Details from Caresses aka The Caress (1896), the most famous painting by Belgian Symbolist Fernand Khnopff which can now be explored in detail at the Google Art Project. Caresses was one of Khnopff’s more enigmatic works although the term is a relative one when it comes to an oeuvre in which enigma is the default position. The combination of a young male, a feline female and the trappings of antiquity suggests Oedipus and the Sphinx although the Sphinx of mythology is a far more threatening presence. Adding to the enigma is the fact that Khnopff’s sister, Marguerite, was his model in most of his paintings which means we can recognise her heavily-jawed features in the male figure as well as the female. The essence of Symbolism for me has always been an atmosphere of unresolved pictorial mystery, a quality which this painting exemplifies.

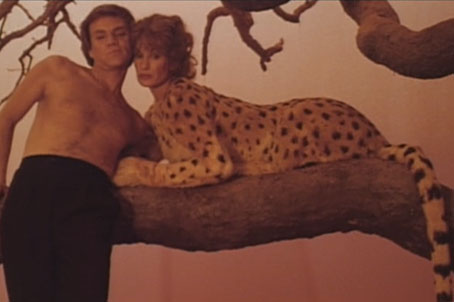

Malcolm McDowell and Ruth Brigitte Tocki in a deleted scene from Cat People (1982).

The mystery would have been carried over to the cinematic world in 1982 if the producers of Cat People had kept their nerve. The “Leopard Tree” dream sequence was to have featured a moment when Irena (Nastassia Kinski) meets her dead brother and mother in a pose which recapitulates Khnopff’s painting. The painting itself also appeared earlier in the film although it’s so long since I watched it I forget now whether that moment was also excised. The dream sequence may have been stretching audience credulity too far but the symbolism is fitting not least for the incestuous nature of the story. Here’s the scene in the final cut set to Giorgio Moroder’s fantastic score.

Daniel Day-Lewis and Michelle Pfeiffer.

The painting definitely did appear on-screen in 1993 where it overshadows a crucial conversation in Martin Scorsese’s adaptation of The Age of Innocence. Given that the setting is New York in the 1870s the usage is slightly anachronistic but once again the symbolism works for a scene which concerns unacceptable and unrequited passions.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Symbolist cinema

• Bruges-la-Morte