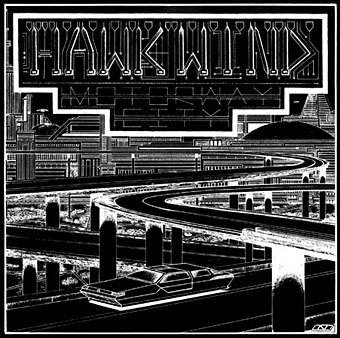

Motorway City by Hawkwind, Flicknife Records single (1983).

This month’s issue of Record Collector magazine has a feature about Hawkwind which featured my Motorway City sleeve among its illustrations. It was odd seeing this again, being a single it doesn’t turn up so often and it has the distinction of being one of the oldest of my works in print. Although the single was released in 1983, the drawing was done in 1980 (I was 18 at the time) and it ended up with Dave Brock somehow.

The A-side is taken from the Zones album, which sports one of my more successful cover illustrations for the band, and the song is a Ballardian eulogy to driving on motorways at night. Despite their reputation for being a bunch of spaced-out hippies, Hawkwind were frequently drawn to the harder side of things (Lemmy used to shout “Die! Die!” at their tripping audience and was proud of freaking people out), and this song isn’t even science fiction, despite my flat futuristic cityscape in the background. Before he finished with the band for good, singer Robert Calvert wrote two songs based on JG Ballard books, High Rise and the punk- and Crash-derived thrash piece Death Trap, both on the PXR5 album from 1979. Motorway City was written around the same time and it’s a shame it didn’t have Death Trap on the B-side instead of yet another version of Master of the Universe. My drawing was done as black on white but the record company smartly (for once) reversed out the design which I always felt made it look a lot better, as well as fitting more with the night-driving theme.

Also this month, I’m in the process of reworking the website a bit which means making more prints of artwork available. I’ve started with some of the Lovecraft pictures, which is always the most popular stuff but I’ll gradually be working through everything and setting up PayPal facilities for other items. Many pictures and designs can already be had as prints at CafePress but that system is best for t-shirts and other goods, it lacks the personal touch which people often want from a signed print.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Hawkwind: They’re still feeling mean

• Barney Bubbles: artist and designer