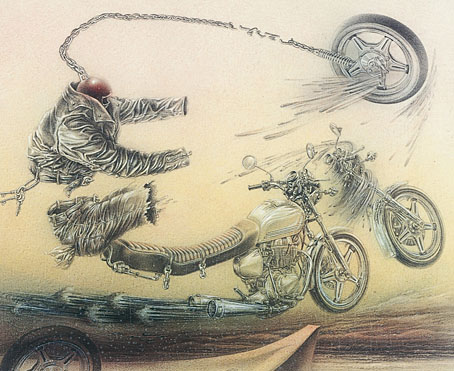

Another painter gone, and a really extraordinary one at that. I wrote something about German artist Sibylle Ruppert two years ago, and only heard about her death this week following an email from Leslie Barany of Barany Artists. Leslie also sent copies of recent exhibition material from a Ruppert show last year at the HR Giger Museum in Gruyeres, Switzerland, from which these pictures have been taken. The picture above gives some idea of the intensely visceral nature of her paintings and drawings. Giger owns (or owned) the picture below as he reproduces it in one of his books, along with other works from his personal collection.

There was an official site for Sibylle Ruppert’s work but, as is often the case with artist sites, it appears to now be defunct. This is frustrating since her work isn’t very visible on the web at all. Anyone interested could start with this set of Flickr views of the Giger Museum exhibition. She was a fantastic artist in all senses of the word.

The following is a note credited to Alain Robbe-Grillet and some biographical details taken from the gallery materials. They’re presented here as printed:

Je m’avance avec un croissant malaise, apprehension peut-etre, avec lenteur en tout cas, dans une sorte de souterrain tres encombre (engorge, meme, en depit de ses dimensions sans doute considerables), que j’imagine bourre de pieges. (J’allais dire pourri…) La lumiere est vive par endroit, sans que l’on puisse deviner d’Oll elle tombe, laissant tout a cote des plages d’ombre dense, et comme visqueuse. Cependant, meme dans les zones bien eclairees, la precision des lignes est suspecte, car on aurait du mal a rattacher ces fragments trop nets, trop dessines (le trace sans bavure d’une pointe aigue), a quelque figure d’ensemble nommement identifiable. L’impression qui domine, au milieu de cette dangereuse incertitude, est qu’il doit y avoir la une grande quantite de chevaux eventres, des etalons a musculatures massives, avec des herses, et des crocs de boucher, et des socs de charrues, avec aussi des femmes nues aux formes splendides, melees au carnage. Je pense a la mort de Sardanapale, evidemment, mais la scene qui m’entoure se situerait plusieurs minutes apres l’instant fragile immobilise par Delacroix, Oll toutes les courbes du desir sont encore rangees aleurs places diurnes. Tandis qu’icl, devant moi, derriere moi, sur ma droite ou sur ma gauche, et presque sous mes pas, ce qui s’offre aux sens revulses ce sont les hontes secretes de l’anatomie : les orifices ecarteles, les entrailles repandues, les secretions, les pertes. Une pointe aigue, ai-je ditQ Oui, le gluant et l’acere semblent, maintenant, s’engendrer en cercle l’un l’autre, le fin couteau du supplice appartenir au meme monstre que la chair ignominieuse qui s’ entaille (se debonde), les sexes s’invertir, insidieusement, et s’invaginer l’arme du crime. Parvenant non sans peine a vaincre mon horreur, ou bien au contraire enfin vaincu par elle, je me decide a toucher… J’approche une paume tendue, doigts ecartes, vers cette substance innomable… Ma surprise est immense : tout cela est en metal poli, sec, luisant mais dur, et froid comme de la glace. Non, je ne suis pas surpris : je le savais deja, bien entendu.

—Alain Robbe-Grillet

Sibylle Ruppert was born during an air raid on September 8th, 1942. It was the night of the first massive bombing of Frankfurt during World War II. With a numbered tag around her neck, Sibylle was, immediately whisked from the maternity ward down to the bomb shelter in the basement, while her mother was moved to safety under a supporting column of the hospital staircase.

She spent her infancy between the nursery and an improvised bomb shelter in which plaster fell from the ceiling whenever the bombs hit the neighborhood. In spring 1944 her parents decided to flee Frankfurt for the countryside. Sibylle’s first memories were of the shoving and screaming crowds on the platform of the train station desperately trying to climb into the overcrowded wagons.

