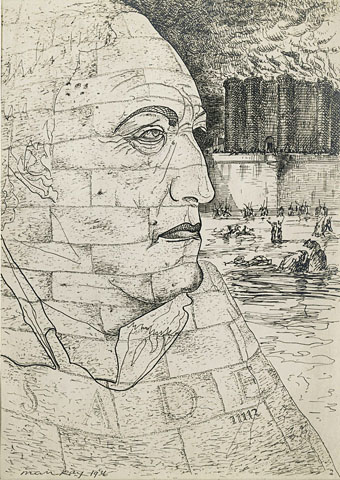

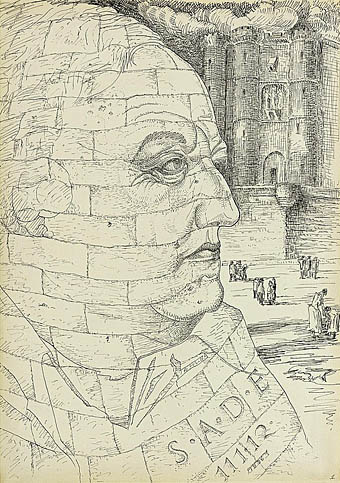

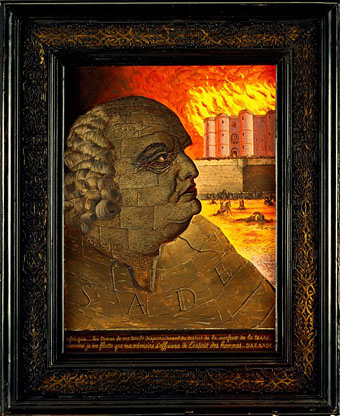

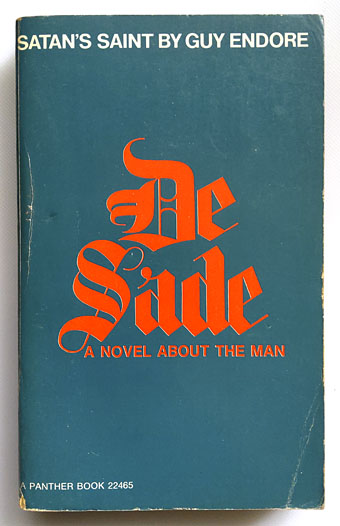

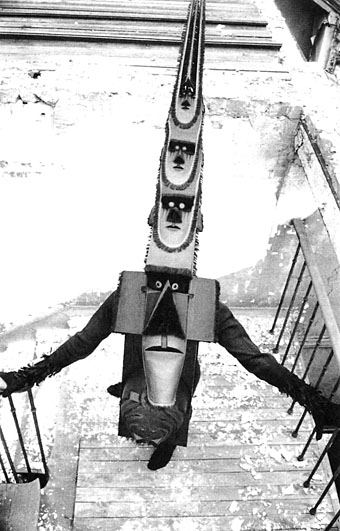

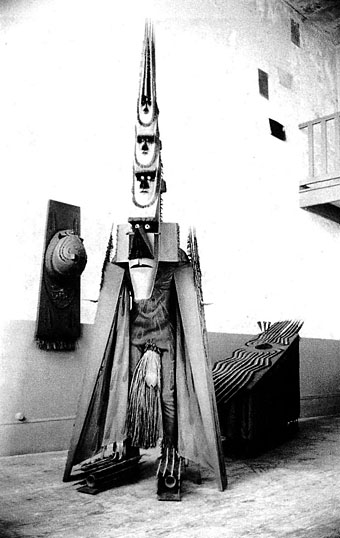

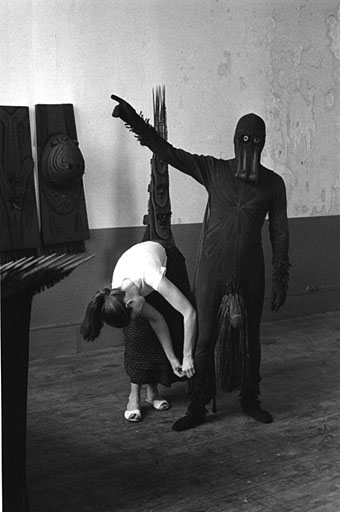

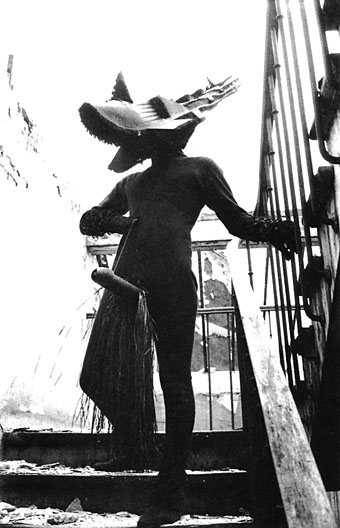

Hommage au Marquis de Sade (1959) by Jean Benoît.

