Left: Comets on Fire at the Arthurfest,

Los Angeles, 2005.

Bassoons, flamenco, monks’ cowls…

welcome to the new rock underground

Julian Cope explains why heavy metal, so often maligned, is at the heart of today’s rock avant-garde

Julian Cope

Friday August 18, 2006

The Guardian

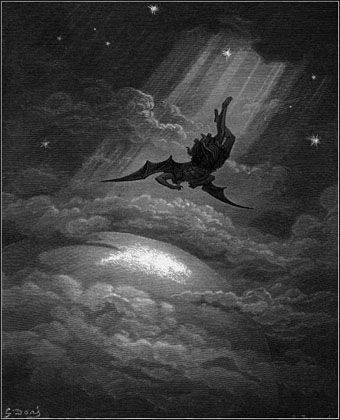

IN APRIL THIS YEAR, after my half-hour stint as a guest vocalist for the US doom metal band SunnO))), I left the stage at Brussels’ Domino festival and removed my burka. Backstage, I remarked to the band’s biographer, Seldon Hunt, how open-minded heavy metallers had become: they were accepting, as festival headliners, a band without a drummer, a bass player or guitars, and with every bearded, long-haired musician among them clad in the habit of a Christian monk. Percipiently, Seldon commented that because the support acts had contained all of those ingredients (except the habits), SunnO))) considered it their duty to reject every metal cliche, replacing each of the archetypal rock instruments with Moog synthesizers, downtuned enough to bring the plaster off the theatre’s ceiling.

SunnO))) are taking metal to places you never imagined. Their music inhabits the territory that once was the preserve of meditative, ambient and experimental music alone. And they are doing it through the most critically reviled music of all. More remarkably, they are not alone. Across the world, underground scenes are using the shell of heavy metal—the volume, the grinding riffs, the imagery, the nomenclature—to test rock’n’roll perceptions and explore boundaries, all the while shamelessly subsuming other vastly different musical styles into their own work.

In a worldwide underground music scene that encompasses artists playing improvisatory music, folk, psychedelic and free jazz, metal is the common thread. You don’t hear much about this music in the mainstream press, especially in Britain, where the kingmakers of the music press have inadvertently created generations of musical whores, all doing their utmost to produce what they think the NME will want, rather than the music they want to make. But why is metal the link? Because the avant-garde musicians in the vanguard of today’s experimental underground scene grew up on it. They spent their late childhoods/early teens playing noisy computer games, watching 24-hour news of the first Gulf war and listening to grunge and metal. As they are mostly in their late 20s and early 30s, their strongest cultural landmarks are the suicide of Kurt Cobain in 1994, and, before it, the overwhelmingly loud sludge of Slayer, Megadeth and Metallica. Therefore the “inner soundtracks” of the new avant gardists are informed by grinding metal bands, just as the sound of the Velvet Underground’s Sister Ray informed that of my own punk generation. Older readers who equate the term heavy metal with the brash, stupefying 1980s anthems of Def Leppard and Bon Jovi will do well to remember that these bands are long out of the equation, having been at their height over 20 years ago.

Continue reading “Maximum heaviosity”