surrounding jungle. One of the houses there is named after Max Ernst (Danziger and Stein interview the owner), and it’s the fantasy jungles in the paintings of Ernst and Henri Rousseau that Las Pozas takes as its model.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealism archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Eco del Universo

• The Secret Life of Edward James

• Palais Idéal panoramas

• Las Pozas panoramas

• Return to Las Pozas

• Las Pozas and Edward James