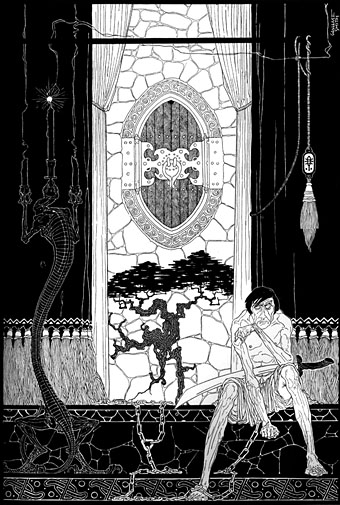

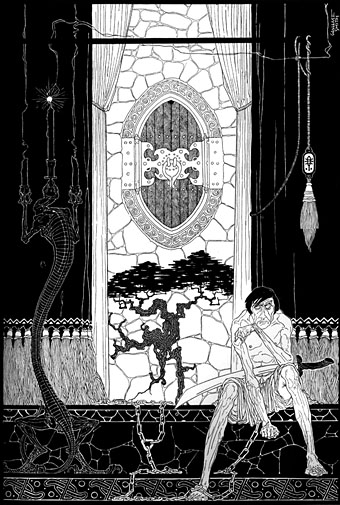

Fantazius Mallare by Wallace Smith (1922).

Ben Hecht (1894–1964) is remembered today as a notable Hollywood screenwriter. He won the first screenplay Oscar for Underworld in 1927, wrote the great screwball comedies Nothing Sacred and His Girl Friday (based on his play with Charles MacArthur, The Front Page), and worked with directors such as Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock, among others. His work as a novelist is inevitably overshadowed by these achievements, not least the two curious books he wrote when he was in his twenties, one of which ended up being prosecuted for obscenity.

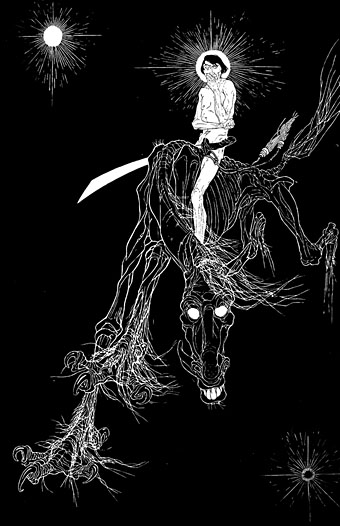

A novel of decadence and mystic existentialism, Fantazius Mallare is a story of a mad recluse—a genius sculptor and painter who is at war with reason. Rather than commit suicide, his doting madness dictates that he must revolt against all evidence of life that exists outside himself. He destroys all of his work and then seeks out a woman who will devote herself to his Omnipotence. What follows is a glorious trek into a horrifying enlightening insanity.

Fantazius Mallare: A Mysterious Oath was first published in 1922 in a limited run intended for private distribution, most of which ended up being seized and destroyed by the authorities. The book is generally described as being a decadent work after the manner of Joris-Karl Huysmans‘ À rebours although this is a lazy comparison. Huysmans’ Des Esseintes is far more effete than the morose Fantazius Mallare, his exploits more cerebral. Huysmans’ prose is also more considered:

It was obvious that the decadence of this family had followed an unvarying course. The effemination of the males had continued with quickened tempo. As if to conclude the work of long years, the Des Esseintes had intermarried for two centuries, using up, in such consanguineous unions, such strength as remained.

There was only one living scion of this family which had once been so numerous that it had occupied all the territories of the Ile-de-France and La Brie. The Duc Jean was a slender, nervous young man of thirty, with hollow cheeks, cold, steel-blue eyes, a straight, thin nose and delicate hands.

Hecht meanwhile begins like this:

Fantazius Mallare considered himself mad because he was unable to behold in the meaningless gesturings of time, space and evolution a dramatic little pantomime adroitly centered about the routine of his existence. He was a silent looking man with black hair and an aquiline nose. His eyes were lifeless because they paid no homage to the world outside him.

When he was thirty-five years old he lived alone high above a busy part of the town. He was a recluse. His black hair that fell in a slant across his forehead and the rigidity of his eyes gave him the appearance of a somnambulist. He found life unnecessary and submitted to it without curiosity.

