The past year would have been busier than usual with the amount of illustration work I had to deal with, but it was made even busier with my having to design this book at the same time. James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art was originally intended to be a modest memorial by Maureen Cawthorn Bell for her artist brother following his death in 2008, but the book grew into a heavyweight volume of 448 pages containing over 800 individual pieces of art: book covers, illustrations for magazines and fanzines, private pieces for friends and relatives, and many sketches or preliminary works, most of which have never seen print before.

Given Jim Cawthorn’s long association with Michael Moorcock, as both friend and collaborator, the task of collating the artwork and editing the book went to Moorcock bibliographer John Davey, who also serves as the book’s publisher. John spent three years locating over 3000 pieces of artwork, large and small. Some of these pieces are now lodged with the Moorcock archives in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, while others may only be found in the pages of the many science fiction and fantasy fanzines that Jim illustrated, copies of which are stored at the British Library. From this body of material Maureen and John selected a core of representative work from Jim’s private as well as public life, although no-one at the outset of the project was expecting the final picture tally to be so high.

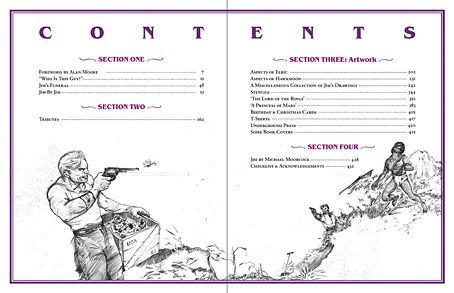

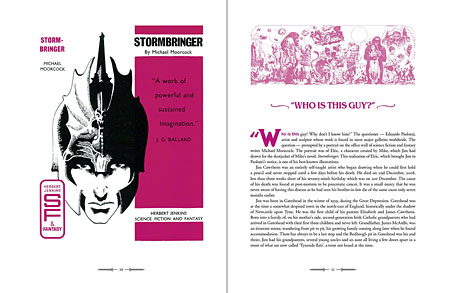

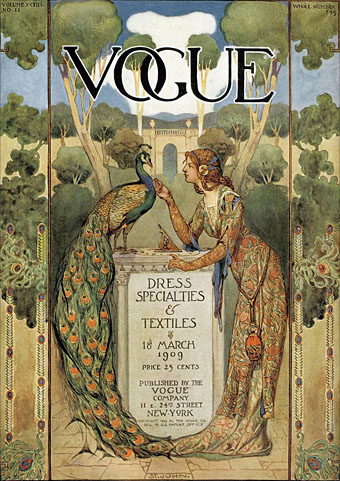

My task as the book’s designer involved making the text presentable (easy) and corralling the artwork (not so easy, and I also had to either clean or colour-adjust every single piece). Maureen had divided the book into several sections, beginning with a lengthy biographical reminiscence. Following this was “Jim by Jim”, a selection of interviews, magazine pieces, some fiction, essays and book reviews. There was also a lengthy extract from Fantasy: 100 Best Novels (1988), a book credited to Jim and Michael Moorcock but, by Moorcock’s admission, mostly Jim’s work. Jim Cawthorn was very well-read, especially in the genres—he was old enough and interested enough to have read The Lord of the Rings when it was first published—and could also present his erudition engagingly for a reader, so the text section of Maureen’s book is far from indulgent.

