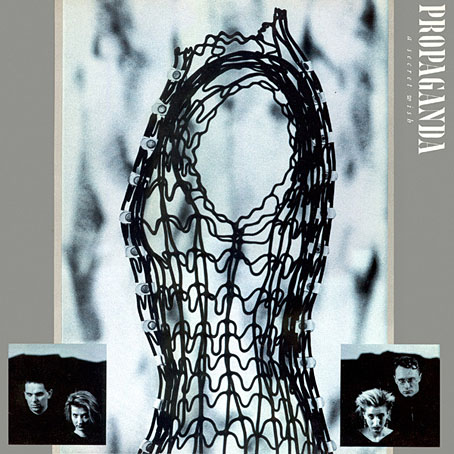

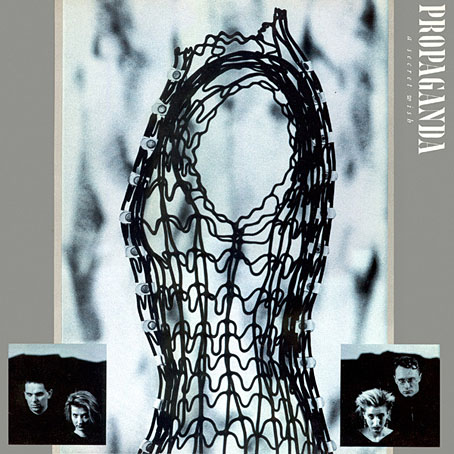

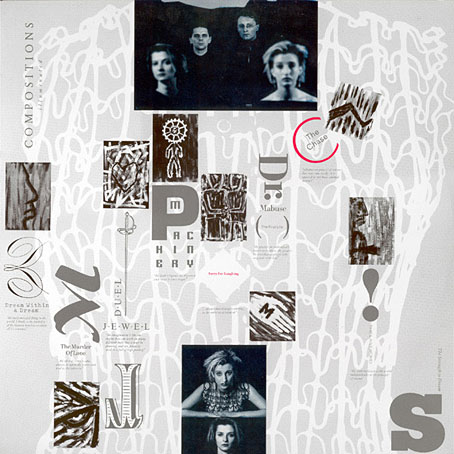

A Secret Wish (1985). Design by the London Design Partnership.

The dark Religions are departed & sweet Science reigns

— William Blake

It’s a hallmark of musical obsession when you find yourself buying the same album over and over. Propaganda’s meisterwerk from 1985, A Secret Wish, was finally released in a definitive double-CD version this week, the fourth edition I’ve bought (after the original vinyl and two other CD releases). This new set is easily the best of the lot.

