This is science fiction.

Presenting the list I mentioned earlier in which I highlight a number of worthwhile science-fiction films (also some TV productions) that aren’t the usual Hollywood fare. I’ve spent the past few years watching many of these while searching for more. This isn’t a definitive collection, and it isn’t filled with favourites; I’ve deliberately omitted a number of popular films that would count as such. It’s more a map of my generic tastes, and an answer to a question that isn’t always spoken aloud in discussions I’ve had about SF films but which remains implicit: “Okay, if you dislike all this stuff then what do you like?” I tend to like marginal things, hybrids, edge cases, the tangential, the unusual and the experimental. And for the past two decades I’ve increasingly come to value anything that isn’t a Hollywood product. There are two Hollywood productions on this list but neither of them were very successful. Not everything here has been overlooked or neglected but many of the entries have, either because they made a poor showing at the box office or because they have the effrontery to be filmed in languages other than English. Not everything is in the first rank, either, but they’re all worth seeing if you can find them.

Liquid Sky.

The starting point is around 1960 because prior to this date any marginal or unusual examples of SF cinema are harder to find. A genre has to be somewhat set in its ways before radically different artistic approaches emerge, and pre-1960 there wasn’t much testing of the SF boundaries in the film world. Science-fiction cinema has also tended to lag behind the written word, so even though the literature was growing more sophisticated during the 1950s, films from the same period are mostly filled with monsters, spaceships and mad scientists. By the 1960s enough written science fiction was playing with (or ignoring) genre stereotypes for a “New Wave” to be identified. Some of the films detailed here might be regarded as cinematic equivalents of SF’s New Wave but I’ll leave it to others to argue the finer points of definition. A few of the choices are a result of directors going in unexpected directions, with several selections being one-off genre excursions by people better known for other things. I’ve omitted many films and/or directors that receive persistent attention, so there’s no David Cronenberg, Nicolas Roeg, Andrei Tarkovsky or John Carpenter; and no Mad Max 2, Akira, Ghost in the Shell or The Prisoner. A couple of edge cases are so slight I couldn’t really justify their inclusion so you’ll have to look elsewhere for appraisals of The Unknown Man of Shandigor (a spy satire with Alphaville influences) and Trouble in Mind (more of a neo-noir fantasy). 2010 is the cut-off point. I’ve never been someone who watches all the latest things so it often takes me years to catch up with recent releases.

Avalon.

I can imagine there might be questions about the availability of some of these films. All I can say is search around. I’ve managed to accumulate half the things on this list on either DVD or blu-ray so they’re not all impossible to find. I did consider posting links but the whole issue of region coding complicates matters. Most of the short films circulate on YouTube, as do a number of the features although these don’t always include subtitles. Have I missed something good? (Don’t say Zardoz….) The comments are open.

Invention for Destruction (Czechoslovakia, 1958)

An evil millionaire named Artigas plans to use a super-explosive device to conquer the world from his headquarters inside an enormous volcano.

(Previously.) It seems fitting to start with a film that adapts a novel by one of the founders of the genre, Jules Verne. Karel Zeman’s third feature extended his technical effects to combine live-action with animation, creating a film in which the engraved illustrations of Verne’s novels are brought to life. With music by Zdenek Liska.

La Jetée (France, 1962)

The story of a man forced to explore his memories in the wake of World War III’s devastation, told through still images.

Chris Marker’s haunting short is one of the great time-travel stories, a 25-minute film that JG Ballard often listed as a favourite. Memory was a recurrent theme in Marker’s work, and memories here provide a physical route into the past, with the predicament of the unnamed protagonist concentrated on a single memory from his childhood. Marker’s interests ranged widely but he haunts the margins of science-fiction cinema in France, assisting Walerian Borowczyk with an early animation, Les Astronauts (1959), as well as the Pierre Kast entry below.

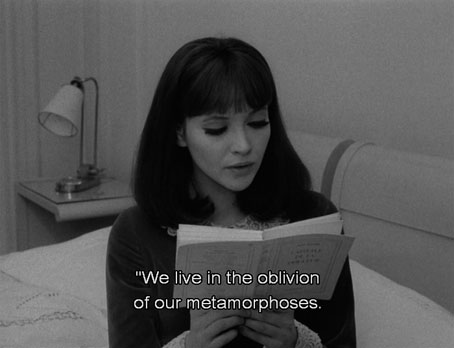

Alphaville: A Strange Adventure of Lemmy Caution (France, 1965)

A secret agent is sent to the distant space city of Alphaville where he must find a missing person and free the city from its tyrannical ruler.

