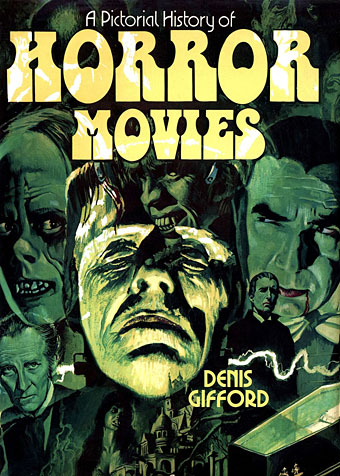

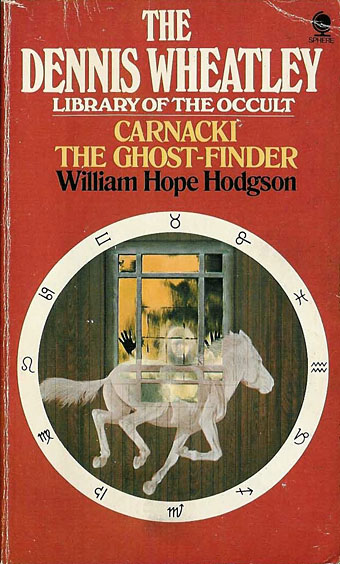

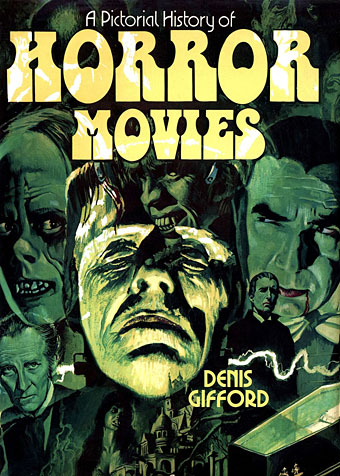

Cover art by Tom Chantrell.

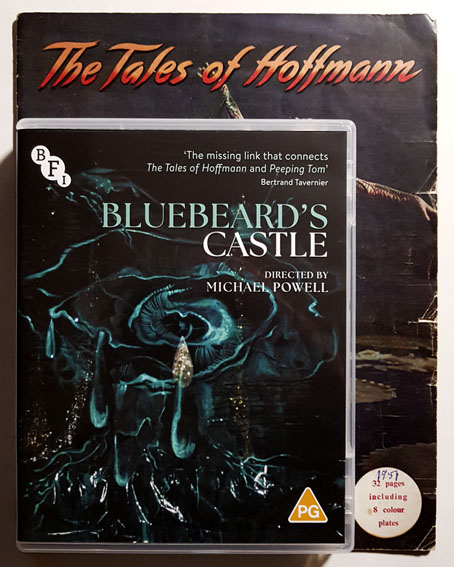

Halloween approaches so here’s a book that suits the season. Denis Gifford’s A Pictorial History of Horror Movies was published in Great Britain by Hamlyn in 1973. A large-format hardback of just over 200 pages, this was a cheap production for wide distribution, and evidently sold well: my edition from 1980 is the 12th reprint, and the book was still in print in 1983, in a slightly longer edition with a new cover.

For a generation of British kids Gifford’s book made an indelible impression, not least because of its ubiquity. It was always easy to find—for years I didn’t have a copy of my own because I invariably seemed to know someone who did—and its mostly black-and-white pictures featured a great deal of imagery that was generally forbidden to those of us under the age of 18. This may seem surprising to Americans, or those in more liberated European countries, but Britain has always had an uneasy relationship with the horror genre despite the legacy of Gothic novels and ghost stories, never mind Dracula, Frankenstein and the rest. Literary manifestations command a grudging acceptance if enough years have passed since first publication but Britain’s moralists and censors have fretted over pictorial horror for decades, especially the film and comic-book variety.

La Belle et la Bête (1946).

Almost all horror films screened in Britain over the past century were for audiences of 18 or over, while horror films on TV were never shown before 10pm. That scene in Halloween (1978) where the kids are watching The Thing From Another World on television in the early evening would have been impossible here. In 1982 we had the start of the “video nasties” panic, a particularly disgraceful episode for those eager to interfere in other people’s entertainment, and an issue that rumbled on for the rest of the decade. As for print media, I still have a leaflet from the late 1980s given to all applicants of UK passports which lists “horror comics” along with weapons, drugs, poisons, etc, among the items forbidden from import into Britain. This climate gave Gifford’s guide an illicit charge it might not have had if published elsewhere: the book delivered a concentrated dose of the forbidden.

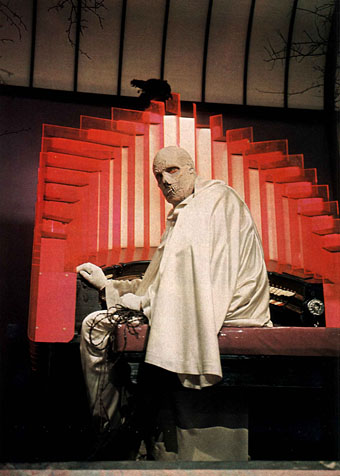

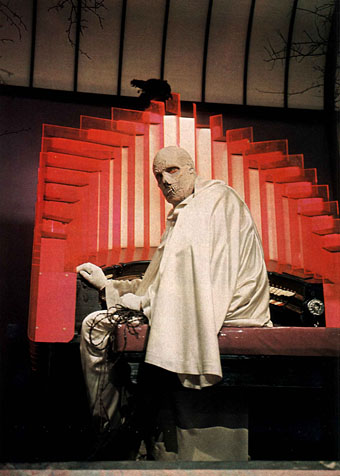

Vincent Price as Doctor Phibes.