From A Dictionary of Surrealism (1974) by José Pierre:

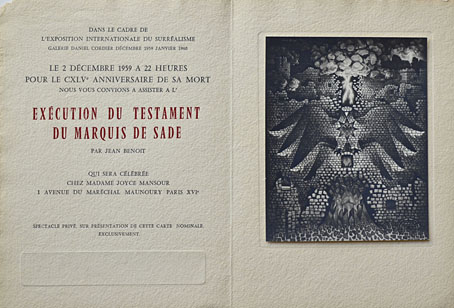

BENOÎT Jean (Quebec, 1922). In Paris, 1949, he undertook a strange enterprise called The Execution of the Testament of the Marquis de Sade which kept him busy for two years. It is a very complicated costume, made up of superimposed coverings and accompanied by important accessories. Each element of the ensemble (medallion, tights, crutches, panels, mask, boots, wings, tomb, push-chair, membrum virile, codpiece, chastity-belt, with tattooing thrown in) transposes some aspect of Sadian thought into plastic terms. The work was to be worn during a special ceremony which took place December 2, 1959, at Joyce Mansour’s, the evening preceding the International Exhibition of Surrealism (“Eros”) in Galerie Daniel Cordier. In 1965 Benoît completed another work for carrying round as a tribute to Sergeant Bertrand, a famous nineteenth-century necrophile, The Necrophile, and a sculpture, The Bulldog of Maldoror, which he presented at the international surrealist exhibition “L’Ecart absolu”, Galerie L’Oeil, in the same year, 1965.

From The International Encyclopedia of Surrealism (2019) by Krzysztof Fijalkowski:

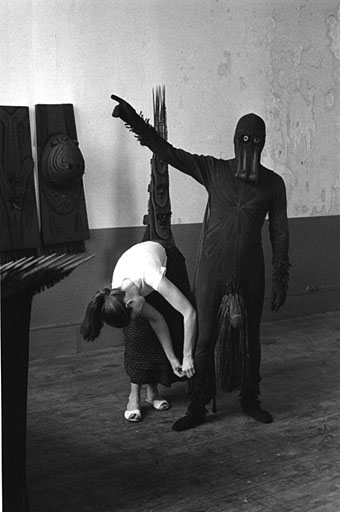

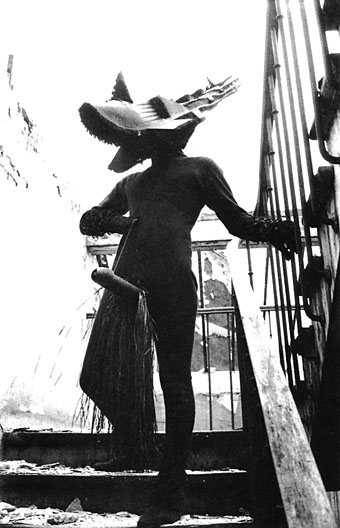

But it is the Execution of the Last Testament of the Marquis de Sade, finally staged in 1959, that lies at the heart of Benoît’s oeuvre. Often cited but rarely analysed, it is one of the most significant works of post-war surrealism. On December 2, at the home of the surrealist poet Joyce Mansour, attended by around a hundred invited guests. the event began with the crescendo of a volcano—a sound recording of street noises made by Radovan Ivsic—followed by a second recording of Breton reading out the Marquis’ last testament, specifying de Sade’s (never heeded) desire for his body to be treated and laid to rest in an anonymous grave. Benoît’s detailed notes specifying every element of his complex and extensive dress and accoutrements were read out loud as [Mimi] Parent helped Benoît, arrayed in this extraordinary costume, slowly remove each item one by one. Layered suits, masks, crutches, panels, ornaments, and accessories made from diverse materials laden with symbolic images and signs evoked intense masked tribal ceremonies and rituals; no photographs of the event were permitted, but Benoît staged its elements for a haunting series of images by Gilles Ehrmann taken in an abandoned building. At the culmination of the ceremony, Benoît revealed himself naked save for a wooden phallus incorporating an hourglass, his body entirely painted and with arrows pointing to the spot over his heart at which he then proceeded to brand himself with the word “SADE.” This performance represented an intense and irrevocable stripping bare of the self in order to restore lost powers, to release de Sade from his incarceration, to seal a community, and to cut through the poverty of contemporary existence in the most dramatic but unrepeatable terms; it is consistent with this sense of a unique and all-powerful gesture that Benoît would not seek to reprise such an event again.

