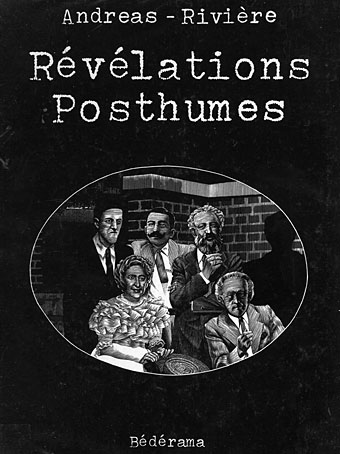

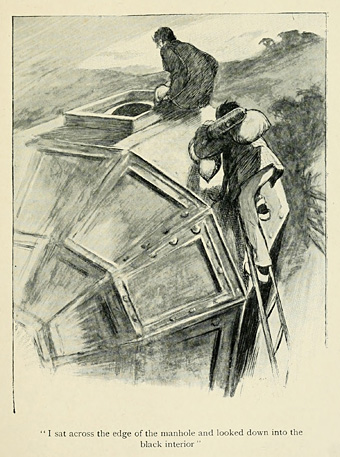

Le livre est arrivé. Révélations Posthumes, written by François Rivière and illustrated by Andreas (Martens), turned out to be better than I expected: 58 pages of very sharp black-and-white illustration on coated paper, and in the hardcover album format which has long been my favourite mode of presentation for comic books. The quality of the printing has made me realise that the reprint of RHB in The Cosmical Horror of HP Lovecraft (see this post) had blacked in many of the fine lines of Andreas’s scraperboard drawings, resulting in darker panels with diminished detail. Here you see the story as it was drawn, and—more importantly—with all of its pages present. The reprint of La Femme de Cire du Musée Spitzner (The Spitzner Museum’s Wax Woman) fared much better in Escape magazine.

Auteur et artiste.

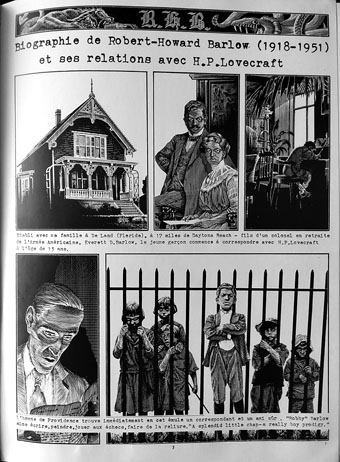

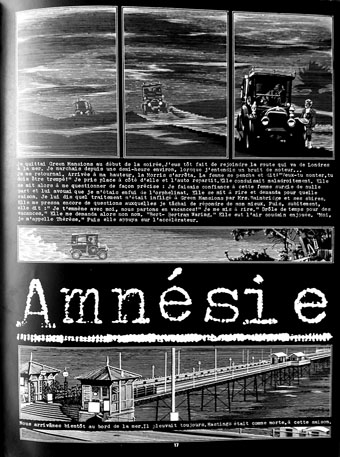

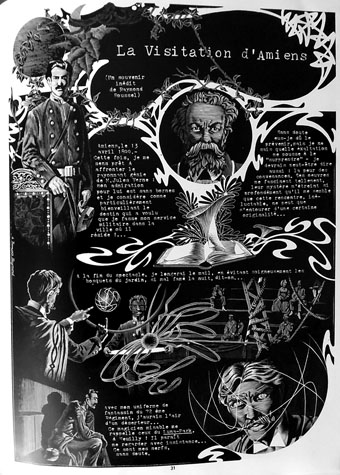

The other three stories in this collection are all new to me. Amnésie concerns the strange disappearance of Agatha Christie in December 1926, an event which has been the source of much unresolved speculation (Monsieur Rivière is apparently a great Christie enthusiast); La Visitation d’Amiens recounts a meeting in 1899 between the young Raymond Roussel when he was posted to Amiens during his military service, and the aging Jules Verne, whose fantastic inventions would influence Roussel’s 1914 novel, Locus Solus; Le Crime de la Mosquée is set in Rochefort-sur-Mer in 1936, and concerns a young Englishman, Alfred J. Nobbs, visiting the home of the late Pierre Loti, another writer whose works inspired Raymond Roussel. Writers dominate this book, which no doubt explains the choice of typewritten captions.

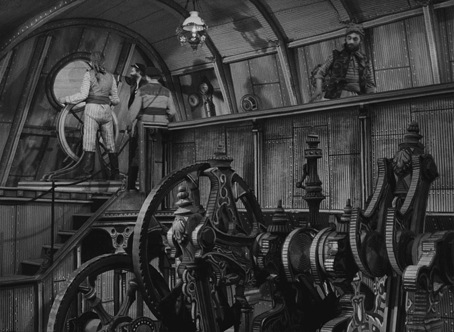

The introduction by Pierre-Jean Rémy suggests that all the stories are combinations of fact and fiction, but the Lovecraft and Robert H. Barlow story seems to be based in full on Barlow’s biography, while the Spitzner Museum story concerns a Belgian painter, Pol Delmotte, who doesn’t appear to exist at all outside these pages. (“Delmotte” is very probably based on Paul Delvaux but the events of the story would have prevented him being named as such. Thanks to Paul R. for the comments noting this.) Whatever the case—and it’s impossible for me to really tell when my French is so poor—the artwork is superb. The very similar look of the Barlow and Spitzner stories, all elongated panels and the occasional half-toned photograph, had led me to expect a similar form for the other stories but Andreas varies his layouts from story to story. Amnésie adds a black background to the pages, while La Visitation d’Amiens removes most of the panel borders to create a series of floating vignettes, Art Nouveau flourishes and other decoration. Le Crime de la Mosquée differs from the rest by filling each page with a landscape-ratio composition, a rare thing in comics. The backgrounds of the last few pages present a series of architectural interiors whose meticulous rendering rivals the engravers of the 19th century for veracity and detail. The book as a whole shows Andreas to be a master of the scraperboard technique but this volume also seems to comprise the totality of his work in the medium. His later books contain a great quantity of exceptional art but the pen-and-ink style he uses is often sketchier and more stylised, inevitably so given the pressures of comic-book production. I’m tempted to hope that Titan might one day produce a English translation of this book but they’d be more likely to do the Rork saga or the rest of the Cromwell Stone series first, and there are many volumes of those. Révélations Posthumes has at least been reprinted several times since 1980 so it’s easy to find.

Continue reading “Révélations Posthumes by Rivière and Andreas”