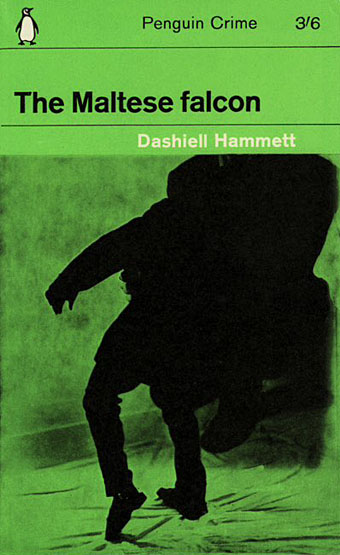

Another Ballard favourite, and not a neglected film by any means but the first in our collection of one-off SF excursions by directors better-known for other things. Alphaville is also important for being the first film to present itself as science fiction without any of the obvious or expected trappings of the genre. Paris in 1965 is Alphaville because Godard says it is. In part this is the director doing his usual thing of self-consciously adopting a genre; this is “science fiction” in the same way that Breathless is “crime”. But the conceptual leap was an important one for cinema, a step that freed film-makers from the need to build expensive sets and dress their cast in silver jump-suits. With Raoul Coutard’s high-contrast photography, Paul Misraki’s noirish score, Eddie Constantine’s bull-in-a-china-shop performance (he makes Ralph Meeker in Kiss Me Deadly seem soft-hearted), and the incomparable Anna Karina.

The Heat of a Thousand Suns (France, 1965)

(Previously) A one-off animated short by Pierre Kast with assistance from Chris Marker, drawings by Eduardo Luiz, and an electronic score by Bernard Parmegiani. A young man with his own spaceship solves the problem of faster-than-light travel then heads into the cosmos with his pet cat.

Fahrenheit 451 (UK, 1966)

In an oppressive future, a fireman whose duty is to destroy all books begins to question his task.

Francois Truffaut’s first colour feature has always seemed a little dull despite its incendiary subject matter and the Hitchcockian urgency of Bernard Herrmann’s score. It might have been improved with an actor other than Oskar Werner in the central role but there’s still a lot I like about this one: the music, the shots of the SAFEGE monorail, Nicolas Roeg’s striking photography, and Julie Christie in a double role. There’s also some amusement for Brits in seeing a Frenchman presenting ticky-tacky English suburbia as a soulless dystopia. With spoken titles, flat-screen TVs in every home (it’ll never happen…), and Genet novels condemned to the flames.

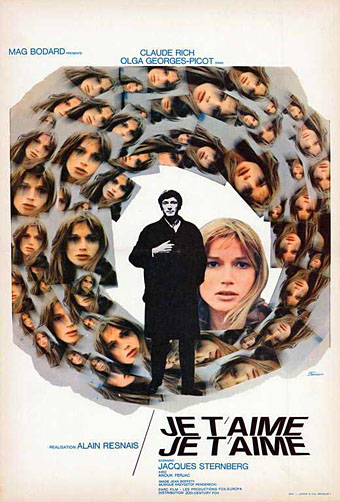

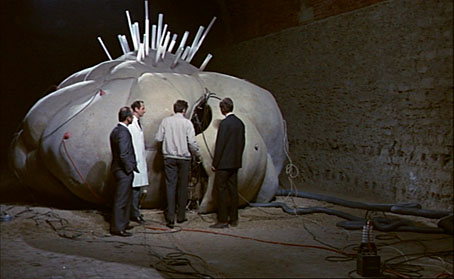

Je t’aime, Je t’aime (France, 1968)

After attempting suicide, Claude is recruited for a time travel experiment, but, when the machine goes haywire, he may be trapped hurtling through his memories.

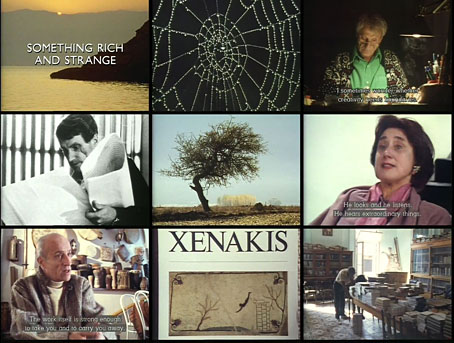

(Previously.) Much as I like toying with the idea that Last Year in Marienbad is science fiction there really isn’t anything in it that easily justifies the claim. Director Alain Resnais said that this one wasn’t SF either but it does at least feature a time machine. Resnais had collaborated with Chris Marker in the 1950s, and the pair remained friends, so it’s tempting to see this as a riff on La Jetée. (There’s even an echo of Marker’s film in the title…) Both films use a doomed romance as a focus for their examination of memory and time, and both feature choral scores, the music for this one being composed by Krzysztof Penderecki.