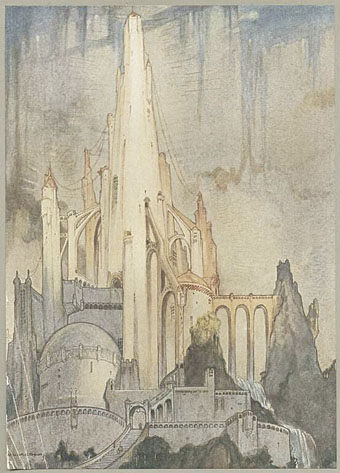

The Temple, an illustration from The Ship that Sailed to Mars (1923) by William Timlin.

• “With the grotteschi, Piranesi produced hybrid forms of ornament juxtaposed in an array without regard to single-point perspective. With his capricci, he brought disparate structures into a landscape that existed only within the borders of the plate. Perhaps because of his early fidelity to accuracy and the long tradition of printmaking as a medium for the measured representation of antique forms, Piranesi’s capricci take on a particularly fantastic aura.” Susan Stewart on the ruinous fantasias of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, one of whose etchings happens to be providing the page header this month.

• At Dangerous Minds: 23rd Century Giants, the incredible true story of Renaldo & The Loaf! Oliver Hall conducts a long and very informative interview with two of Britain’s strangest music makers.

• New music: Nightcrawler by Kevin Richard Martin, recommended to anyone who enjoys the nocturnal doom of Bohren & Der Club Of Gore; and Murmurations by Lea Bertucci & Ben Vida.

“Throughout the book, McCarthy writes as if he knows something that more conventional historians aren’t always keen to accept: that the past doesn’t always make sense, that it’s often cruel and irrational, and that some things aren’t so explainable. History is not a book waiting to be opened so much as a Pandora’s box that might curse us and leave us chastened by what we find inside.”

Bennett Parten on Cormac McCarthy’s baleful masterpiece, Blood Meridian

• “Inside me are two wolves and they are both paintings by Kazimierz Stabrowski.” S. Elizabeth‘s latest art discoveries.

• At Wormwoodiana: Mark Valentine on Arthur Machen and the mysteries of the Grail.

• RIP Betty Davis and Douglas Trumbull.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Tobe Hooper Day.

• Temple Bells (1959) by Frank Hunter And His Orchestra | Temple Of Gold (1960) by Les Baxter | Temple (2018) by Jóhann Jóhannsson