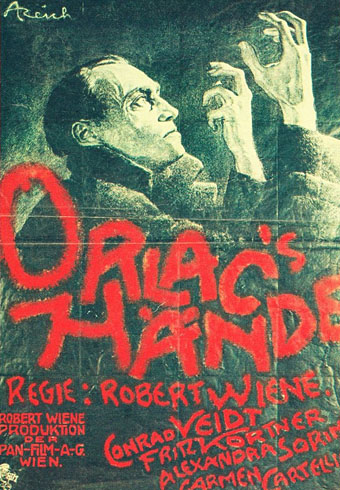

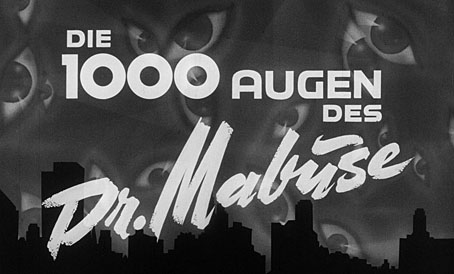

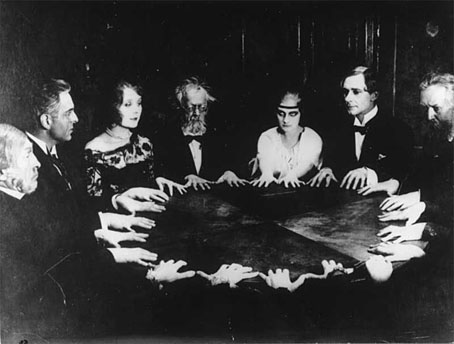

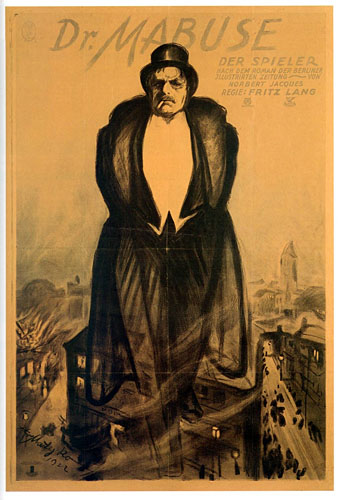

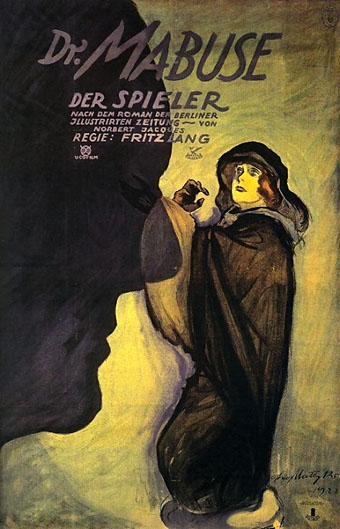

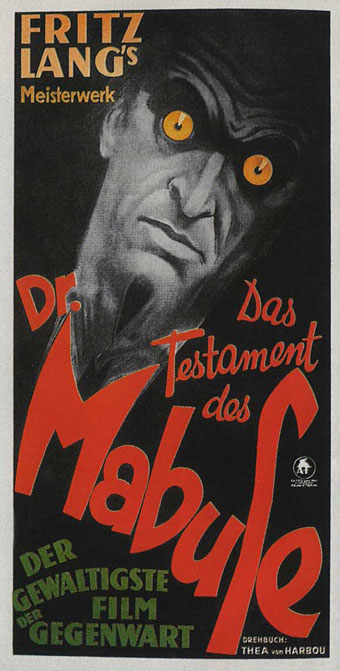

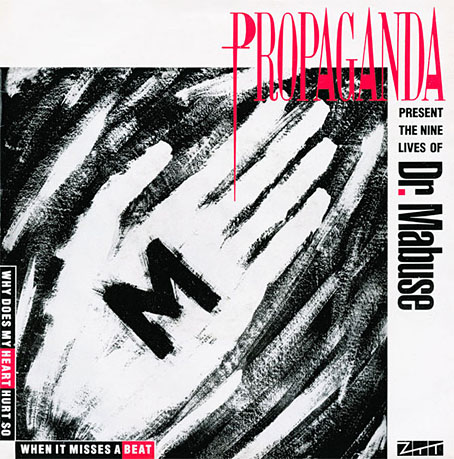

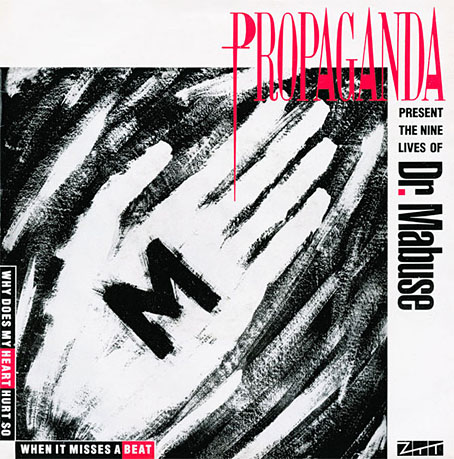

Propaganda were always my favourites among the early acts on Trevor Horn and Paul Morley’s ZTT label; smarter than Frankie Goes To Hollywood and more musical than the Art of Noise. How could I resist another quartet of Germans from Kraftwerk’s home city of Düsseldorf, a group memorably described as “ABBA from Hell”? The first single in 1984, Dr Mabuse, came along when I’d been immersed in Lotte Eisner’s celebrated study of German Expressionist cinema, The Haunted Screen; an avant-garde pop outfit devoted to the same material was just the thing I wanted to hear. Almost a mini-album, the single’s A-side was filled by an epic ten-minute song describing the nature of Dr Mabuse, a villainous anti-hero from several Fritz Lang films. On the B-side there was a cover of The Velvet Underground’s Femme Fatale (and another Lang reference in the subtitle, The Woman with the Orchid) followed by some metal bashing and a taste of the A-side’s Schönberg-esque orchestral stabs before Dr Mabuse returned again at the end. Cover versions were an important thing at ZTT, as was the idea of the 12-inch single as a self-contained work, Mabuse being a prime example. All of this came packaged in a sleeve whose Anton Corbijn painting referenced another Fritz Lang film, M… It felt as though they were doing this purely for my benefit.

