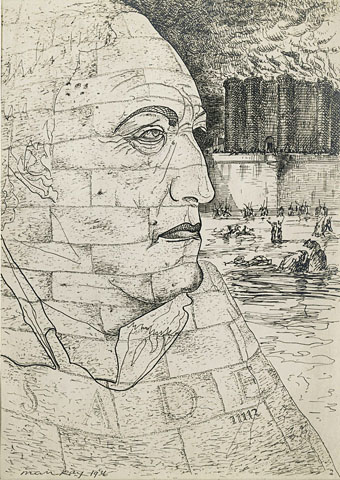

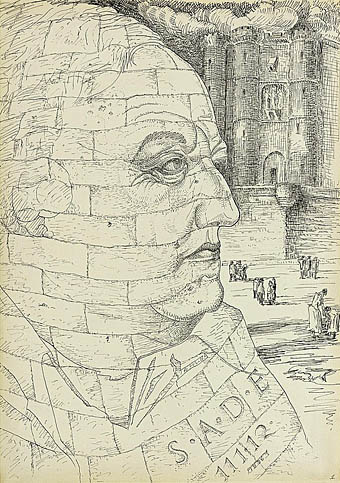

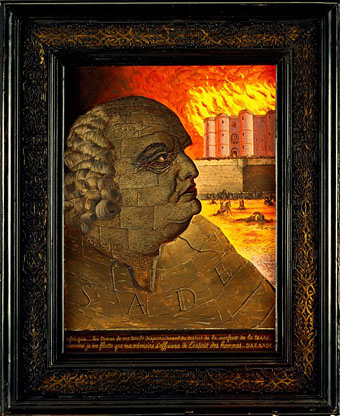

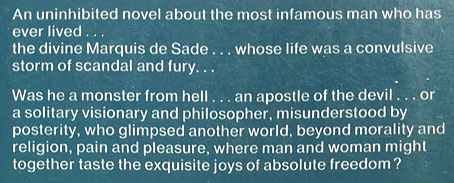

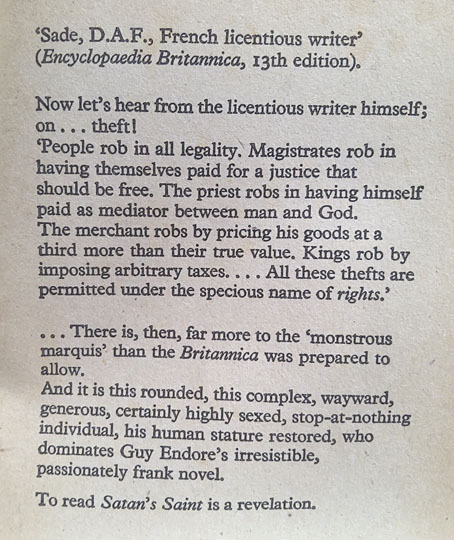

After unearthing this book in July I finally got round to reading it. Guy Endore’s biography of the Marquis de Sade isn’t a great work of literature (and my paperback is also badly typeset) but it was worthwhile for the sketch it offers of the life and philosophies of the notorious libertine. Sade is of interest to me more for his importance to subsequent generations than for his works (although the one leads back to the other), not least the Surrealists who revered him as a revolutionary thinker far ahead of his time. But this interest isn’t really enough to warrant immersion in a major biography which would run to many hundreds of pages, and have to take account of the tumultuous historical era that Sade lived through: pre-Revolutionary France, the Revolution itself, then the Napoleonic period.

Guy Endore was a biographical collagist whose method in this and other books was to explore the life by stitching together with his own commentary extracts from letters and diaries and, where necessary, his own inventions. Most editions of Satan’s Saint proclaim the book as a novel but this isn’t really the case, Endore describes his text in the introductory note as a “novelized Ph.D. thesis”. The note also indicates the passages he was forced to invent when the documentary material was absent. Sade’s life was more turbulent than most, a continual round of family drama, pursuit by the authorities and serial imprisonment, all taking place during a time of the greatest national upheaval, so it’s no surprise that letters, diaries and other documents have been lost. Endore’s most substantial invention is the diary of Sade’s sister-in-law, Anne-Prospère de Launay, with whom the Marquis was besotted, and who he took with him to Italy when he fled his first court conviction and a death sentence. Endore attempts to explain (not always successfully) how the convent-raised woman could not only betray her sister and the rest of her family but also run away with a man accused of terrible sexual crimes. Less invention is required for the Marquis himself since some letters do survive, and his voice and opinions are present throughout his published writings. Given Sade’s enduring reputation it’s a surprise to discover how much of his life was consumed by familial squabbles, especially with his mother-in-law. The Sade family saga, like many of his novels, is a familiar human affair inflated to outrageous proportions; the hatred between Sade and his in-laws was mutual but each saved the other from execution.

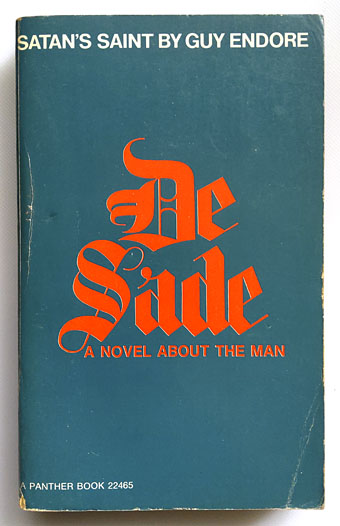

It’s that Rubens typeface again… First US edition, 1965.

Endore’s penultimate chapter steps away from the biography to present a talk given to students at the University of California in May 1962. The lecture allows the author to summarise his attitude to Sade which isn’t so much one of admiration but respect for a man who stood against the hypocrisies of his time even when his life was at stake. “I never killed anyone,” Sade said in later years, and Endore draws a lengthy comparison between Sade and Napoleon Bonaparte, the latter being responsible for the destruction of Sade’s published novels as well as the deaths of hundreds of thousands of men, women and children. The crimes of Napoleon were far greater than those of the man who spent 14 years of his life in prison, yet the name of Napoleon carries none of the notoriety that surrounds the name of Sade. Endore also notes the irony that without his lengthy terms of imprisonment the Marquis might have been as forgotten as he always hoped he would be. Prison compelled him to rage on paper against the world.

I have another Endore book, The Werewolf of Paris, lurking in the unread stacks but it will have to wait. Since reading this piece I’ve had an urge to revisit the novels of Charles Williams. Some metaphysical thrills are in order.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Satan’s Saint

• The Execution of the Testament of the Marquis de Sade by Jean Benoît

• The Marat/Sade