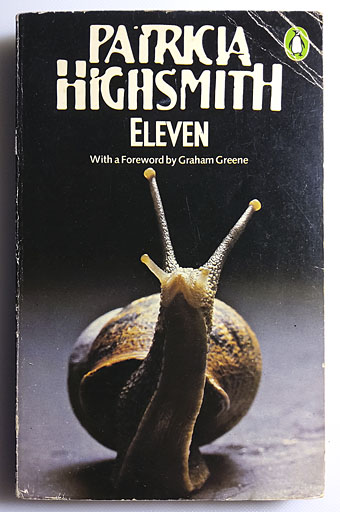

Penguin, 1980; photo by David Thorpe.

A post for Patricia Highsmith, born 100 years ago today. Filling the cover of one of Highsmith’s books with a photograph of a snail may seem like a bizarre or even perverse decision but Eleven is a collection of short stories, two of which concern the author’s beloved gastropods. The snails in The Snail-Watcher and The Quest for ‘Blank Claveringi’ aren’t so lovable, however, and both stories make frequent appearances in horror collections. The Quest for ‘Blank Claveringi’ was even the lead story in The 6th Fontana Book of Great Horror Stories, prompting another snail cover.

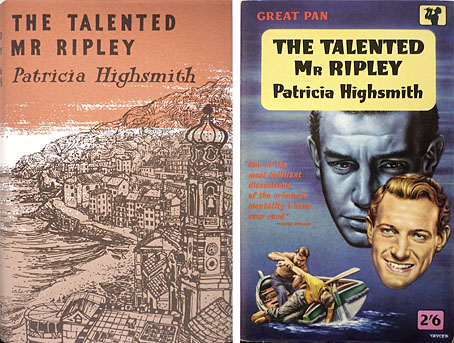

left: First UK edition, Cresset Press, 1957; no artist credited. Right: Pan, 1960; cover art by David Tayler.

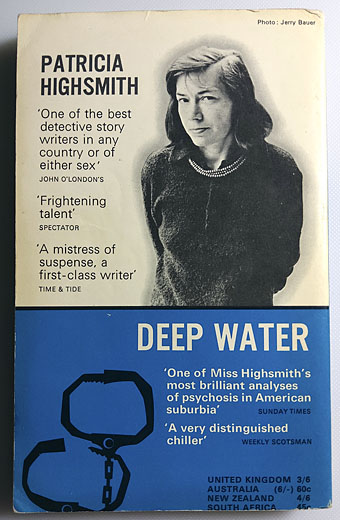

Highsmith’s enduring popularity means that most of her books have remained in print since their initial publication so there are many covers to look at. They’re a very mixed bag, as is often the case with thrillers where two design approaches predominate: symbolism that can either be vague or suggestive, or some kind of illustration which always runs the risk of spoiling the story. Nick Jones’ Existential Ennui blog contains a number of posts about Highsmith’s books, including this one which shows off his collection of first editions. I was surprised to see the bland cover for the original UK publication of The Talented Mr Ripley, an illustration that would suit any number of stories set on the Mediterranean coastline, and which gives no indication of the tangled web of deceit and murder inside the book. Perhaps this is a good thing but it feels like a missed opportunity. Another of Jones’ posts concerns Highsmith paperbacks, and here we see the spoilerish approach with the same novel featuring a painting that shows Ripley pushing Dickie Greenleaf’s body into the sea. This was common form for thriller paperbacks at the time: “Yes, there’s murder in this one!” My 1966 Pan paperback of Deep Water features a similar scene of body disposal (which rather spoiled the story while I was reading it) but it also has the following photo of the author on the back, looking as though she’s wondering how to dispose of your body when the time comes.

Pan, 1966; photo by Jerry Bauer. Also another book that features snails.

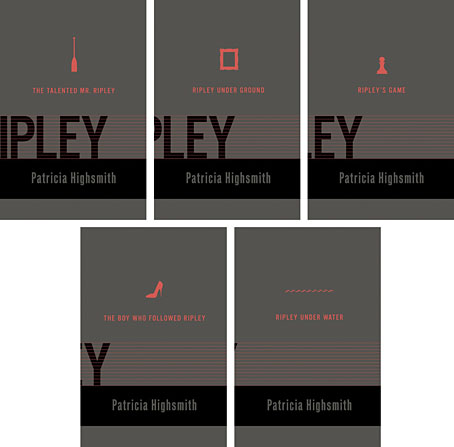

More recent Highsmith covers have tended towards the vague and symbolic, as seen in this blog post by Caustic Cover Critic. I’ve got several of those editions with the sketchy Vintage covers which I don’t like very much, most of them could too easily be applied to another book entirely. The same could be said for the Norton collection of the Ripley novels (below) which go the ultra-minimal route and reduce the contents of each book to a single motif. Individually these motifs might be used elsewhere but taken as a set they become unique. Choosing a high-heeled shoe for The Boy Who Followed Ripley is both funny and fitting but I won’t spoil the story by saying why.

Design by Chin-Yee Li.

A handful of Highsmith links:

• Mavis Nicholson interviews Patricia Highsmith for Good Afternoon in 1978. From those far-off days when British television didn’t regard intelligent discussion as audience poison.

• “The interview was full of drama, as I suspected it might be.” Naim Attalah’s interview from 1993.

• 10 Best Patricia Highsmith Books as chosen by the author’s biographer, Joan Schenkar.

• Patricia Highsmith’s Confessions and Rebellions at Yaddo by Richard Bradford.

• The Patricia Highsmith Recommendation Engine.

• Patricia Highsmith on Desert Island Discs, 1979.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive