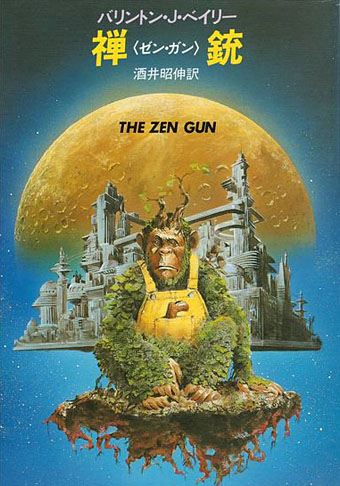

Japanese edition, 1984. Cover artist unknown.

At last, kosho Hako Ikematsu permitted himself to exult, at last he held the zen gun in his hands.

Zen in the art of electronics…

He knew its age: more than three Earth centuries. He knew its provenance: the zen master who made it had been a member of the order from which his own had originally sprung. The external appearance of the gun was a testament to certain cultural concepts: it seemed improvised, unfinished, crude, yet in its lack of polish was a feeling of supreme skill…in the Nipponese language of the time it had wabi, the quality of artless simplicity, the rustic quality of leaves strewn on a path, of a gate mended roughly with a nailed-on piece of wood and yet whose repair was a quiet triumph of adequacy and conscious balance. It had shibusa, the merit of imperfection. Only incompleteness could express the infinite, could convey the essence of reality. Hence, the unvarnished wood bore the marks of the carver’s chisel…

These qualities were themselves but superficial excrescences of the principles on which the gun acted, principles so abstruse in character that one dictum alone succeeded in hinting at them: Nothing moves. Where would it go? Pout the chimera had succeeded in using the gun as an electric beam to hurt or kill, without regard to location. But that was the most trivial of its capabilities. Only a kosho could unlock its real, dreadful purpose…

I read a novel recently that was unapologetic space opera. This isn’t something I do very often. Ryuichi Sakamoto is to blame, strange as this may seem, as a result of my spending a day or two listening to my old Sakamoto CDs. One of these, Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia, contains a short instrumental titled Zen-Gun, a piece which almost shares a title with the space opera in question, The Zen Gun by Barrington J. Bayley. I bought the Sakamoto disc in 1990, and I’ve known about the novel, which was published in 1983, for almost as long as I’ve been listening to the album. Every now and then I’ve wondered whether the two works might be connected, or at least whether Sakamoto borrowed Bayley’s title, but I’d never considered reading the novel until now.

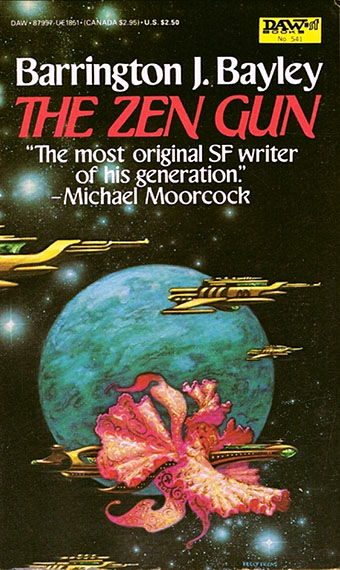

US edition, 1983. Cover art by Kelly Freas.

Barrington Bayley (1937–2008) is a writer whose works I’d mostly avoided while he was alive. This despite the continual praise he received from Michael Moorcock, and the acknowledgement by William Burroughs in Nova Express for an idea borrowed from a Bayley story with a Burroughs-like title, The Star Virus. (Samples of Burroughs’ voice happen to turn up on an album that Ryuichi Sakamoto recorded after Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia, the Bill Laswell-produced Neo Geo. Make of this what you will.) Bayley was the odd man out among the British writers of science fiction’s New Wave for persevering with hard SF, a sub-genre I don’t enjoy reading very much unless it’s by a trustworthy writer. All genres have their share of bad writers but science fiction, especially the variety concerned with space-faring and futuristic technology, has historically been home to more than most. I already knew that Bayley could write a decent story—he appeared regularly in the pages of New Worlds magazine—but I feel I’ve been doing him a disservice by ignoring his novels for so long.

The thing that really pushed me towards The Zen Gun was reading the Wikipedia entry for the novel which includes the following praise from Bruce Sterling:

Yet Bayley’s elemental energy, his mastery of the sense of wonder, cannot be denied. His work is the very antithesis of tired hackdom. To invent an entire self-consistent cosmology and physics for a $2.50 DAW paperback…is one of those noble acts of selfless altruism that keep SF alive.

Then there’s this comment about the mysterious Zen Gun itself, a piece of wood carved into the shape of a pistol which is capable of destroying entire suns: “Powerful as the weapon is, its existence is a paradox, as only those who have attained inner peace can use it.” After reading this I knew I had to read the novel.