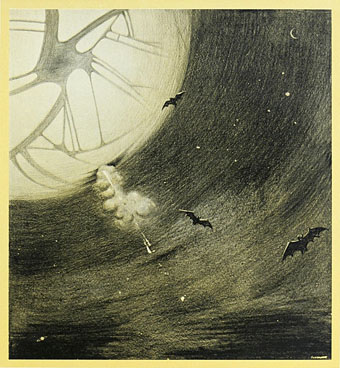

Bats in space: an illustration by Henrique Alvim Corrêa from a 1906 edition of The War of the Worlds.

• Auf wiedersehen to Florian Schneider. Until he left Kraftwerk in 2009 (or 2006 or whenever it was), Schneider had been the group’s longest-serving member, keeping things running for the few months in 1971 when Ralf Hütter was absent. The brief period when Kraftwerk was Schneider plus soon-to-be-Neu! (Michael Rother, guitar, and Klaus Dinger, drums) fascinates aficionados over-familiar with the later albums. The music they produced was a wild and aggressive take on the rock idiom but Scheider maintained the link with Kraftwerk before and after, not only instrumentally but with his ubiquitous traffic cones, as noted in this post. There’s no need for me to praise Kraftwerk any more than usual, this blog has featured at least one dedicated post about them for every year of its existence, and besides which, the group itself is still active. Elsewhere: Simon Reynolds on how Florian Schneider and Kraftwerk created pop’s future; A Kraftwerk Baker’s Dozen Special; Dave Simpson attempts to rank 30 Kraftwerk songs (good luck getting anyone to agree with this); Jude Rogers with ten things you (possibly) don’t know about Kraftwerk; Dancing to Numbers by Owen Hatherley; Pocket Calculator in five languages; Florian Schneider talks about Stop Plastic Pollution.

• Intermission is a new digital compilation from Ghost Box records featuring “preview tracks from forthcoming releases and material especially recorded for the compilation during the global lockdown”. In a choice of two editions, one of which helps fund Médecins Sans Frontières.

• How groundbreaking design weirdness transformed record label United Artists, against all odds. By Jeremy Allan.

Sex in an American suburb is not quite the same phenomenon as sex in, say, an eastern European apartment block, and sex scenes can do a great deal to illuminate the social and historical forces that make the difference. All of which is to say that sex is a kind of crucible of humanness, and so the question isn’t so much why one would write about sex, as why one would write about anything else.

And yet, of course, we are asked why we write about sex. The biggest surprise of publishing my first novel, What Belongs to You was how much people wanted to talk about the sex in a book that, by any reasonable standard, has very little sex in it. That two or three short scenes of sex between men was the occasion of so much comment said more about mainstream publishing in 2016, I think, than it did about my book. In fact, in terms of exploring the potential for sex in fiction, I felt that I hadn’t gone nearly far enough. I’ve tried to go much further in my second novel, Cleanness. In two of its chapters, I wanted to push explicitness as far as I could; I wanted to see if I could write something that could be 100% pornographic and 100% high art.

Garth Greenwell on sex in literature

• James Balmont’s guide to Shinya Tsukamoto, “Japan’s Greatest Cult Filmmaker”.

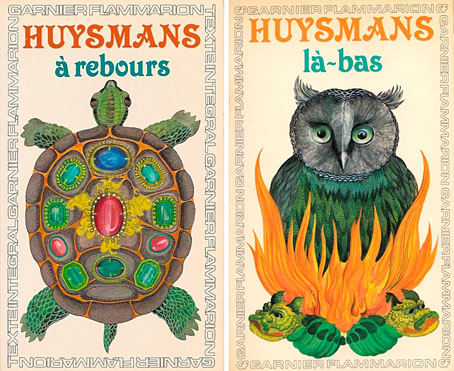

• A Dandy’s Guide to Decadent Self-Isolation by Samuel Rutter.

• Maya-Roisin Slater on where to begin with Laurie Anderson.

• The Count of 13: Ramsey Campbell’s Weird Selection.

• Adam Scovell on where to begin with Nigel Kneale.

• When John Waters met Little Richard (RIP).

• RB Russell on collecting Robert Aickman.

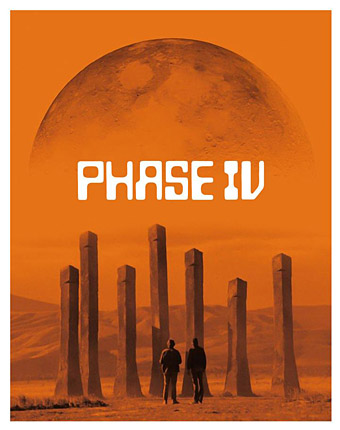

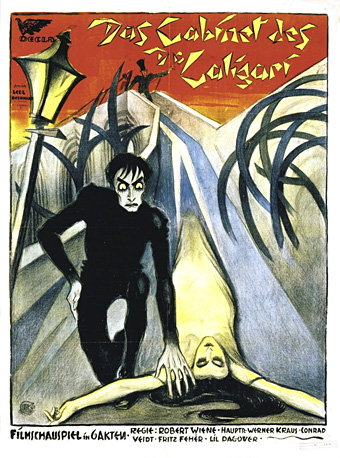

• Weird writers recommend weird films.

• Campo Grafico 1933/1939.

• Ruckzuck (1970) by Kraftwerk | V-2 Schneider (1977) by David Bowie | V-2 Schneider (1997) by Philip Glass