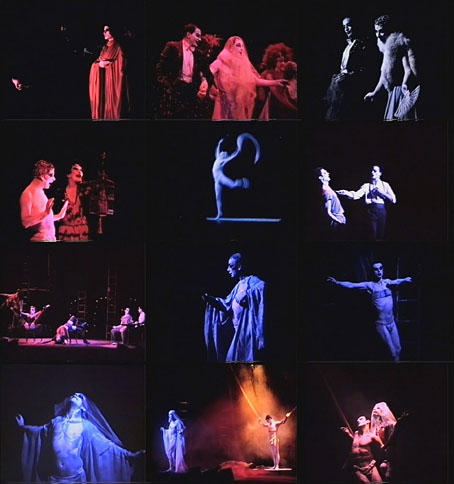

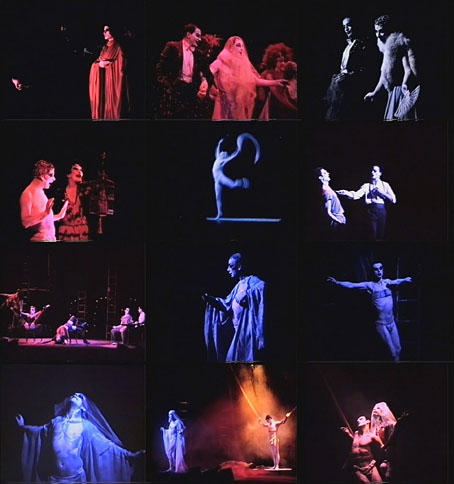

Flowers (1986) by the Lindsay Kemp Company. Photos by Maya Cusell.

Weidmann appeared before you in a five o’clock edition, his head swathed in white bands, a nun and yet a wounded pilot fallen into the rye one September day like the day when the world came to know the name of Our Lady of the Flowers. His handsome face, multiplied by the presses, swept down upon Paris and all of France, to the depths of the most out-of-the-way villages, in castles and cabins, revealing to the mirthless bourgeois that their daily lives are grazed by enchanting murderers, cunningly elevated to their sleep, which they will cross by some back stairway that has abetted them by not creaking. Beneath his picture burst the dawn of his crimes: murder one, murder two, murder three, up to six, bespeaking his secret glory and preparing his future glory.

A little earlier, the Negro Angel Sun had killed his mistress.

A little later, the soldier Maurice Pilorge killed his lover, Escudero, to rob him of something under a thousand francs, then, for his twentieth birthday, they cut off his head while, you will recall, he thumbed his nose at the enraged executioner.

Finally, a young ensign, still a child, committed treason for treason’s sake: he was shot. And it is in honour of their crimes that I am writing my book.

(Our Lady of the Flowers by Jean Genet. Translation by Bernard Frechtman, 1963)

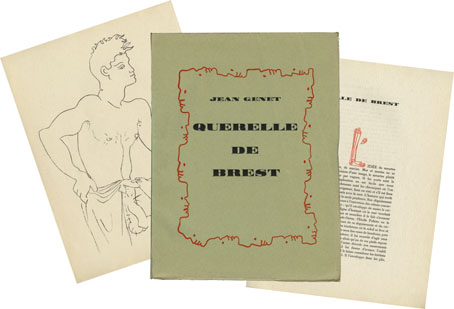

Lindsay Kemp’s all-male version of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé has been the subject of several earlier posts, a production staged in the mid-70s with Kemp himself playing the part of Wilde’s femme fatale. Kemp’s company produced a related work in 1974, Flowers: A Pantomime for Jean Genet, a stage adaptation of Genet’s first novel, Our Lady of the Flowers (1942), in which Kemp played the part of drag queen Divine. Wilde and Genet aren’t so far removed from each other artistically although I can’t imagine them getting on in person. Both men were prisoners, of course, and Our Lady of the Flowers was famously written in prison, the first copy being discovered by a warder and destroyed. There’s a more direct connection in Fassbinder’s Querelle during the scenes where Lysiane (Jeanne Moreau) sings “Each man kills the thing he loves”, the most famous line from Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol which refers to (among other things) one of Genet’s obsessions: the prisoner condemned to death. Wilde would no doubt appreciate Genet’s poetic reimagining of his fellow prisoners, and his use of flowers as symbols; what Genet would have made of Lindsay Kemp’s typically extravagant and rather camp stage creation is anyone’s guess. He did write several plays but in later years evaded questions about them or his novels by claiming to have forgotten all his works. By the 1970s Genet was much more interested in the political struggles of the Black Panthers and the Palestinians.

Much as I like Wilde’s play, given the choice I think I’d prefer to see the Genet staging. Salomé is familiar enough from various stage and film adaptations whereas Flowers was unique. There is a video record of the latter from 1982 but the copy uploaded by Lindsay Kemp has had its soundtrack removed following the usual annoying copyright complaints about the music. So there’s the frustrating choice of watching the whole thing with no sound or watching this 28-minute video compilation of still photos by Maya Cusell from a 1986 performance with music that may be the original live score. One thing the photos show is how close in appearance is Kemp’s Divine to his dancer at the beginning of Derek Jarman’s Sebastiane (1976). In 2012 Kemp talked to Paul Gallagher about his film and stage career, Flowers included.

Update: As noted by radioShirley below, there is a copy of the 1982 performance with full soundtrack!

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Querelle de Brest

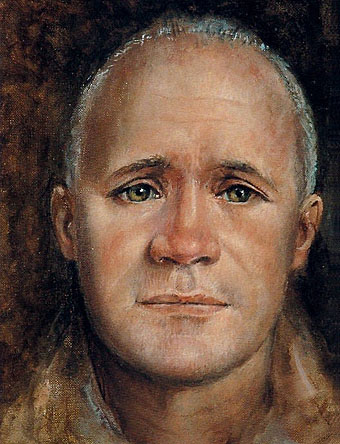

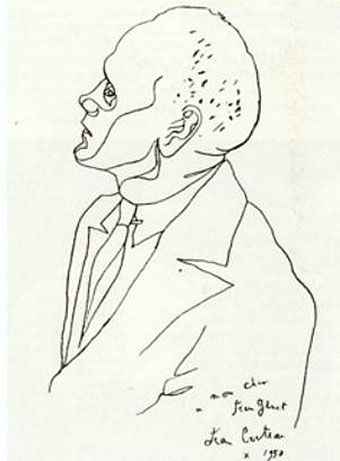

• Jean Genet, 1981

• Un Chant d’Amour (nouveau)

• Jean Genet… ‘The Courtesy of Objects’

• Querelle again

• Saint Genet

• Emil Cadoo

• Exterface

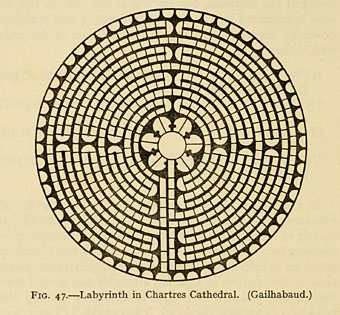

• Penguin Labyrinths and the Thief’s Journal

• Un Chant D’Amour by Jean Genet