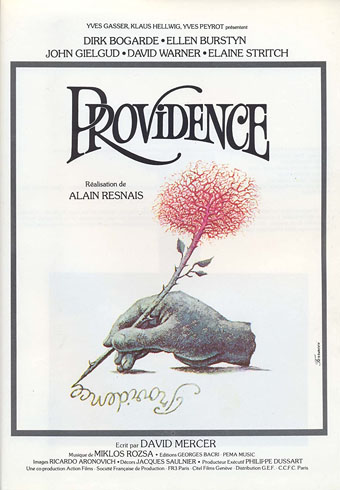

Art by René Ferracci.

Continuing an occasional series about artworks in feature films. Most people know HR Giger’s work via his production designs for the Alien films; a much smaller number of people also know about his designs for Jodorowsky’s unmade film of Dune, but hardly anyone knows that his art first appeared in a major film two years before Alien was released. This isn’t too surprising when the film in question, Providence, directed by Alain Resnais, has been increasingly difficult to see since 1977; the film isn’t mentioned in any of Giger’s books either, a curious omission for an artist who spent his career logging every public appearance of his work.

Providence began life as a collaboration between Resnais and British playwright David Mercer, with the resulting script leading to a Swiss/French co-production that was filmed in English. The film has an exceptional cast—Dirk Bogarde, Ellen Burstyn, John Gielgud, Elaine Stritch, David Warner—marvellous photography by Ricardo Aronovitch, and a sumptuous score by Miklós Rózsa. If you’re the kind of person who regards awards as designators of quality then it’s worth noting that Providence won 7 Cesar Awards in 1978, including the one for best picture. Yet despite all this, and despite being regularly described as a peak of its director’s career there’s only been a single DVD release which is now deleted. I’d been intending to write about the film for some time but first I had to acquire a decent copy to watch again; this wasn’t an easy task but I managed to “source” a version that was better than the VHS tape I used to own.

For most of its running time Providence is a film about artistic invention, more specifically about the process of writing. Clive Langham (John Gielgud) is an ailing author spending a sleepless night alone in his huge house, “Providence”, wracked by unspecified bowel problems, painful memories and fears of impending death. To distract himself from his troubles he drinks large quantities of wine while mentally sketching a scenario for a novel in which the people closest to him are the main characters. In this story-within-the-story Langham’s son, Claude (Dirk Bogarde), is a priggish barrister whose primary conflicts are with his absent father, his bored wife, Sonia (Ellen Burstyn), and a listless stranger, Kevin (David Warner), who Sonia has befriended and seems attracted to even though Kevin won’t reciprocate. While Claude cajoles and insults the pair he also conducts an affair of his own with Helen (Elaine Stritch), an older woman who resembles his dead mother. The scenario is elevated from being another mundane saga about middle-class infidelities by its persistently dream-like setting, and by the interventions and confusions of its cantankerous author. If you only know John Gielgud from his later cameos playing upper-class gentlemen then he’s a revelation here, boozing and cursing like the proprietor of Black Books. Between spasms of illness and self-pity Langham shuffles his playthings around like chess pieces, revising scenes while trying to keep minor characters from interfering; “Providence” isn’t only the house where Langham lives but also the watchful eye of its God-like author. Meanwhile, his characters bicker and chastise each other, paying little attention to the disturbing events taking place in the streets outside: terrorist bombings, outbreaks of lycanthropy, and elderly citizens being rounded up for extermination.