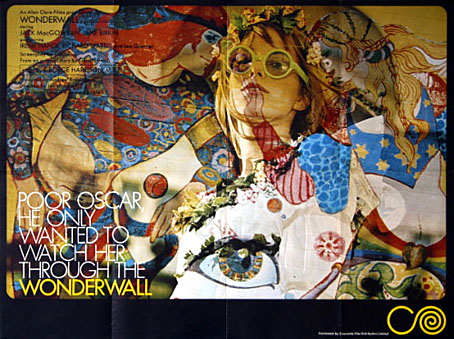

It’s taken me years but the recent obsession with UK psychedelia led me to finally watch Joe Massot’s piece of cinematic fluff from 1968, Wonderwall, a film distinguished primarily for its score by George Harrison (with Ringo Starr and Eric Clapton playing pseudonymously), and its title which was swiped years later by a bunch of Rutles-imitators from Manchester. The story is so slight it would have barely sustained an hour-long TV film: absent-minded scientist (Jack MacGowran) becomes intrigued by his glamorous neighbour (Jane Birkin playing “Penny Lane”; yeah, right…) and knocks holes in the walls of his flat in order to scrutinise her modelling, partying and frequent undressing. Unlike Blow Up (1966, and also featuring Jane Birkin) and the later Performance (1970), both of which attempted to accurately pin down some of the modish aspects of the period, this is a very kitsch piece. That wouldn’t be so bad if it was entertaining kitsch like, say, Smashing Time (1967), but Massott has to resort to scenes of limp comedy and some rather dull dream sequences in order to pad the thing out. Between the handful of actual dialogue scenes there’s a lot of gloating over Ms Birkin’s flesh which no doubt satisfied one half of the audience but by today’s standards is hardly thrilling. Iain Quarrier plays Penny’s duplicitous boyfriend (with a fake Liverpool accent) in his last screen role before he quit acting. Quarrier and MacGowran had appeared together in two of Roman Polanski’s British films, Cul-de-sac (1966) and Dance of the Vampires (1967). In the latter, MacGowran again plays an absent-minded scientist while Quarrier is cinema’s first (?) gay vampire.

An interjection from The Fool.

Of chief interest for me in Wonderwall was the decor and title card decorations by Dutch psychedelic collective, The Fool (who also appear in the party scene), famous for their earlier Beatles associations including the inner sleeve for Sgt Pepper and designs for the short-lived Apple Boutique in London’s Baker Street. I was also curious about the distinctive decor of MacGowran’s flat which contrasts with the psychedelia next door, all dark green walls embellished with Victorian murals and a Tennyson poem—very fittingly a piece called The Daydream—which circles the room.

The professor prepares to attack the wall.

This was particularly interesting in that it made another connection between the psychedelic era and Victorian arts movements, especially from the Aesthetic/Arts & Crafts end of things, but it wasn’t at all obvious whether the connection was an intentional part of the film’s production design or an accident of location and budgetary convenience. Aside from the old-fashioned appearance of MacGowran’s rooms there seemed no reason why his otherwise cultureless character would have any interest in decorating his living space in this way.

The street corner then…

…and now.

The building itself is equally distinctive and an exterior shot conveniently shows a street sign placing the location in Lansdowne House, a Victorian apartment block on the corner of Lansdowne Road and Ladbroke Road in the Notting Hill/Holland Park area of London.

Lansdowne House.

What did the building look like today, I wondered? Google Earth proves indispensable at times like this and it was easy to find, in a street which looks more cramped than it does in the film. The presence of a blue plaque on the wall proved intriguing, a sign that the place once had famous residents. Googling for that revealed this photo which was a real surprise: Lansdowne House at one time contained studios for artists who included Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon, a gay couple and leading lights of London’s fin de siècle art scene (also friends of Oscar Wilde), and another artist, James Pryde, who with William Nicholson worked as The Beggarstaffs. So my suspicion about the Arts & Crafts decor was correct, which means that MacGowran’s flat may have been decorated that way originally and remained untouched since the 1890s. I haven’t seen Rhino’s special edition of Wonderwall which contained additional information about the making of the film, so have no idea whether the history of the building is mentioned there. If anyone does know, please leave a comment. For now I’m quite happy to have stumbled upon another minor link between two of my favourite art decades.

For more visuals, this page has a host of screen grabs from the film as well as some gif animations, all of which manage to make Wonderwall seem more interesting than it is when you’re watching it.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Charles Ricketts’ Hero and Leander

• Images by Robert Altman