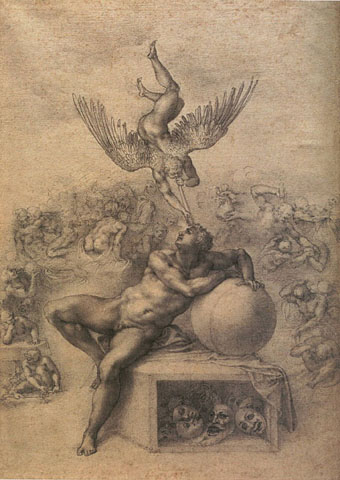

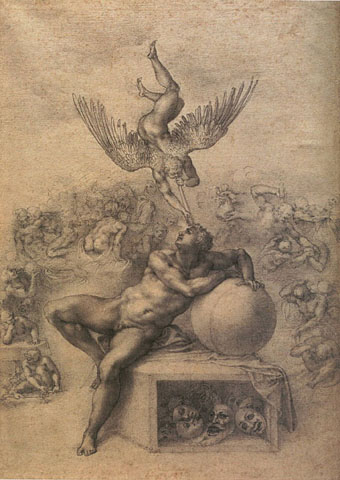

The Dream of Human Life by Michelangelo (1533).

Michelangelo was of course homosexual. That obvious fact still needs restating, simply because generations of art historians have been embarrassed by it. Attempts to deal with the subject have a certain comic interest. E. H. Ramsden, who translated Michelangelo’s letters, refutes the slur of homosexuality with a resounding old-fashioned “Tush!” Anthony Burgess gives an equally Victorian shudder over the David, “so epicene that it invokes unpleasing visions of Michelangelo slavering over male beauty.” Many nineteenth century critics denied him any sexuality at all, apparently preferring a eunuch to a deviant; and even today, it is a common ploy to argue that his genius inhabits some transcendently bisexual—and therefore nonsexual—realm. The evidence for his homosexual loves is too strong to be denied, particularly in the letters to and about one of his models Febo di Poggio, and those about the fifteen-year-old Cecchino de’ Bracci. And it is immediately obvious in his art.

So writes Margaret Walters in The Nude Male: A New Perspective (1978). Appraisals of the great artist’s sexuality have thrown off the prudery in the past thirty years, and a new exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery, London, looks directly at Michelangelo’s attraction to young men. The central work is The Dream of Human Life (or The Dream), one of a number of drawings Michelangelo presented to Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, a Roman nobleman and (we’re told) very handsome youth he met in 1532. No pictures of Cavalieri exist, unfortunately, so we have to take his good looks on trust but it’s unlikely that a 57-year-old artist would have plied a boy with beautiful drawings and hundreds of love poems without good reason. Guardian critic Jonathan Jones has a book about Michelangelo published soon and he writes enthusiastically about the exhibition:

The Courtauld Gallery, that sombre, academic institution, dares to go where Irving Stone never went in his bestselling novel about Michelangelo, The Agony and the Ecstasy. It refutes, with all the authority at its command, centuries of bowdlerisation that have left the nude saints in Michelangelo’s painting The Last Judgment still – in 2010 – emasculated by prudish drapes. It gives us the unmade movie Michelangelo in Love, pouring out his soul in art and verse to a handsome youth whose beauty crystallised all the longings inherent in Michelangelo’s art ever since he carved his teenage masterpiece The Battle of the Centaurs, with its vision of life as a tumult of wrestling male bodies. (More.)

Also on display are previously unexhibited handwritten poems. The Courtauld site has more details about Michelangelo’s Dream which runs from February 18 to May 16, 2010.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The fascinating phallus

• Behold the (naked) man

• Michelangelo revisited