Although the family spent the remainder of the war in relative security, they were subjected to mistreatment and greed at the hands of the farmers who gave them shelter. After the war they were taken in by an aristocratic family who owned a castle and Sibylle spent her early childhood years as if in a dream world. Her father was a graphic designer and young Sibylle spent hours upon hours near his desk watching as he drew. One day she seized his hand and promised him that she would paint nice colourful pictures just like him. Her first drawing surprised everyone, it was a brutal illustration of a fist stricking the middle of a face – she was 6 years old.

At age of 10 she had a religious enlightment and she insisted on becoming a nun. Only the great efforts of her parents managed to dissuade her from taking up a novitiate. In school she was not the best, except in her art classes where she far surpassed all the other students to such an extent that her instructors could not believe that she painted the pictures by herself. Secretly she took the entrance examination of the Städel Akkademie and passed brilliantly.With the support of Prof.Battke she worked relentlessly and created up to 20 drawings a day.

Sitting immobile, continuously, behind the drawing board caused her to gain quite some weight, so her mother enrolled her in the neighborhood ballet school. Sibylle tackled her new activity with the same energy and will-power as she did drawing which prompted the school authorities to give her a choice: either art or dance, but not both at the same time. As soon as she turned 18 she solved the problem her own way by escaping to Paris, the city of her dreams, where she enrolled in a dance school in Clichy. During the day she followed the strict regimen of dance classes, but at night she roamed the notorious streets of Pigalle and Montmartre, fascinated by the ambiguous characters in these neighborhoods.

As she was too tall for classical ballet she joined the famous dance ensemble of Georges Rech. This was the beginning of an adventurous life as a revue dancer touring all over Europe and the Middle East. But while her colleagues relaxed Sibylle visited all the local museums and galleries and continued drawing her every free minute. Then all of a sudden, in New York, she decided to give up on her dancing career. She returned to her family in Frankfurt and started working as a drawing instructor at the art school founded by her father.

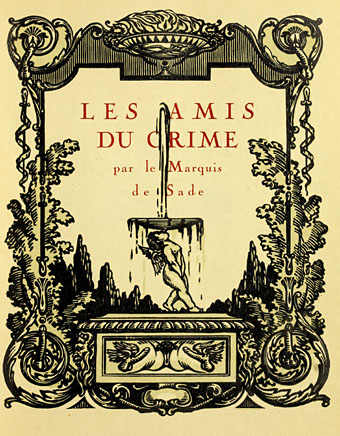

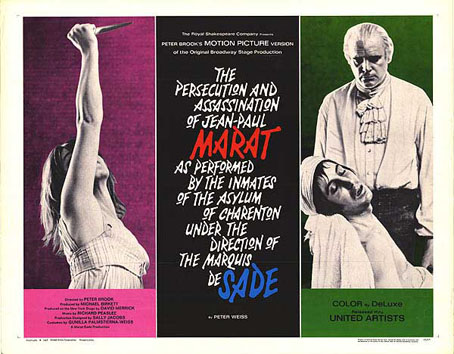

In addition to her teaching, at night she pursued her own personal work, inspired by the „divine“ Marquis de Sade and his frightful universe. Encouraged by notable German intellectuals like Peter Gorsen, Theodor Adorno and Horst Glaser whom she later married her drawings start to become well known. The exhibitions organised by the Sydow – Zirkwitz Gallery in Frankfurt consternated as much the traditional art audience as they produced raised eye brows among the intellectuals.

In 1976 she moves to Paris and exhibits her large format charcoal drawings, inspired by the writings of de Sade, Lautréamont and Georges Bataille, her collages and paintings at the Gallery Bijan Aalam. French intellectuals and great thinkers like Alain Robbe-Grillet, Pierre Restany, Henri Michaux and Gert Schiff show interest and are fascinated by and try to interpret her infernal work. When the gallery closes in 1982 she returns to teaching drawing and painting. She starts giving art classes in prisons, psychiatric institutions and drug rehabilitation centers. Today, Sibylle Ruppert lives a cloistered life, withdrawn from the public, in Paris.