The ideas ruins evoke in me are grand. Everything comes to nothing, everything perishes, everything passes, only the world remains, only time endures. How old is this world! I walk between two eternities.

Denis Diderot, 1767

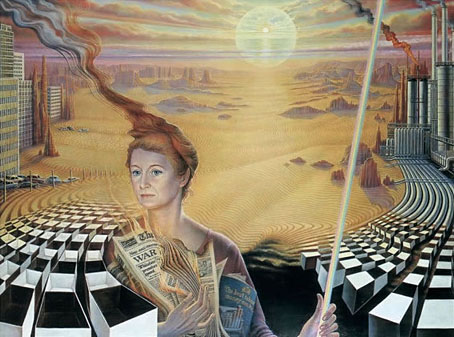

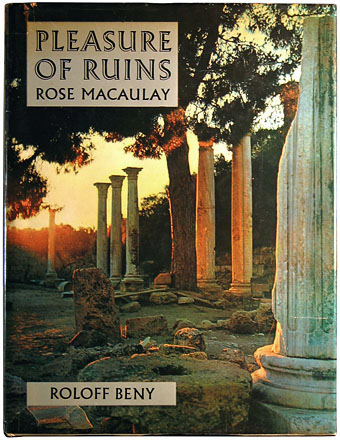

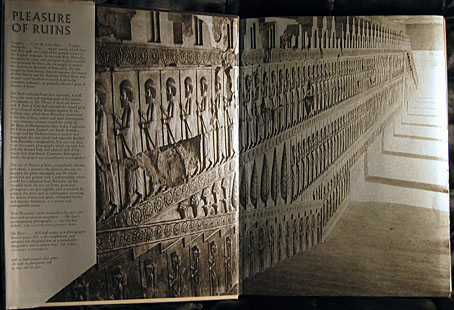

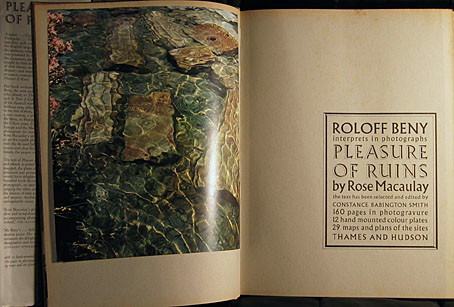

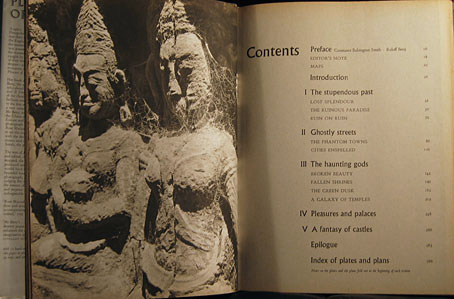

Ruins, as Diderot observed, are the memento mori of civilisations, a reminder that the apparent permanence of architecture is illusory: this too shall pass. Rose Macaulay explored the melancholy pleasure inspired by this contemplation in Pleasure of Ruins (1953), a book I was reminded of on two separate occasions this weekend. Before I get to those I can’t resist showing something of my own copy of Macaulay’s study, a heavyweight volume (286 pp, 346mm x 260mm) published by Thames & Hudson in 1964. This was the third book by Canadian photographer Roloff Beny who made a habit of photographing ancient ruins. Here he visits Angkor, Tintern Abbey, Persepolis, Petra, Baalbek, Leptis Magna, Chichen Itza, Machu Picchu and elsewhere to embellish Macaulay’s text with 160 photogravure pages, 12 tipped-in colour plates, and maps of the locations on fold-out spreads. Beny also designed the book which even in my rather scuffed and damp-afflicted copy is an impressive example of the mass-produced edition as work-of-art.

Metallic silver printing on the endpapers.

Rick Poynor provided the first mention of Macaulay’s book in a piece of polemic justifiably disputing the pejorative term “ruin porn”, an epithet that’s appeared recently among critics of those fascinated by photos of abandoned Detroit, or Battleship Island off the coast of Japan. If photos of ruins are “ruin porn” then Roloff Beny’s books must count as hardcore, while my National Trust Book of Ruins is evidently a government-sponsored sex manual. Poynor notes the criticism being a particularly American one, and wonders whether some Americans fail to appreciate the long cultural and political history of the ruin in Europe. Plenty of European cities have ruins in their midst, whether ancient ones like London Wall and the centre of Rome, or more recent ones like the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin and Coventry Cathedral, both partially destroyed during the Second World War. An appreciation of ruins began in the 18th century and evolved in tandem with the emergence of antiquarianism. Prior to this, ancient ruins were either a nuisance or a resource to be plundered for their stones. (Or, as can be seen in some of Piranesi’s Views of Rome, a convenient support for shops and houses.)

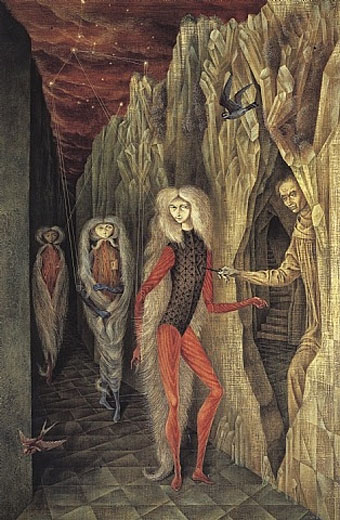

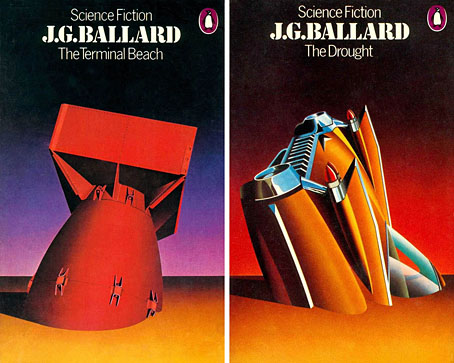

From ruin porn to Ruin lust: our love affair with decaying buildings, an essay by Brian Dillon which covers similar ground to Poynor’s piece, and discusses Rose Macaulay’s interest in ruins, an interest that survived being bombed out of her home during the war. This is a great run through the usual suspects, from the Romantics (with a nod to Fonthill Abbey) to JG Ballard’s obsession with the remnants of the Cold War and the Space Age. Dillon mentions the painting John Soane commissioned from Joseph Gandy showing his Bank of England building as a future ruin. And he also recounts the story (which I heard repeated recently in a Robert Hughes documentary) of Hitler’s demands to Albert Speer during their planning of the future capital of the Third Reich, Germania, that the buildings should make good ruins. It’s impossible to imagine anyone today planning a building as a future ruin even though many will end up that way, if they last at all.

If it wasn’t already apparent that ruins are the thing du jour, a current exhibition at Dundee Contemporary Arts is of photographic prints by Jane and Louise Wilson showing views of abandoned Pripyat, better known as the town at the heart of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Rick Poynor refers to Pripyat in his piece, and it’s also an inevitable subject of discussion in Geoff Dyer’s latest book, Zona, an exploration of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker where a disused power station adds a more sinister quality to the pleasure of ruins.

More pages from Roloff Beny’s book follow.