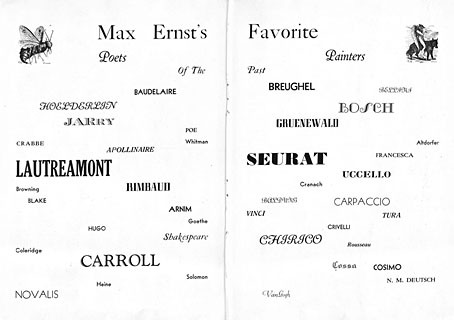

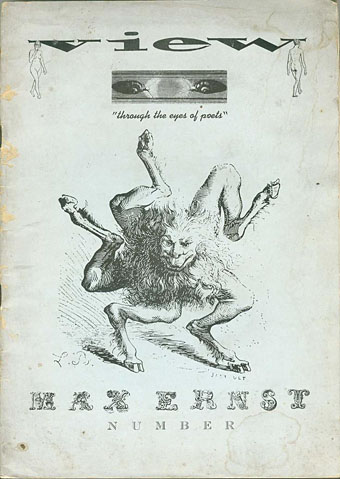

The cover for the Max Ernst number of View magazine (April, 1942) that appears in Charles Henri Ford’s View: Parade of the Avant-Garde was one I didn’t recall seeing before. This was a surprise when I’d spent some time searching for back issues of the magazine. The conjunction of Ernst with Buer, one of the perennially popular demons drawn by Louis Le Breton for De Plancy’s Dictionnaire Infernal, doubles the issue’s cult value in my eyes. I don’t know whether the demon was Ernst’s choice but I’d guess so when many of the De Plancy illustrations resemble the hybrid creatures rampaging through Ernst’s collages. Missing from the Ford book is the spread below which uses more De Plancy demons to decorate lists of the artist’s favourite poets and painters. I’d have preferred a selection of favourite novelists but Ford was a poet himself (he also co-wrote an early gay novel with Parker Tyler, The Young and Evil), and the list is still worth seeing.

Poets: Charles Baudelaire, Friedrich Hölderlin, Alfred Jarry, Edgar Allan Poe, George Crabbe, Guillaume Apollinaire, Walt Whitman, Comte de Lautréamont, Robert Browning, Arthur Rimbaud, William Blake, Achim von Arnim, Victor Hugo, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, William Shakespeare, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lewis Carroll, Novalis, Heinrich Heine, Solomon (presumably the author of the Song of Solomon).

Painters: Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Giovanni Bellini, Hieronymus Bosch, Matthias Grünewald, Albrecht Altdorfer, Georges Seurat, Piero della Francesca, Paolo Uccello, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Hans Baldung, Vittore Carpaccio, Leonardo Da Vinci, Cosimo Tura, Carlo Crivelli, Giorgio de Chirico, Henri Rousseau, Francesco del Cossa, Piero di Cosimo, NM Deutsch (Niklaus Manuel), Vincent van Gogh.

I’ve filled out the names since some of the typography isn’t easy to read. Some of the choices are also uncommon, while one of them—NM Deutsch—is not only a difficult name to search for but the attribution has changed in recent years. The list of poets contains few surprises but it’s good to see that Poe made an impression on Ernst; the choice of painters is less predictable. Bruegel, Bosch and Rousseau are to be expected, and the same goes for the German artists—Grünewald, Baldung—whose work is frequently grotesque or erotic. But I wouldn’t have expected so many names from the Italian Renaissance, and Seurat is a genuine surprise. As for Ernst’s only living contemporary, Giorgio de Chirico, this isn’t a surprise at all but it reinforces de Chirico’s importance. If you removed Picasso from art history de Chirico might be the most influential painter of the 20th century; his Metaphysical works had a huge impact on the Dada generation, writers as well as artists, and also on René Magritte who was never a Dadaist but who lost interest in Futurism when he saw a reproduction of The Song of Love (1914). Picasso’s influence remains rooted in the art world while de Chirico’s disquieting dreams extend their shadows into film and literature, so it’s all the more surprising that this phase of his work was so short lived. But that’s a discussion for another time.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Viewing View

• De Plancy’s Dictionnaire Infernal

• Max Ernst album covers

• Maximiliana oder die widerrechtliche Ausübung der Astronomie

• Max and Dorothea

• Dreams That Money Can Buy

• La femme 100 têtes by Eric Duvivier