Dr Mabuse (1984). Design by Anton Corbijn and XL.

The intertextual reference on this and subsequent releases isn’t surprising given the people involved. Paul Morley took a great delight in embellishing the ZTT releases with quotations—the Frankie album was probably the first chart-topping release with a recommended reading list—while band member Ralph Dörper had been with the Neue Deutsche Welle group Die Krupps prior to Propaganda, and it was his influence which gave them the abrasive industrial edge that I found so attractive. While between groups he released an experimental EP in 1983 under his own name featuring versions of In Heaven from Eraserhead and John Carpenter’s theme from Assault on Precinct 13, and it was Dörper who chose Throbbing Gristle’s Discipline as the demo song which the group used to catch the attention of ZTT. That particular cover version never made it to A Secret Wish although they did perform it live on The Tube, and a later version appeared on the remix album, Wishful Thinking. This recording is happily included on the second disc of the new reissue.

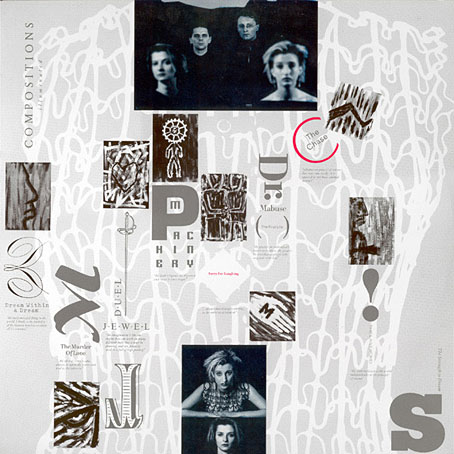

A Secret Wish was released in 1985 and pushed further buttons of obsession for me with the opening track, Dream Within A Dream, which is Edgar Allan Poe’s poem set to music. The album artwork came liberally decorated with Morley’s signifying quotes, the one for the Poe track being the opening lines from HP Lovecraft’s The Call of Cthulhu. Yes, they really were doing this for my benefit… Two further 12-inch singles appeared: Duel/Jewel was the same song presented in an “ABBA” version and a “from Hell” version: sweet and melodic versus harsh and industrial.

A Secret Wish inner sleeve.

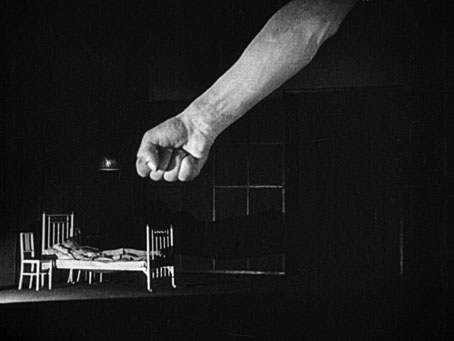

The third and final single, p:Machinery, expanded the short mix from the album into another 9-minute epic whose vision of a population enslaved to industrial technology easily invokes Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, so much so that I used to play the single while running taped scenes from the film on TV. The enormous “Polish” mix of this song has always been scarce on CD, with a Japanese release in 1988, and a later reissue (with some shoddy and superfluous remixes) in 1995. Another benefit of the new edition of the album is that the extended mix provides the climax of the second disc and sounds even more enormous, its brass fanfares accurately described in a review at the time as conjuring images of cities rising from the sea.

Also present for the first time on the new CD is Do Well, the 20-minute Duel suite which was a cassette-only release, plus a number of other previously unavailable mixes. If you have this double-disc set and the Outside World single collection from 2002 then you’ll own pretty much everything that’s great about Propaganda. A lot of pop music from the 1980s sounds horribly dated now: tinny synths, empty production and a paucity of ambition. Propaganda sound as thunderingly magnificent as they did in 1985, and still unique. It’s a shame that A Secret Wish was their finest moment, things fell apart fairly soon after. But one masterpiece will always be worth fifty Duran Duran travesties.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The album covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Metropolis posters