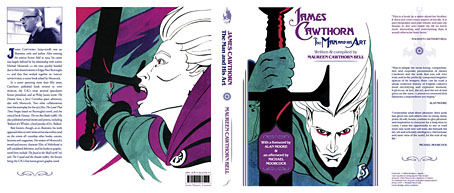

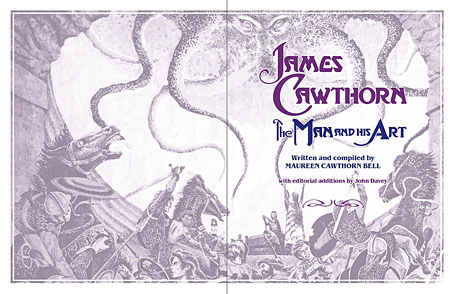

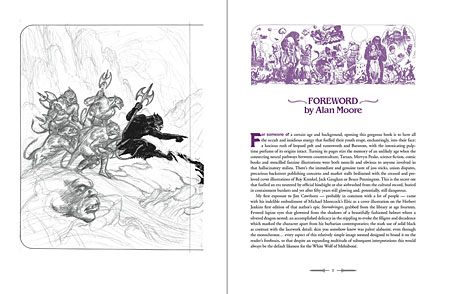

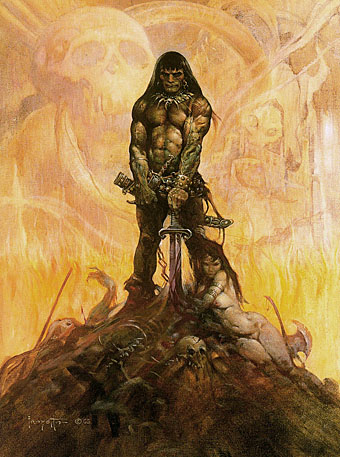

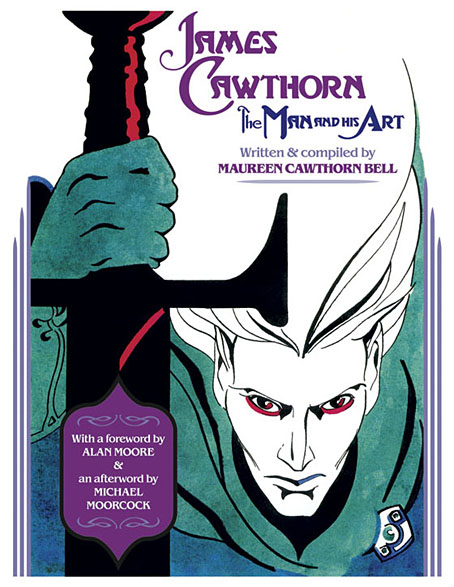

The book design isn’t as elaborate as some I’ve worked on but it didn’t need to be when the pictorial material is rich with what Moorcock calls “wizardry and wild romance”. Maureen wanted a particular picture of Moorcock’s Elric character on the cover so I took details and motifs from some of Jim’s many Elric illustrations to give the book a thematic thread and internal consistency. Cawthorn was present at the creation of Elric in the early 1960s; he not only provided Moorcock’s characters with their first illustrations but even helped plot one of the earliest stories, Kings in Darkness.

Page numbers are framed by the swords from the Elric stories.

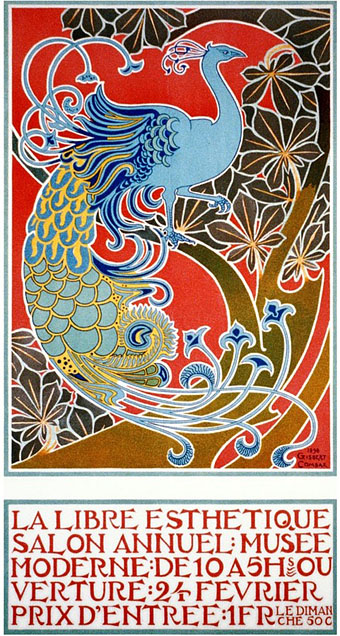

Using motifs such as the sword silhouette and Elric head is something I frequently do with book designs but for this book I also went to the trouble of creating a one-off font for the drop capitals based on Jim’s hand-drawn lettering. Jim drew titles and other lettering throughout his career, so again this was a decision warranted by the book’s contents. The few times we met I never asked him about this but I’ve always thought his lettering designs were derived from the stylised titles that J. Allen St. John created for many of the early Edgar Rice Burroughs books. Jim spent most of his life drawing Burroughs’ characters, and was very familiar with the work of Burroughs’ original illustrators. I was hoping to find a title design of Jim’s that I could rework for the book’s title but none of the examples worked as well as I hoped. For this reason the title lettering is based on different styles from the John Carter novels that were Jim’s favourites among Burroughs’ works.

Other features include a foreword by Alan Moore, an afterword by Michael Moorcock, a gallery of Jim’s Lord of the Rings drawings and character sketches from the early 1960s (which predate all others bar those by Tolkien himself), artwork for Hawkwind (including Dave Brock’s “Meliadus” T-shirt), and even a handful of photos from the set of The Land that Time Forgot (1975), the ER Burroughs-derived feature film scripted by Jim with Michael Moorcock. The page samples here are necessarily few given the size of the book.

For the moment James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art is available exclusively from publishers Jayde Design at a special pre-publication price of £20. After publication on 6th August the price will rise to £35. Further page samples follow.