Captain Nemo by Alphonse de Neuville, from Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas (1875) by Jules Verne.

• “…physical remoteness is a category of its own. It is an enhancer: It can make the glorious better and the terrible worse. The oceanic pole of inaccessibility distills physical remoteness on our planet into a pure and absolute form. […] Point Nemo is nearly impossible to get to and offers nothing when you arrive, not even a place to stand. It is the anti-Everest: It beckons because nothing is there.” Cullen Murphy explores the remotest place on Earth. A long and fascinating read, but no mention of Point Nemo’s dreaming tenant.

• More Bumper Book business: Smoky Man has posted the second part of his analysis of the book for (Quasi) (in Italian) which includes some comments from myself about the origin of the Moon and Serpent Magical Alphabet, and why the letter Q in the alphabet is assigned to Cthulhu. Elsewhere, Panini have announced an Italian edition of the Bumper Book for May next year, while at The Beat Steve Baxi reviewed the book from a philosophical perspective.

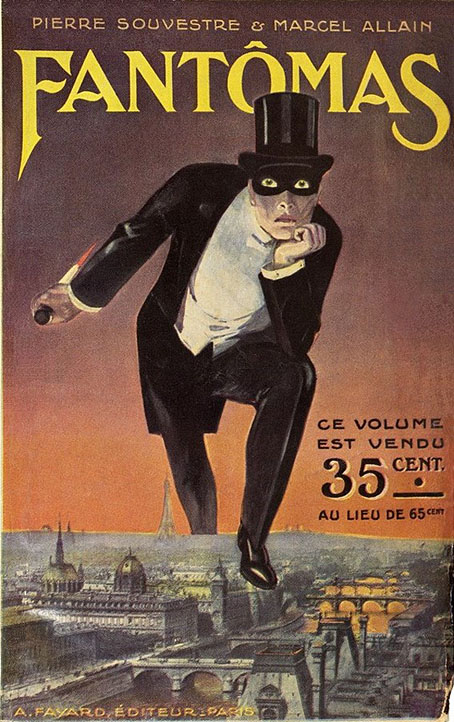

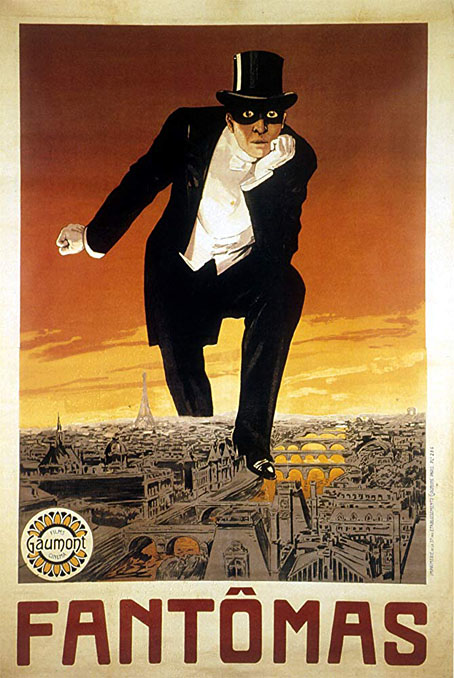

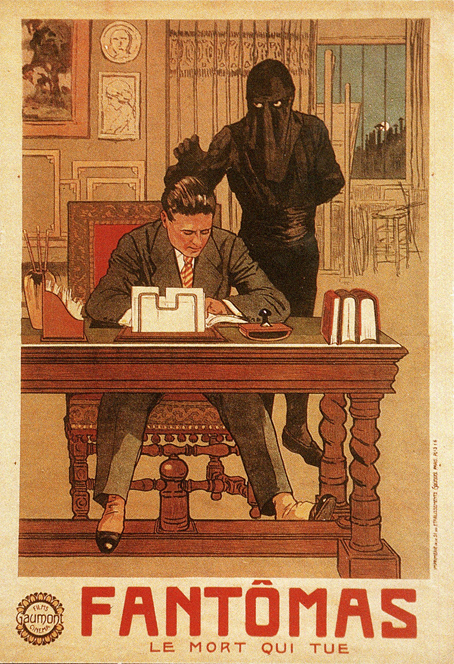

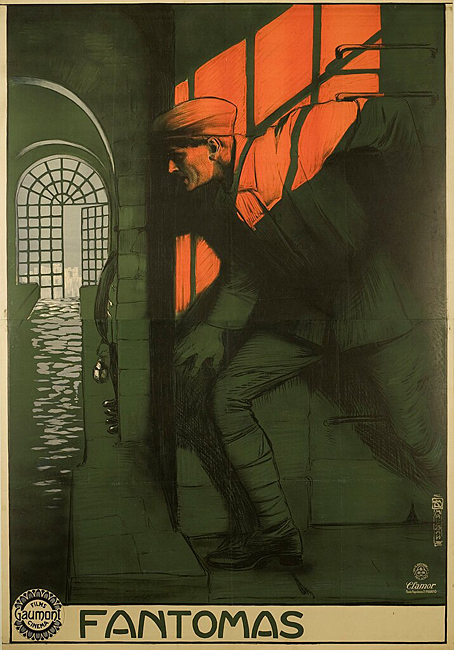

• At the BFI: David Parkinson on where to begin with Louis Feuillade. I’d suggest starting with Fantômas rather than Les Vampires but then I’m biased.

The combination of magic(k)al, ceremonial action, vivid colour and paradoxically serious camp in Jarman’s Super 8 films of the ’70s bears the influence of Kenneth Anger, but the differences between Jarman’s sensibility and Anger’s are more striking than the resemblances. Jarman’s vision is more materialist, austere and hermetic, and less sociological; where Anger identifies the glamour of American popular culture with the Will of the Crowleyan magician, Jarman situates the discovery of the cinematographic mechanism imaginatively within the history of alchemy. Anger cast rock stars as gods and adepts with the intention of harnessing the energy of their recognition; Jarman casts Fire Island, then in its heyday as a gay resort, as a desert defined by sculptural details and occupied by a single masked figure, in scenes that both recall his landscape paintings of the ’60s and ’70s and anticipate the design of his garden at Dungeness.

Luke Aspell on Derek Jarman’s hermetic film/painting, In the Shadow of the Sun

• At Smithsonian Magazine: “Visions of nuclear-powered cars captivated Cold War America, but the technology never really worked”.

• At The Spectator podcast: host Sam Leith talks to Michael Moorcock about 60 years of New Worlds magazine.

• At Public Domain Review: “Light from the Darkness” — Paul Nash’s Genesis (1924).

• At Bandcamp: “Disco godfather Cerrone’s enduring influence on dance music”.

• At Unquiet Things: The Art of Survival: Eyeball Fodder in Dark Times.

• Mix of the week: DreamScenes – November 2024 at Ambientblog.

• New music: The Laugh Is In The Eyes by Julia Holter.

• At The Daily Heller: The College of Collage.

• RIP jazz drummer Roy Haynes.

• Thermonuclear Sweat (1980) by Defunkt | Nuclear Drive (1982) by Hawkwind | Nuclear Substation (2005) by The Advisory Circle