What follows is a work of vigorous grotesquerie and misanthropy that might almost seem parodic if the sincerity of the author’s cynicism wasn’t so evident. Before heading for Hollywood, Hecht worked as a journalist in Chicago and his eye for hypocrisy gave him much to be cynical about. Des Esseintes collects works of art to assuage his weariness with the world; Fantazius Mallare has no time for such preciousness:

Rising from his chair Mallare attacked, one by one, the canvases and statues. Goliath watched him in silence as he moved from pedestal to pedestal from which, like a company of inert monsters, arose figures in clay and bronze. The first of them was a man four feet in height but massive-seeming beyond its dimensions. Mallare had entitled it “The Lover.”

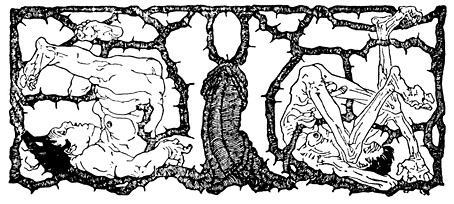

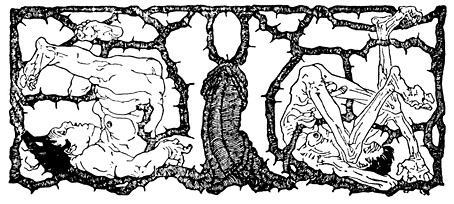

Its legs were planted obliquely on the pedestal top, their ligaments wrenched into bizarre muscular patterns. Its body rose in an anatomical spiral. From its flattened pelvis that seemed like some evil bat stretched in flight, protruded a huge phallus. The head of the phallus was enlivened with the face of a saint. The eyes of this face were raised in pensive adoration. At the lower end of the phallus, the testicles were fashioned in the form of a short-necked pendulum arrested at the height of its swing. The hands of the figure clutched talon-like at the face and the head was thrown back, as if broken at the neck. Its features were obliterated by the hands except for the mouth which was flung open in a skull-like laugh.

