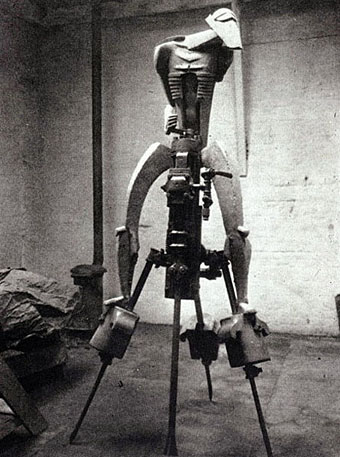

The Rock Drill (original version, 1913–1914).

Jacob Epstein’s Rock Drill (1913-15) was reconstructed in polyester resin by Ken Cook and Ann Christopher in 1973–74. It is the exemplary Vorticist art work. It shows a man on a tripod who is one with his machine. His drill is also his rigid proboscis, his hard, angled phallus. The tripod has weights (embossed Colman Bros Ltd Camborne England) on each leg, just above midpoint—which look like enlarged joints, or a bee’s pollen knee-pads (only available in black).

The rib cage of the figure is exactly like the twin cylinders on a motorbike. He is recognisably human, true, but the human body, with its curves and trim little bum, has been made-over to the angular machine: it is an armoured exoskeleton. The arms are like greaves. I thought of Seamus Heaney’s description of a motorbike lying in flowers and grass like an unseated knight. And I thought too of “Not My Best Side”, UA Fanthorpe’s marvellous poem about Uccello’s St George and the Dragon in the National Gallery. In it, Fanthorpe imagines the young girl being rather taken by the dragon’s equipment, when suddenly, irritatingly, “this boy [St George] turned up, wearing machinery”.

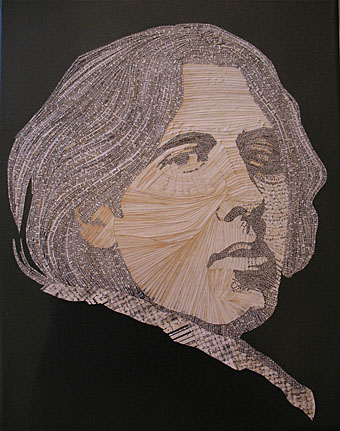

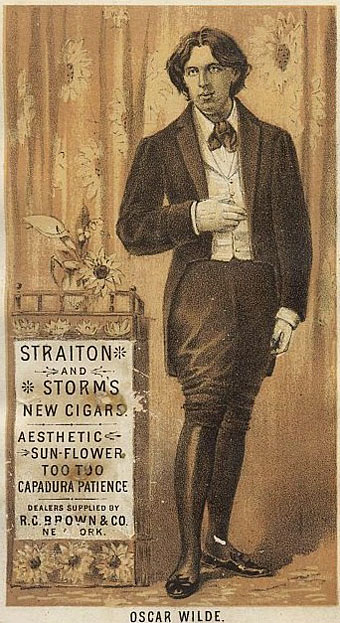

Thus Craig Raine on Jacob Epstein’s unforgettable sculpture. It’s astonishing to think that this piece in its various forms (lost, reworked, reconstructed) is now nearly a century old. Raine was writing about the forthcoming The Vorticists: Manifesto for the Modern World, an exhibition which will be opening at Tate Britain next month. Epstein’s truncated Torso in Metal from The Rock Drill (the full-figure version was destroyed) was one of the handful of sculptures which stood out for me when I first visited the Tate Gallery (as Tate Britain used to be) and it’s since become a piece I always enjoy seeing again. Epstein’s art was frequently controversial, his Oscar Wilde Memorial of 1911 was famously declared indecent, and The Rock Drill would have seem shockingly angular and aggressive to a British art world where aged academicians were still painting medieval fantasies or trying to sculpt like Praxiteles. To us today it looks unavoidably cybernetic even though the word “robot” didn’t arrive until 1920. Flickr has some views here of the reconstructed version which I’d hope is going to be on show at the Tate. In the meantime, there’s Anthony Gormley discussing the work on BBC Radio 3 (via iPlayer) which he regards as the first Modernist British sculpture, and a favourite work of art.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Wildeana #2

• Against Nature: The hybrid forms of modern sculpture

• Angels 2: The angels of Paris