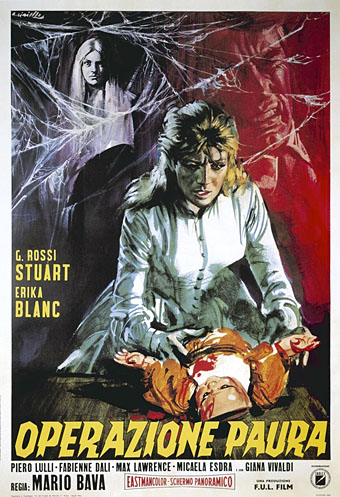

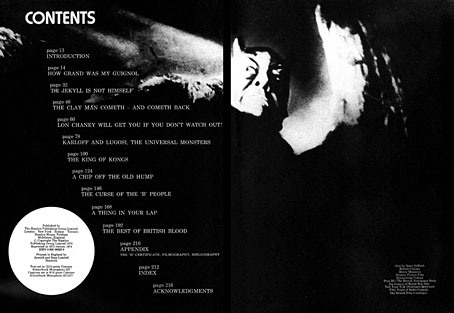

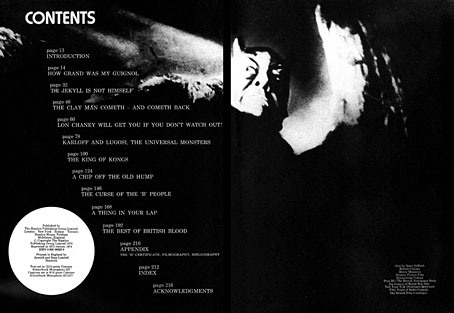

Denis Gifford (1927–2000) was, among other things, a comics artist, a comics and film historian, and a collector of comic books and horror ephemera. Most of the material in A Pictorial History of Horror Movies is from his own collection, and an excellent collection it was. More than 300 stills run through the entire history of horror cinema from the earliest Méliès shorts to German Expressionism, Universal horror, Hammer horror, AIP monster movies, Toho monster movies, and on to the garish efforts of the late 1960s; he even manages to get in a still from Carry On Screaming. The accompanying text is concise but authoritative, although I doubt anyone ever used the book as a serious study. Yet for a 12-year-old this was a perfect introduction to the genre, as well as a dizzying intimation of hundreds of films yet to be seen. In place of the films you had pictures implying entire worlds of mystery and terror, many of which are so good they give very unrealistic expectations of the films from which they originate. Some of the most memorable examples for me have been those which are more atmospheric or eerie than horrific, like the sinister child at the window in Mario Bava’s Operazione Paura (1966) aka Curse of the Dead. (See this post for more about the extended life of Gifford’s still.) But there were also plenty of monsters, grotesque makeup effects and even some gore; a female friend of mine was obsessed with the picture of a blonde and bloodied young woman with an axe buried in her head (see below). Looking at the book today I suspect Gifford’s punning captions may have been a nod to Famous Monsters of Filmland, a magazine with a devoted readership but not a title I ever read myself.

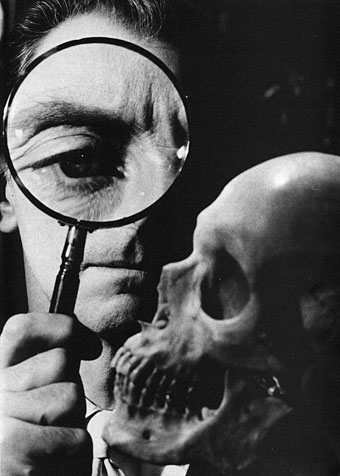

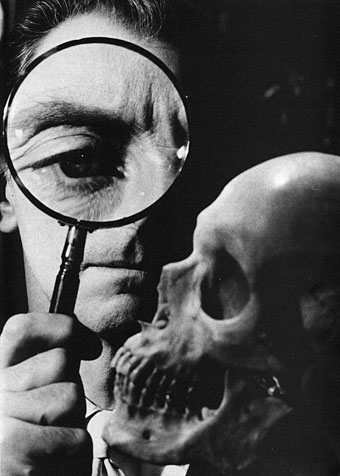

Peter Cushing (The Skull; 1965).

All the pictures here are from an upload of the entire book at the Internet Archive. Gifford isn’t around to complain about this but the book may not remain there for long so enjoy it while you can. A few more pages follow. For an earlier appraisal of the book’s impact on impressionable minds, there’s this piece by Dave Tompkins.

Continue reading “A Pictorial History of Horror Movies by Denis Gifford”