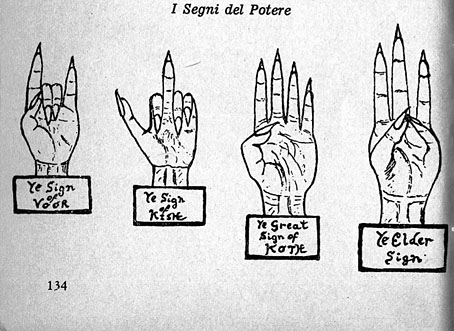

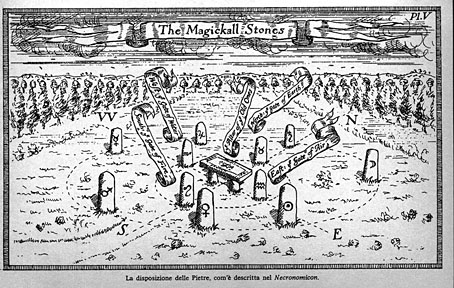

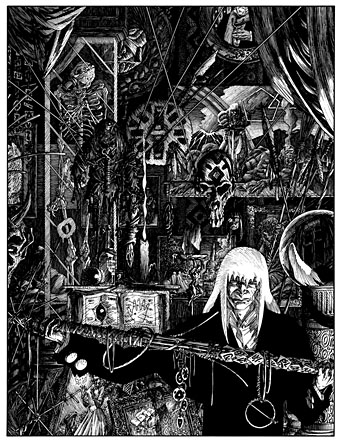

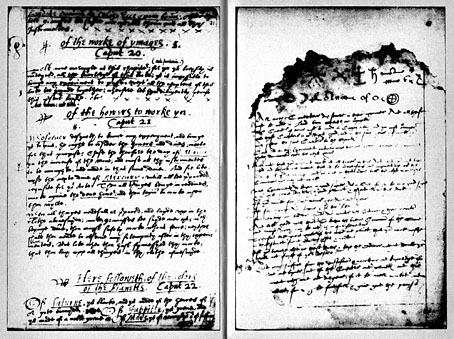

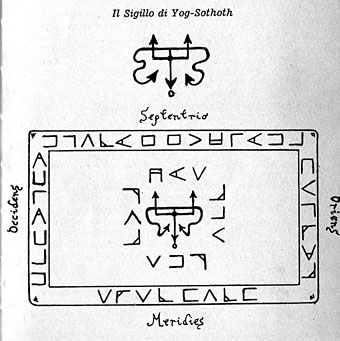

The 1978 edition of the Necronomicon edited by George Hay remains my favourite among the many fake Necronomica. It was the first one I bought, following a memorable “WTF?!” encounter with the Corgi paperback in WH Smiths, and as a book it’s always been better value than the much more popular “Simon” Necronomicon (1977) despite having a smaller page-count. Hay’s book is as much a general guide to Lovecraft’s fiction as an invented grimoire. In addition to the detailed occult fabulation crafted by Robert Turner and David Langford there’s a lengthy introductory essay by Colin Wilson, while the appendices comprise essays by L. Sprague de Camp (“Young Man Lovecraft”), Christopher Frayling (“Dreams of Dead Names: The Scholarship of Sleep”) and Angela Carter (“Lovecraft and Landscape”). The “Simon” book had little in the way of illustration beyond the few invented sigils which you now see reproduced endlessly in role-playing circles. The Hay book, on the other hand, featured a handful of illustrations by Gavin Stamp (all but one of them them credited to the fictitious “GM Sinclair”) which have been marooned with the essays in obscurity for far too long.

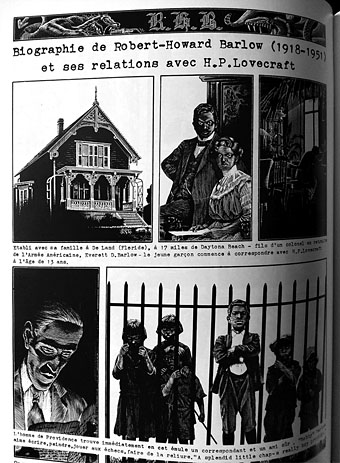

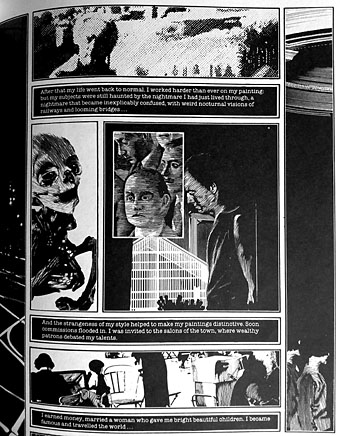

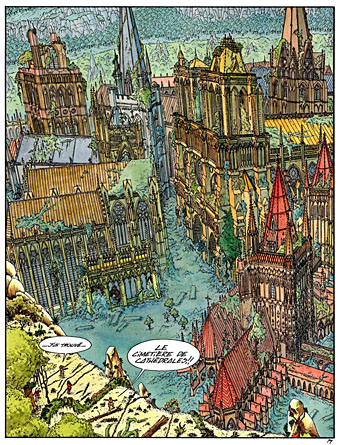

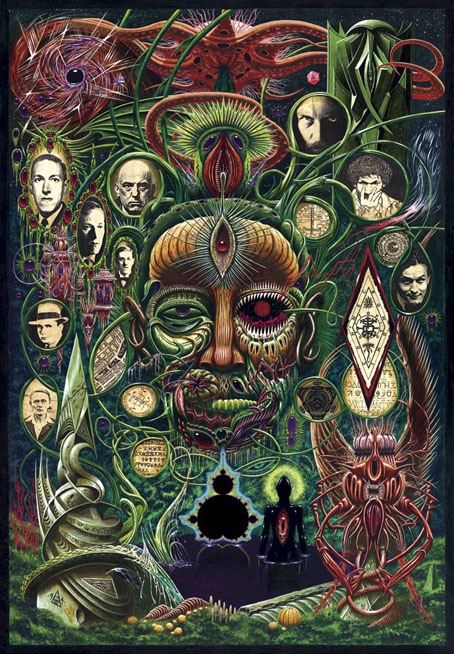

I posted some of Stamp’s illustrations several years ago but they’re worth visiting again now that an Italian translation of the Hay book has turned up at the Internet Archive. This edition, published in 1979 by Fanucci Editore, includes an additional appendix containing two more text pieces plus a portfolio section with further illustrations by Italian artists. The Italians seem to like Lovecraft’s fiction almost as much as the French do. The first substantial collection of Lovecraftian comic strips and illustrations was an Italian book, The Cosmical Horror of HP Lovecraft, published by Glittering Images in 1991. A more recent collection, Lovecraft Black and White from Dagon Press, featured a quantity of illustrations rather like those at the end of the Italian Necronomicon. The Dagon Press collection also reprinted one of my pieces but I don’t seem to have noted this until now.

The cover art for the Italian Necronomicon is worth mentioning since this isn’t a recent piece of art at all. The image is one of eleven woodcuts by Lorenz Stöer (c.1537–c.1621) which were published in book form as Geometria et Perspectiva in 1567. Happily, the 2009 BibliOdyssey post about Herr Stöer and his remarkable works is still available, so you can see the whole series and read about their history without my having to go searching for the details. Stöer’s creations are a good match for Lovecraft’s concept of deranged or non-human architecture. They remind me of Fred Chappell’s Remnants, one of the stories in Lovecraft’s Monsters, in which the Great Old Ones return to the Earth and begin to refashion the planet to their own designs.