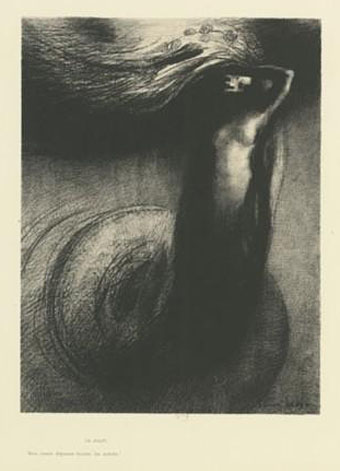

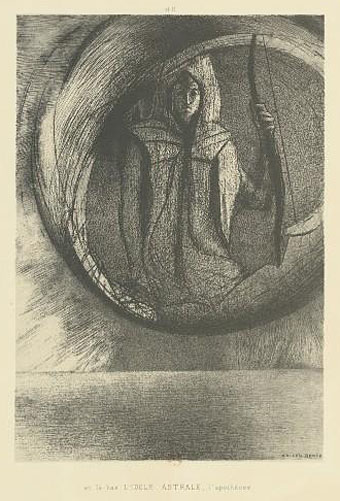

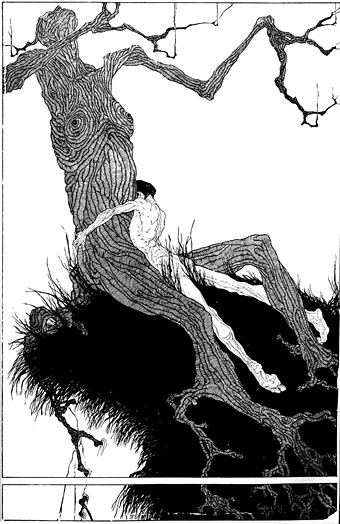

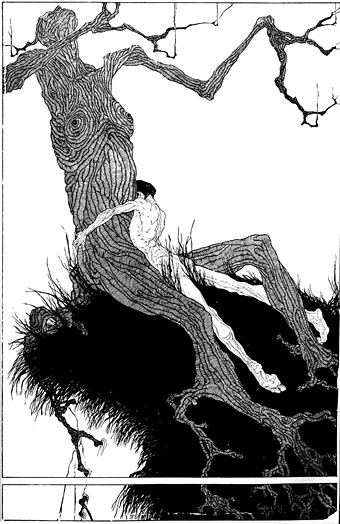

Hecht’s book was illustrated by Wallace Smith (1888–1937) whose careful delineations seem to owe something to Harry Clarke. Smith didn’t spare the salacious details and artist and writer ended up being fined $1000 each when the books were seized. Book fanzine It Goes on the Shelf throws some interesting light on this incident in a review of a Hecht biography:

…my interest in Hecht is mostly that he wrote a book, Fantazius Mallare, illustrated by Wallace Smith. Smith was said by Ronald Clyne to have gone to jail for the Mallare artwork, but apparently this was an exaggeration—he and Hecht were, however, fined $1000 each for “obscenity”; and $1000 was quite a lot of money in 1924. The particular points I was curious about were where the rest of the Wallace Smith artwork is—he could hardly have developed that style in the handful of drawings that have been published; and what happened to the copies of Fantazius Mallare seized by the US government—the book did not seem to be as scarce as would have been expected if they had seized even half of the 2000-copy edition. MacAdams was able to answer this last question to some extent—after the obscenity conviction, the publisher made another 2000 copies and sold them ‘under the counter’. However, MacAdams and I discovered that we both have copies of the original numbered edition, and that mine is #587 while his is #1900 and something—so what did the goverment seize?

It should be noted that Hecht and Smith went to a great deal of trouble to have themselves convicted of obscenity. They had wanted to create a test case of the federal obscenity law and have a show trial in order to turn public opinion against it by ridicule. Hecht also intended to enter a million-dollar civil suit for defamation of character against John Sumner and his infamous Society for the Suppression of Vice if Sumner attacked his book. The famous Clarence Darrow was to have been their attorney. The plan was to send review copies of Fantazius Mallare to all of the literary lights of the time, and then have Darrow call these people as expert witnesses at the trial. Alas, the scheme foundered on the unforeseen pusillanimity of the literary establishment—only HL Mencken agreed to appear as a witness. In the end there was no trial because Hecht and Smith endered a plea of nolo contendere.

Their treatment failed to impress DH Lawrence. In a review for Berkeley’s The Laughing Horse he wrote:

These drawings are so completely without irony, so crass, so strained, so would-be. There’s nothing in it but the author’s attempt to be startling…. The word penis or testicle or vagina doesn’t shock me. Why should it? Surely I am enough a man to be able to be able to think of my own organs with calm, even with indifference. It isn’t the names of things that bother me; nor even ideas about them. I don’t keep my passions, or reactions, or even sensations IN MY HEAD. They stay down where they belong….

…all these fingerings and naughty words and shocking little drawings only reveal the state of mind of a man who has NEVER had any sincere, vital experience in sex…. If Fantazius wasn’t a frightened masturbator he knows that sex contact with another individual meant a whole meeting, a contact between two natures, a grim recontre, half battle and half delight, always, and a sense of renewal and deeper being afterwards….The great gods pulse in the dark, and enter you as darkness through the lower gates. Not through the head.

Fantazius Mallare seems to me such a poor, impoverished, self-conscious specimen.

According to The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural Smith largely abandoned drawing after this episode, following Hecht to Hollywood where he became a minor screenwriter and novelist. Hecht was undeterred and wrote a sequel which appeared in 1924, The Kingdom of Evil: A Continuation of the Journal of Fantazius Mallare, like its predecesor also produced in a limited run.

