Yes, it’s that magazine again, the perfect thing to feed your head for the new year.

Mark P and SAJ are profiled in the latest Wire.

Ken Hollings rides the world’s subcultural currents mapped by London’s Strange Attractor.

The Wire #275, January 2007

Strange Attractor is well named. There’s really no escaping it. Starting out as a series of live events, it has slowly transmuted into an annual publication, set up an online clearing house for the weird and the wonderful and recently made its first move towards establishing itself as a publishing house. “Strange Attractor celebrates unpopular culture,” runs its mission statement. “We declare war on mediocrity and a pox on the foot soldiers of stupidity. Join us.” Who could possibly resist such a challenge? Sooner or later you have to get involved. (In the interests of full transparency: the writer of this article has taken part in a number of Strange Attractor evenings and is a regular contributor to Strange Attractor Journal.)

With orders for the Strange Attractor publications coming in from all over the world, and mainstream media like The Independent On Sunday praising it for producing “one of the most weirdly beautiful, beautifully weird magazines of the past hundred-odd years” a bigger problem presents itself. How do you celebrate unpopular culture without losing its unpopularity?

“There’s certainly no business plan,” admits Strange Attractor Journal‘s publisher and chief editor, Mark Pilkington. “We’re really making it all up as we go along. I hope that Strange Attractor‘s approach to culture is simultaneously that of the archaeologist, the ethnographer, the anthropologist, the occultist, the showman and the curator.”

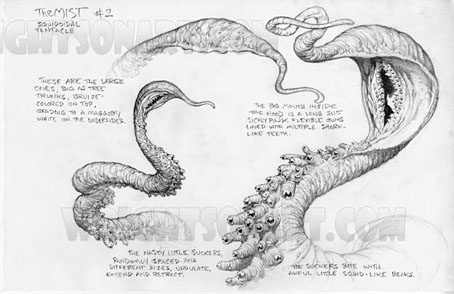

It’s a heady mix. The first two issues, both book-sized anthologies running to more than 200 and 400 pages apiece, have presented material ranged across such elusive topics as mind control experiments, mould art, hair sculpture, cargo cults, neglected gods and forgotten waxworks. Such a list limits more than it clarifies, however. Strange Attractor Journal is concerned less with the unexplained than with the unexpected. You never know what it will cover next.

“I think Strange Attractor is refreshing to people in that it manages to straddle several cultural channels while still following its own agenda,” Pilkington admits, “and it’s one not driven by the same obvious memes. But at the same time it’s important that it doesn’t become obscurantist for its own sake—some things are lost for a reason, others will only resurface when the time is right.”

Strange Attractor‘s wayward eclecticism dates back to a series of monthly events begun in the summer of 2001 by Pilkington in collaboration with artist John Lundberg and continuing over the next two years. Staged at London’s Horse Hospital venue, they gave an early indication of the loose network of experimental enterprises that was starting to come into existence, linking outsider artists with cultural anthropologists, textual hackers and practising occultists.

“We’d mix talks, films, music, presentations, each night being themed around a different topic,” Pilkington recalls. “I rather pretentiously called them ‘information happenings’. Subjects ranged from conspiracy theory to theremins, Esperanto to magick, hoaxes, illusions and psychic deceptions: basically anything that interested us and could draw people that we liked or wanted to meet into one place.” Highlights included a live and bloody demonstration of psychic surgery, sci-fi movie themes played on vintage electronic instruments and a live Lovecraft-influenced Chaos Magick ritual with a soundtrack performed “by a band who couldn’t see what was going on.”

After Lundberg enrolled at the National Film and Television School, Pilkington went solo but eventually grew tired of doing regular live events, deciding instead to do something that would last longer: hence the Journal.

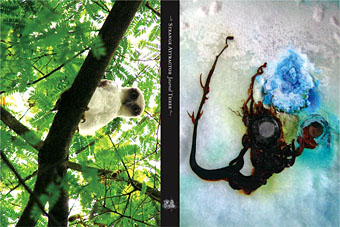

The notion of outliving the moment, of being around for more than just a quick cultural fix, is very much a part of SAJ‘s overall look and feel. The first thing you notice is that the front and back cover of each issue is devoid of text or title, which only appears on the book’s spine. If you want to know who the contributors are, you’ll have to look inside.

“For me, it was about giving as much space as possible to striking images and therefore making them stand out on the bookshelf,” Pilkington explains. “I imagined people being aware that something was wrong with the cover but perhaps not being able to put their finger on it.”

The absence of cover copy also binds together the Journal‘s various contributors in the anonymity of a collective endeavour. “We’re lucky enough to live in an age where we can clearly trace the influences of the past on our present,” Pilkington continues, “and it’s not always today’s most celebrated ideas, musicians and writers who will be remembered. This notion of timelessness is very important to what SAJ is and does. I’d like the books to be as irrelevant to a reader 100 years in the future as it would be to someone 100 years in the past. It’s a re-manipulation of the notion of built-in obsolescence.”

The Journal‘s pages teem with old woodcuts, antiquated typefaces and intricate layouts, giving the impression of having been produced in some parallel past: one that runs counter to established tenets of historical development. Having previously worked as a journalist for periodicals as varied as Fortean Times, Bizarre and The Guardian, Mark Pilkington remains keenly aware of what’s going on around him.

“There’s a particularly vibrant, very loose cultural network in London at the moment,” he remarks, “one that incorporates music and sound, ideas and information, visual arts and almost anything else you’d care to imagine. It’s inevitable that these people, places and events all bounce off and influence each other in a kind of subcultural Brownian motion.”

As well as working closely with designer Alison Hutchinson, readying volume three for publication, Pilkington has also been getting Strange Attractor Press up and running. Its first book to date, The Field Guide: The Art, History And Philosophy Of Crop Circle Making by Rob Irving and John Lundberg, is a particularly cerebral blend of art theory, paranormal phenomena, hoaxes and speculations, ruggedly bound and designed to fit snugly inside your knapsack while out exploring the British countryside. Conventional wisdom says it shouldn’t work, but Strange Attractor‘s own particular blend of parlour magic proves that it does.

“I sometimes see myself as a medium,” Mark reveals, “a channel for all the material that has formed Strange Attractor. I’ve been incredibly lucky with the amazing contributions the Journal has attracted so far.”

There’s no escaping it. Strange Attractor really is well named.

Strange Attractor Journal Three, and The Field Guide: The Art, History And Philosophy Of Crop Circle Making by Rob Irving & John Lundberg, are available now.

www.strangeattractor.co.uk

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Strange Attractor Journal Three

• How to make crop circles

Mark Pilkington has very conveniently saved me the trouble of summing up the wandering history of Dieter Moebius and Hans-Joachim Roedelius in their various incarnations with his introductory piece,

Mark Pilkington has very conveniently saved me the trouble of summing up the wandering history of Dieter Moebius and Hans-Joachim Roedelius in their various incarnations with his introductory piece,