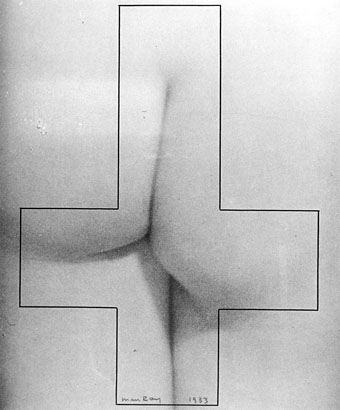

All photographs are by Gilles Ehrmann.

Alain Jouffroy, 1959:

[Autotranslation] I attended a ceremony which took place, in private, in the Parisian apartment of Joyce Mansour, on the occasion of the one hundred and forty-fifth anniversary of the death of Sade. Meticulously regulated by its author, the young Canadian painter Jean Benoît, this demonstration has probably never had its equivalent anywhere. We were a hundred guests. When the doors to the large white room where the ceremony was to take place opened, a great din, a sort of threatening howl from the depths of a volcano, rang out. We were standing upright, shoulder to shoulder, spying on the closed double door that stood in front of us, in the half-empty part of the room.

Among many painters, poets and critics, there were André Breton, André Pieyre de Mandiargues and his wife Bona, Julien Gracq, Victor Brauner, Octavio Paz, Edgar Morin, Matta, Robert Lebel. We hardly spoke. An indescribable feeling of curiosity and embarrassment emanated from certain looks. Then the deafening din ceased. A loudspeaker broadcast the famous “fifth” of the will of the Marquis de Sade, where he asked that we prepare his pit in a “dense thicket”, and that we “sow above” acorns “so,” he said, “that thereafter the ground of the said pit being replenished and the thicket finding itself filled as it was before, the traces of my grave disappear from the surface of the earth as I flatter myself that my memory will be erased from the minds of men.” The voice, which read slowly, solemnly, this fragment of the will, was that of André Breton.

Motionless in the empty space of the room, at the left end, opposite to the one expected to open, a young man stood stiff and motionless behind a conductor’s desk, on which were placed a few loose sheets. After the silence that followed the reading of the will, the door opened, giving way to a fabulous monster. The ceremonial of the execution of the will of the Marquis de Sade, by Jean Benoît, began. The entry of the monster into the room was strangely painful and vehement. Two horns, hidden in his high shoes, made a shrill noise and a deafening noise.

Curved and seemingly crushed by the weight of a mask with four superimposed heads, a veritable totem of anonymity, the monster advanced on sumptuously decorated crutches, pushing before him a huge belly in the shape of an egg, and pulling behind him, by the right shoe, a cart of the same colour as the costume, the wings, the mask and the crutches: silver grey or bronze, and midnight blue punctuated with red; embers under the ashes.

When he almost reached the centre of the empty space and stopped, the hundred silent spectators who watched him found themselves curiously “disoriented” in this apartment where they spoke, so comfortably, a few minutes ago. The embarrassment was really overwhelming: everyone did their best to hide their own, behind a veil of opinions. Then, the ceremony of methodical undressing of the monster began, explained by a text, that the man at the desk read in an equal, neutral, fairly implacable voice, without grandiloquence or familiarity.

A young blond woman with hair drawn back, in a black dress, proceeded, piece by piece, to undress the monster. Each of the elements that she detached was then hung on the wall, disintegrating little by little, in an analytical panoply, the being-totem that bent, obedient, and almost mechanical, to the rotational movements that the young woman made it perform to present spectators with the different faces of the costume.

She removed the mask. Another mask, bewildered, astonished, appeared. Then the face, made-up in black, but for the eyelids and the inside of the blood-coloured ears. Then the body entirely made-up in black, but on which the same arrows as those of the costume were drawn. Finally, the sex, hidden under an enormous black wooden phallus, decorated with straw.

At that moment I heard someone whispering to me, “This is the black moment of the affair.” Jean Benoît, his body stretched by this slow ceremony which he had regulated and meditated every second, then raised the phallus, to simulate the erection, by hanging the wire which was attached to it to a ring with his right hand. Below the phallus, there were two hourglass-shaped mirrors, one in the image of a woman, the other of a man. The young blonde woman lit a fire in a container at her feet, and plunged a phallic-handle iron into it. The flames were reflected for a few seconds in the hourglass mirrors. The phallus fell.

As abruptly as all of the above had been slow, Jean Benoît tore off the red cloth star which was at the location of his heart, threw it into the fire, grabbed the iron with a phallic handle and printed—in the third degree—the letters SADE on the skin, in place of the star. His gaze, which black make-up made more intensely blue and clear, seemed to me piercing like a suddenly drawn blade. Then brandishing Sade’s letter iron which he had just burned, he threw in a loud voice, to the audience: “WHO IS THE IRON FOR?” And slipped out of a small door after throwing the iron into the fire.

There was a moment of confusion. Throughout the ceremony, not a single word had been spoken aloud, apart from the relentless explanatory text, accompanied by quotes, read by the reciter.

