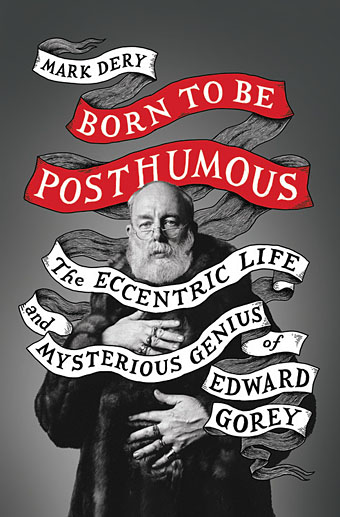

Cover design by Jim Tierney; photo by Richard Corman.

When so many current biographies are recounting the lives of those about whom we’ve already heard a great deal (see the new biography of Oscar Wilde by Matthew Sturgis), a book exploring the career of a previously undocumented yet worthwhile figure is especially welcome. Such is the case with Born to Be Posthumous, Mark Dery’s life of the elusive Edward Gorey: artist, writer, illustrator, book designer, book creator, bibliophile, theatre designer, cat lover and balletomane.

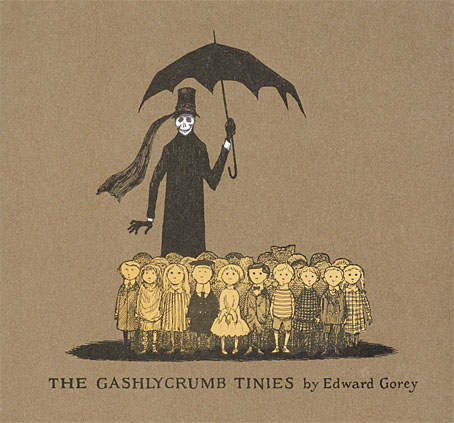

The Gashlycrumb Tinies (1963).

Gorey’s small books have long been one of the more curious fixtures of American culture: many of them look like children’s books but aren’t (unless the child is Wednesday Addams); others look like comic books but they aren’t comics either. The books are sometimes (but not always) Surrealist fables; or brief accounts of irreducible mystery; or sombre inexplicabilities; or camp ripostes to the pieties of Victorian morality; infrequently spiced with black humour and with lurches into outright horror. Gorey delivered his miniature tales in an idiosyncratic drawing style that combines a cartoon-like stylisation with the density of shading found in old wood engravings, a blend that would prove influential as his popularity grew. As Dery notes in his book’s introduction, without Edward Gorey’s work there would be no Lemony Snicket, while Tim Burton would be a skeletal shadow of his present self. (Given the latter’s current output, this might do him some good. But I digress.)

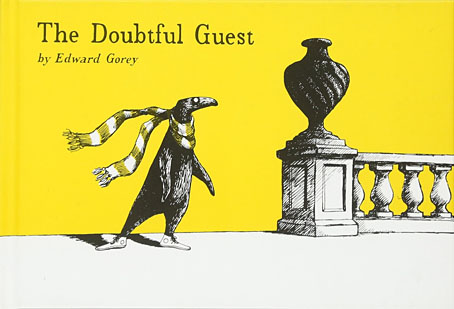

The Doubtful Guest (1957).

In Britain, however, Gorey remains a cult rather than cultural figure, still overshadowed by better-known contemporaries such as Maurice Sendak and Charles Addams. Until the publication of the Amphigorey story collections Gorey’s books were produced in small editions with such a limited availability you were more likely to encounter his art on the cover of another author’s book than within the pages of his own. I became aware of Gorey’s work by gradual osmosis. The first substantial piece I read about him was his entry in Philip Core’s Camp: The Lie that Tells the Truth (1984), in which Core’s mention of an art style “recollecting Victorian engravings” marked Gorey as an artist to be investigated. Two years later he received a longer entry in The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural edited by Jack Sullivan. (Camp and horror: how many other artists sit so easily in both worlds?) But Gorey is absent from many books about 20th-century illustrators, and despite the sequential nature of his work you won’t find him in histories of comic art.

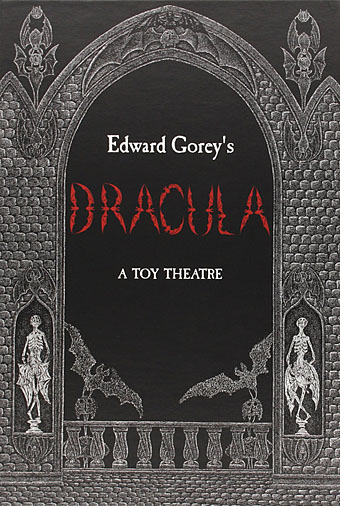

Edward Gorey’s Dracula: A Toy Theatre (1979).

In a way it’s fitting that the work of a man who was adamant in his determination to avoid being pinned down should be so difficult to find. But it’s also a shame that the work of an ardent Anglophile should be hard to find in the country that fuelled his imagination. Among Gorey’s literary favourites Dery lists Jane Austen and Agatha Christie together with Ronald Firbank, Saki, and EF Benson’s Mapp and Lucia novels. (The latter trio are all present in Core’s book on camp, which no doubt makes Gorey camp to the core. Whether he would have approved of being labelled as such is another matter.) I wasn’t surprised by the mention of Saki when so many of Saki’s story titles (The Secret Sin of Septimus Brope) sound like Gorey books, while many of the stories themselves are like Gorey scenarios in prose. Not all Gorey’s work is camp or comic, however; the 32 drawings that comprise the wordless masterpiece of The West Wing (1963) are closer to David Lynch or the “strange stories” of Robert Aickman, the latter an author that Gorey illustrated on several occasions. Dery emphasises how Gorey’s love of silent cinema contributed to The West Wing and other pieces, especially the serials of the Surrealists’ favourite filmmaker, Louis Feuillade.

Continue reading “Born to be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey”