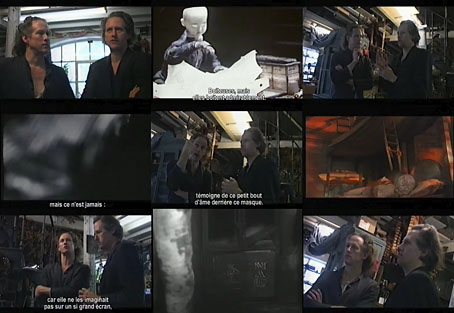

Interviews with the Brothers Quay have been quite plentiful in recent years—some may be found on their DVD releases—but for the Quay enthusiast some are more notable than others. This half hour programme for French TV stood out for me for taking place inside the London studio where many of the Quays’ short films have been made. The interview was conducted in 2002, and one of the brothers mentions that they may be leaving the premises soon; one of their exhibition catalogues has a recent photo of the studio so we can assume this wasn’t the case.

Since this was made for an animation series the discussion is mainly about the brothers’ animation techniques. There’s also some barbed comment later on about the conservative state of British television. The UK’s Channel 4 was a great champion of animation in its early days, and the channel’s budget for short films helped finance many of the early films by the Quays and their producer Keith Griffiths. This was at a time when there were only four TV channels to choose from; today we have numerous channels but no room on any of them for unusual or experimental fare. Similar sentiments are voiced on the BFI’s recent collection of Alan Clarke films. Just as there’s no room for the Quays in the current climate, there’s no room either for the single dramas that directors like Clarke were making in the 1970s and 1980s.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Quay Brothers archive