Then, weaving his way between the people around him, Matta, who had followed the last part of the ceremony very passionately, entered the empty space of the room, untied his tie, unhooked his shirt collar, and put the iron on his skin. Someone wanted to imitate this but a woman prevented him. The ceremony, apparently, was over.

According to Jean Benoît, who imagined and executed the costume, the entire apparatus symbolizes “the symbolic transfer of the tomb of D-A-F de Sade”, and its colour is “specially designed to take all its intensity in the warm light of the setting sun”. All the arrows which decorate it are vertical, or oblique, or curved: none is horizontal. Thus, each of the details has its symbolic key. Their ensemble invites a resurrection to mythical life. Everything is absolutely faithful to a traditional sign language: just visit an exhibition of masks, at the Guimet Museum, to measure the inventive sum of rites and meanings that Jean Benoît produced with this costume.

The act itself, which consists in burning oneself with Sade’s letters, in a society as talkative and as reluctant to gestures as is the one in which artists are currently living in Paris, is obviously a challenge. Challenge of conformism, challenge of laziness, challenge to sleep, challenge to all forms of inertia, in life as in thought. It is quite obvious that such a ceremony, in absolute contradiction with the vulgarity proper to our time, can only be an object of derision in the conversations of our so-called intellectuals. It is however a reminder of the essential, I mean this mysterious axis around which the human being turns, and which the Hindu Tantrics call the Kundalini—the energy which liberates the sexual act, and which makes it possible for a few seconds to smash the locked doors of our condition.

Fernando Arrabal, Transcendent Satrape of the Collège de ’Pataphysique, 2010:

[Autotranslation] …It took almost a century and a half after the death of the Marquis before—thanks to Benoît—the “Execution of Sade’s Will” took place. December 2, 1959. It was his masterpiece.

…many times Jean Benoît has told Alejandro [Jodorowsky] and I, in detail, about this “execution”…the most ardent ceremony of Surrealism. The story is completed by the one made to me by the painter Matta:

It was one evening at ten o’clock. At the Parisian home of the poet Joyce Mansour.

For this “major” occasion, in reality unique, some of those expelled from the group were welcome. The whole formed by a hundred subversives. We saw Julien Gracq, for the first and last time in a living room. André Pieyre de Mandiargues was living one of his reconciliations with Bona. Octavio Paz was not yet an ambassador. Nor yet editor of “Vuelta”. Nor yet Nobel Prize winner. Neither Jacques Hérold, “Maltraité de peinture”…

The ceremony begins with the entry of Jean Benoît. Dazzling. Dressed in a suit that is in my lair today. African attire three meters high.

According to him, it represented “the symbolic transfer from the tomb of the Marquis”.

Breton reads five points from the will. With authority, a charm tinged with solemnity…and white hair.

So Benoît takes off his clothes one by one. Will he stay naked? He comments on this analysis and each of the pieces. Sacred striptease. Speech enhanced by his inimitable accent. Massive and Canadian. He is more beautiful than ever. A sort of stammering Raphael. Mimi Parent, his partner, is also the focus. Messaline inspired by Cleopatra. Monitoring everything, an eye on transcendence. The different items pile up on the wall in a preset order. By Mishima? The whole thing becomes a broken monument, full of incomprehensible meaning.

Benoît turns into Simeon, mystic and apostate. He camps like the elevated stylite. And his phallus follows the rhythm and the rut of the text. Which his beloved reads him lovingly. Text by Sade. Obviously. Benoît is so faithfully inspired by the message that his phallus rises properly. Straight and hard. And it lasts, when you expect it. The phallus (or penis) is enclosed in a carved wooden case. Impressive by its size. Less than by its performance. At times when the reading becomes the most exciting, the wooden phallus rises in erection. Breton, according to a bad language, would have said:

—”It is extraordinary, not only Jean Benoît is a visionary painter, but also he erects at will”.

A little hallucinated, he does not see a nylon thread tied to Benoît’s finger that directs the comings and goings of his false phallus and his real desire.

Then Benoît approaches the fireplace. He grabs an iron to mark the horned beasts. His scepter carefully prepared. His rigorously polished sculpture. His memento worked meticulously. With topological precision, as he had composed the four letters of this stem: S A D E. At the crucial moment, he marks himself with a hot iron. The name of the Marquis. At the level of the heart. Emotion and general amazement. The painter Matta, moved, rushes. He takes the iron from Benoît’s hands. With a reel he applies the same mark on his flesh. Both breasts smoke for Sade and for eternity.

For a year Benoît had worked with fervour and enthusiasm his instrument intended to mark the breasts and the spirits. Completely absorbed by his design, he does not realise that instead of S A D E his instrument can only print on the flesh the word E D A S.

Until his death yesterday, he carried on his body a “Sade” tattooed with fire and blood. But the name of the divine Marquis was visible only to him. Facing a mirror.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Jean Benoît