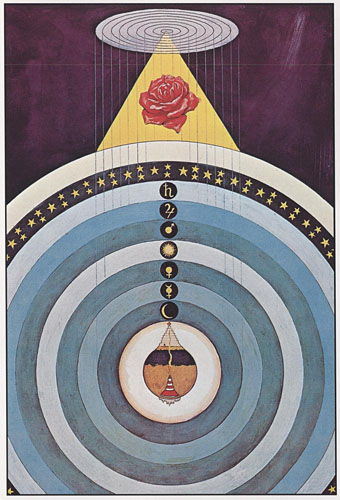

I wouldn’t usually post so many illustrations but these depictions by J. Augustus Knapp for Etidorhpa by John Uri Lloyd add a great deal to the attractions of this early work of science fiction. Lloyd’s book is subtitled The End of Earth; The Strange History of a Mysterious Being; The account of a remarkable journey as communicated in manuscript to Llewellyn Drury who promised to print the same, but finally evaded the responsibility. The novel was published in 1895, and shares features with similar works that concern travellers exploring the interior of the Earth. What sets it apart is a degree of imagination that generated enough interest for it to be reprinted many times.

Science fiction and fantasy evolved so rapidly in the early 20th century that the products of previous centuries often seem uninventive in comparison. Whatever hidden cities, lost continents or subterranean kingdoms are promised, too many of them reveal a race of pompous individuals, usually clad in Greek, Roman or Egyptian attire with little variety to their civilisations unless their world is also populated by the odd monster or two. The manuscript in Lloyd’s novel relates a journey to the Earth’s interior by a bearded, white-haired character variously named I-Am-The-Man and The-Man-Who-Did-It who reads his adventures in a series of visits to the irresponsible Llewellyn Drury. I-Am-The-Man is kidnapped by a secret society who take him to a cave in Kentucky where he’s eventually delivered into the care of a mysterious, unnamed guide from the subterranean world:

The speaker stood in a stooping position, with his face towards the earth as if to shelter it from the sunshine. He was less than five feet in height. His arms and legs were bare, and his skin, the color of light blue putty, glistened in the sunlight like the slimy hide of a water dog. He raised his head, and I shuddered in affright as I beheld that his face was not that of a human. His forehead extended in an unbroken plane from crown to cheek bone, and the chubby tip of an abortive nose without nostrils formed a short projection near the center of the level ridge which represented a countenance. There was no semblance of an eye, for there were no sockets. Yet his voice was singularly perfect. His face, if face it could be called, was wet, and water dripped from all parts of his slippery person.

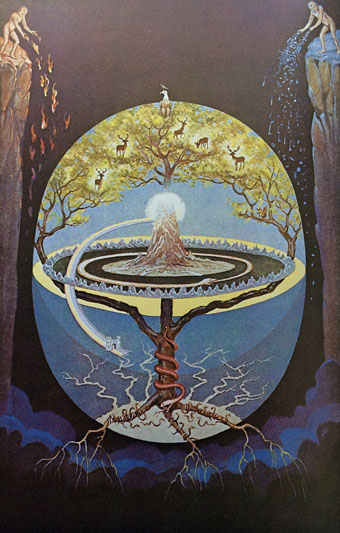

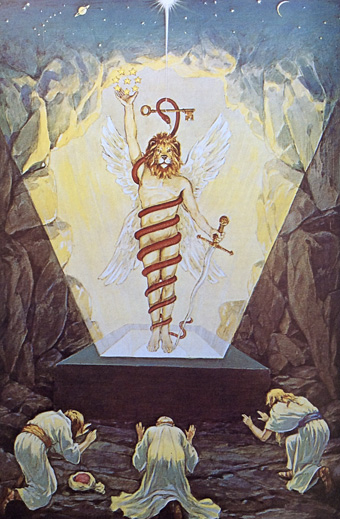

The illustrations by J. Augustus Knapp show the guide as naked but conveniently sexless. The pair descend into the Earth’s interior where they encounter a succession of wonders, from giant fungi (possibly derived from A Journey to the Centre of the Earth) and a sea of “crystal liquid” which the pair traverse in a metal boat, to a variety of strange fauna and flora. Knapp’s illustrations make the journey seem much more interesting than it is on the page where Lloyd spends far too much time lecturing the reader—there’s a chapter about the evils of drunkenness—or having I-Am-The-Man relate his continual bewilderment. “Etidorhpa”, it turns out, is “Aphrodite” reversed, and Etidorhpa herself appears as the embodiment of love at the culmination of what has become a spiritual journey rather like a weak precursor of David Lindsay’s extraordinary A Voyage to Arcturus (1920). Lindsay had the good sense to write a continuous narrative whereas Lloyd frequently interrupts his story with scientific speculations that seek to qualify some of the less outlandish features of his interior world. There’s also a curious note from the author on page 276 about the various properties of intoxicating drugs, and the possibility that they might be combined by a chemist to create strange visions for a writer. Lloyd was a chemist as well as a writer so the speculation that he might have experimented on himself—and thus produced this book—is understandable. Speculation aside, L. Sprague de Camp dismissed the novel as “unreadable” (despite its multiple reprintings) whereas HP Lovecraft apparently enjoyed it. You can judge for yourself here.

Continue reading “Etidorhpa by John Uri Lloyd”