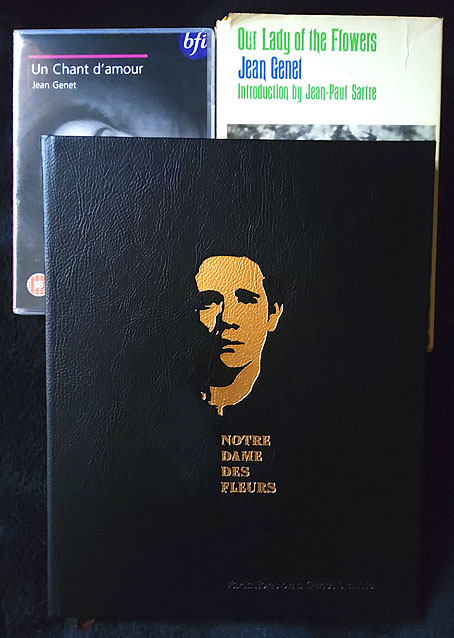

Another week, another book release. Notre Dame des Fleurs is a collection of artistic responses to Jean Genet’s debut novel, compiled and published by Jan van Rijn, for which I contributed three pieces:

Based on the English translation of the unabridged original edition, published in 1949 by Edition Paul Morihien, it is by no means a consistent illustration of the book nor is it a cohesive interpretation in form of a graphic novel. It is a truly personal collection that throws highlights on a beautiful piece of literature, printed in a run of 150 signed and numbered copies. The participating artists in alphabetical order: Michael Ampersant – Antoine Bernhart – Wim Beullens – Susie Bright – John Coulthart – Lauri Elexsen – Rinaldo Hopf – Anja Molendijk – Brane Mozetic – John Thomas Paradiso – Rex – Apollonia Saintclair – Jan van Rijn – Vilela Valentin

Genet’s novel caused a considerable stir when it was first published in France in 1943. Part memoir, part fiction, part masturbation aid, the book was famously written by Genet on sheets of wrapping paper in his Paris prison cell, and is probably the first account of homosexual lives—especially of homosexual erotic lives—lived on their own terms, without any apologies made to straight society or, for that matter, the straight reader. (“Straight” here applies to criminality as much as sexuality.) Antecedents exist, like Teleny Or the Reverse of the Medal, but Teleny is more assertively pornographic, which means it wanders into the fantasy world that porn always creates, a place where desire is everything and introspection doesn’t exist. Genet was writing about the people he knew in Paris before the war, the thieves and pimps and male prostitutes of Montmartre, and doing so in a manner that had to be considered as literature however transgressive the content might be for the literary establishment of the day.

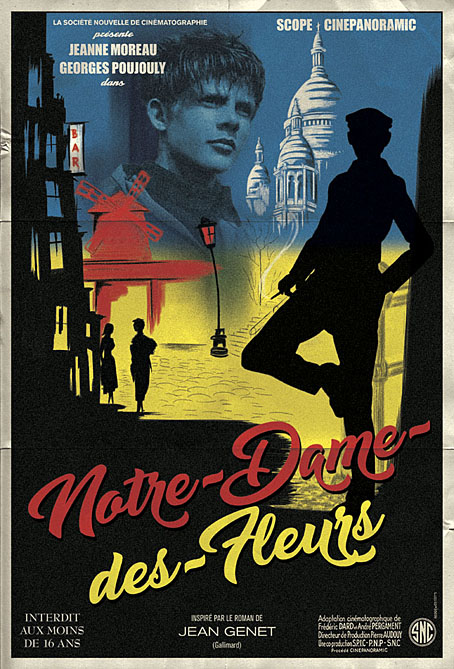

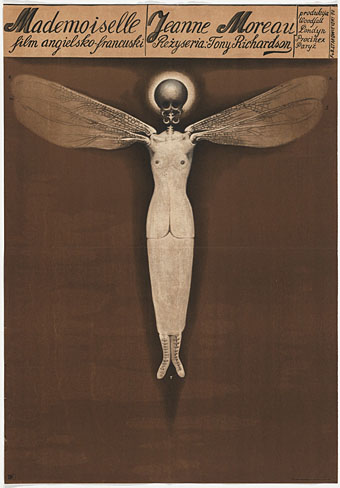

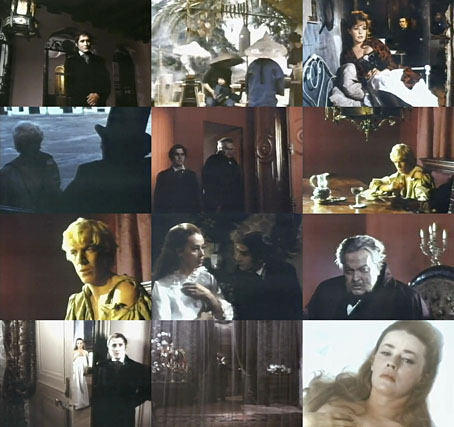

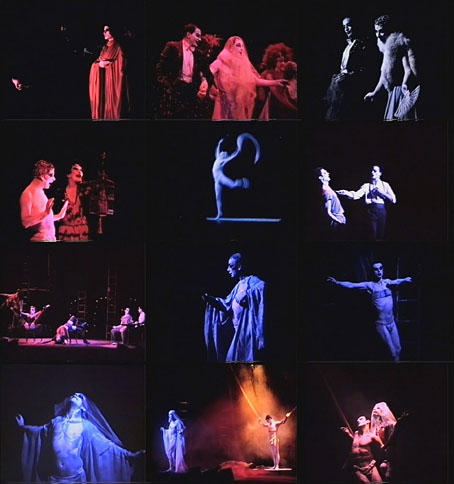

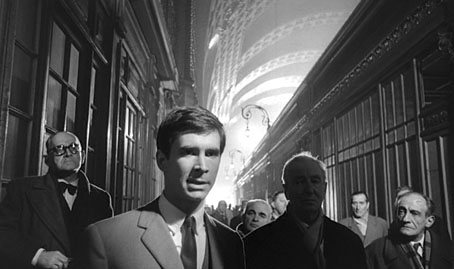

The unique qualities of the novel present difficulties for an illustrator. Literary fiction tends to look inside its characters much more than genre fiction, summoning thoughts, moods and feelings which resist easy depiction in a visual form. I’d first been asked to consider illustrating Notre Dame des Fleurs several years ago for a Graphic Classics collection of crime fiction, a request to which I agreed then had to turn down after deciding that the task of condensing the book into a few pages was a near impossibility. For Jan’s book, rather than illustrate a scene or two from the novel I opted for a conceptual approach. My three pages are intended to be promotional materials from a parallel universe in which Notre Dame des Fleurs was made into a French feature film some ten years or so after its publication, complete with hardcore sex scenes. The latter may seem unlikely but Genet was in the vanguard of presenting gay sex on the cinema screen in Un Chant d’Amour, the 26-minute silent film he made in 1950. He subsequently disowned the film, as he disowned—or “forgot”—many of his creations in later years, but it remains a pioneering and influential work.

Continue reading “Notre Dame des Fleurs: Variations on a Genet Classic”