Ask anyone for a definition of this term and most people would immediately mention Leonardo Da Vinci (can his reputation survive Dan Brown?) or Michelangelo, the two most highly-regarded geniuses of the Italian Renaissance. While Leonardo’s numerous achievments are well-documented, Michelangelo’s work as a painter and sculptor tends to overshadow his other talents as an architect (most notably for the dome of St. Peter’s basilica in Rome) and writer of over three hundred homoerotic sonnets and madrigals dedicated to Tommaso dei Cavalieri.

A lesser known figure of the period who perhaps exemplifies the full range of the polymathic Renaissance ideal is Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472). In an era over-stuffed with geniuses, Alberti tends to be overlooked but his achievements in a variety of fields still seem staggering today.

One of Alberti’s earliest works was Philodoxeus (‘Lover of Glory’, 1424), written when he was 20, a Latin comedy that was convincing enough as a parody of Classical style to pass for an original work of the Roman era. Other works followed, among them De commodis litterarum atque incommodis (‘On the Advantages and Disadvantages of Literary Studies’, 1429), Intercoenales (‘Table Talk’, ca. 1429), Della famiglia (‘On the Family’, begun 1432), Vita S. Potiti (‘Life of St. Potitus’, 1433), De iure (‘On Law’, 1437), Theogenius (‘The Origin of the Gods’, ca. 1440), Profugorium ab aerumna (‘Refuge from Mental Anguish’, 1442-43), Momus (another Classical comedy, 1450) and De Iciarchia (‘On the Prince’, 1468). More significant than all of these was Della Pittura from 1436, the first ever study of perspective construction. Alberti’s friend Filippo Brunelleschi had earlier devised his own system of perspective but Alberti was the first to set the principles in book form for other artists.

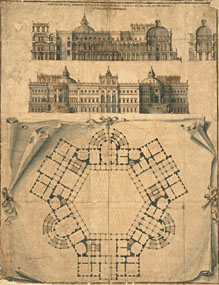

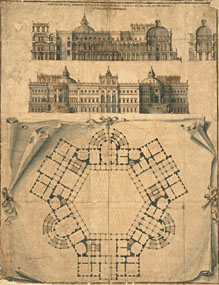

Brunelleschi was an architect and Alberti also produced his own architectural designs, including the Rucellai Palace in Florence, the first Renaissance building using a system of Classical pilasters, and the facade of the Santa Maria Novella church. His monumental study De re aedificatoria (‘On the Art of Building’) was begun in 1450 and occupied him for the rest of his life, a ten-volume work and the first of its kind to address modern architecture based on Classical principles. This was also the first work of architecture to be printed in 1485 and remained an essential working text up to the 18th century. The book’s recommendations for fortification and siege defence were in use for hundreds of years.

Alberti’s restless talents also encompassed music (he was an accomplished organist), map-making and cryptography. The polyalphabetic cypher he created in 1467 was the first significant cypher of its kind since Julius Caesar’s and has since earned him the title “Father of Western Cryptography.” Alberti has also been proposed as the author of the enigmatic Hypnerotomachia Poliphili of 1499. The jury is still out on this but this is a book whose creation would certainly require someone of Alberti’s breadth of knowledge.

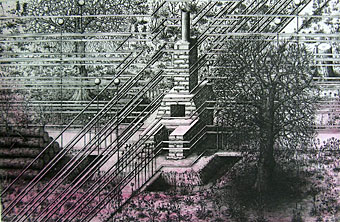

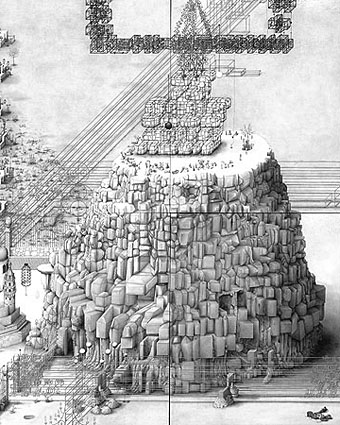

The Renaissance ideal rather fell out of favour in the 20th century, even though there were more than enough polymaths to go around (Harry Smith comes to mind). No one in Quattrocento Italy would accuse any of the great men of the period of being a “jack of all trades, master of none”, the familiar dismissal of a culture that makes a virtue of aiming low. Artists today have to compete in an art market saturated with mediocre work which means they need to find a single gimmick that distinguishes them from the crowd then plug it for all it’s worth. As Robert Hughes memorably says in The Shock of the New, “More artists came out of American art schools in a single year in the 1980s than there were people living in Florence during the Renaissance.” Artists like Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp and Tom Phillips let their curiosity and creativity carry them forward, producing work that ranges over a variety of styles and media. Phillips is a good example of the contemporary Renaissance man, a painter, sculptor, writer, composer and creator of the extraordinary artwork/experimental novel A Humument. The fact that most people are unfamiliar with his name says more about our world than it does about the value of Phillips’ work. Robert Heinlein isn’t a writer I usually have much time for but he had the perfect riposte to this situation, and to the philistine assertion of “jack of all trades, master of none”. “Specialisation,” Heinlein said, “is for insects.”