The Kingdom of Evil continues the journal of the mad recluse Mallare, who has decided to live beyond reality, now an empty, repugnant memory. It is Mallare’s desire to find a world in which he belongs, and out of his madness he creates the monstrous Kingdom of hallucination: “Luminous and strange, its roofs careening like wing-stretched bats it lay encircled by hills—a Satanic toy, a thing of unearthly marvels. Its painted streets beckoned to Mallare. Its demons, horrors and lusts waited for him…”

The lusts aren’t so lavishly depicted this time, Hecht no doubt wanted to avoid another $1000 fine. This is a shame since the second book is longer but less interesting despite flights of fancy such as the following, which reads like a description of some of the horrors seen in Harry Clarke’s Faust illustrations:

Julian turned away quickly. But he remained without moving. Around us in every direction were dreadful, nauseating figures; two-headed things with faces drooping at the ends of wilted stalks; creatures with boneless limbs and bodies like pouches; creatures with swollen and pendulous heads riveting them to the earth; animate snail-like masses of flesh, hair-matted and mucous-covered; thick, serpentlike bodies that struggled to stand erect; half-formed heads that raised themselves above appalling disfigurements. I could not believe them alive at first and thought they must be matter that had erupted fungus fashion out of the earth. But staring I detected amid these obscene and tumorous shapes, horrifying human fragments—the arm of a man, the perfect breasts of a woman; human eyes staring out of putrescent and formless growths, human lips red and grimacing in swollen smiles. Around us they crept, emitting sounds, clawing at the air with fingers and stumps—a convulsive debris of faces, limbs and fetal distortions moving like foul bags of life.

Julian fled. I stood unable to move until one of them, tall as a man, its bulbous head rising out of a discolored sack of flesh, turned its face toward me. For the moment I looked at it a horror contracted my skin. I saw stamped upon this hideous growth and half-hidden by a cowl of skin a face I knew-a face with melancholy eyes and wide brooding mouth; a man’s face, perfect and thinking, its hair falling in a black slant across its brow.

“My face!” I screamed.

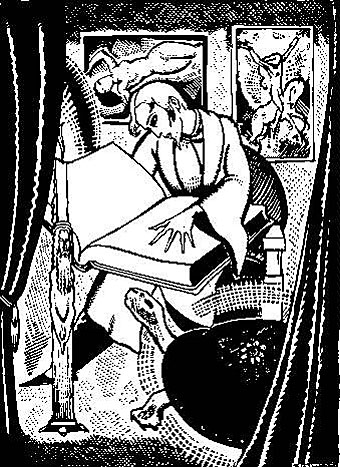

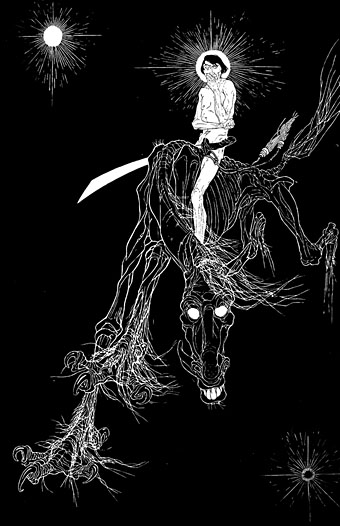

The artist engaged to try and match the prose was Anthony Angarola, a poor substitute for Smith despite the lasting praise of HP Lovecraft (see this earlier post). Angarola’s work resembles an imitator of S Clay Wilson pastiching Harry Clarke, if such a thing is possible, and it’s likely that it was this book that gave Lovecraft a good look at Angarola’s work. HPL would have baulked at the sexual content of Fantazius Mallare had he seen it.

The world hadn’t heard the last of the misanthrope, however, as he returned in a bizarre film adaptation, The Scoundrel, in 1935, giving Noël Coward his first starring role:

This odd morality play is set in the hellish environment of a decadent and pseudo-intellectual NYC publishing house, and is written and directed by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur. It was inspired by Hecht’s earlier novel, Fantazius Mallare. This unique fantasy film sets an acerbic atmosphere of backbiting and meaningless existence for literary types. The film’s climax leaves the realistic publishing world and enters a metaphorical world of spiritual values. Unfortunately this stagy but cleverly sophisticated story turns into a pretentious mess. However, the film was able to collect an Oscar for Best Original Story.

Both books are out of print at present but you can read Fantazius Mallare online here. Kingdom of Evil is harder to find but the pair have been reprinted often enough so there are plenty of secondhand copies around.

Update: A scan of the first edition of Fantazius Mallare is now available at the Internet Archive.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive