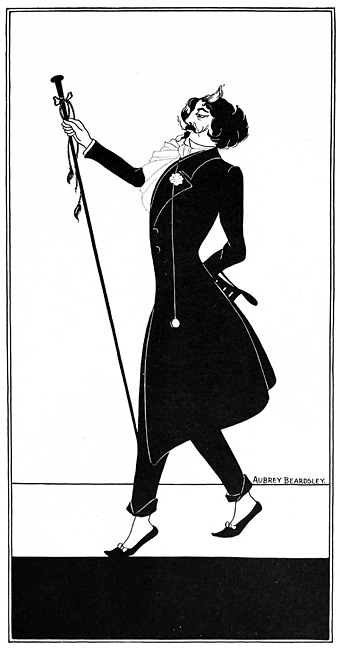

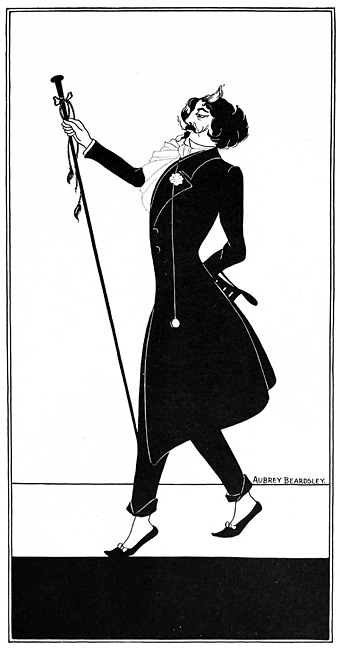

Cover of Fifty Drawings by Aubrey Beardsley (1920).

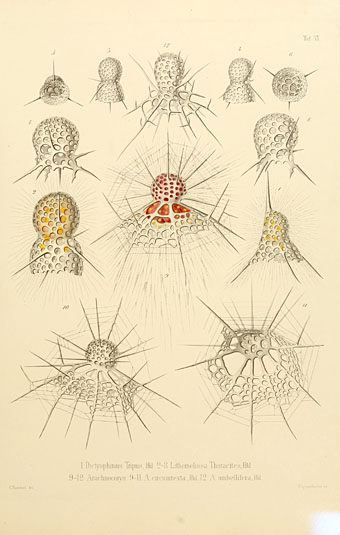

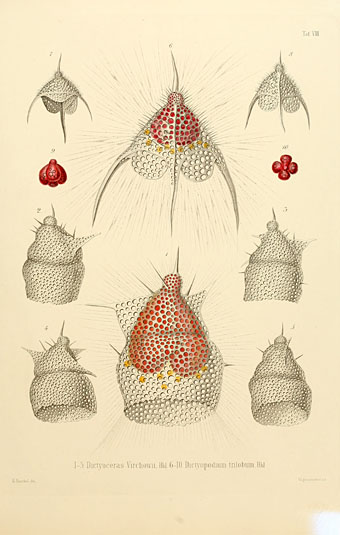

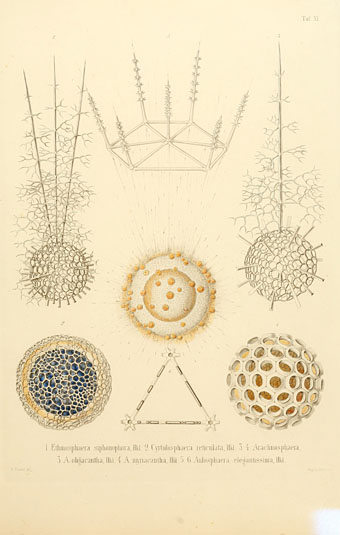

I’ve long been fascinated by fakes and forgeries especially those one finds in the art world, when the ability to imitate another artist’s work succumbs to the temptation to defraud. Artistic forgeries succeed best when there are convenient gaps in an artist’s career, and when the historical record is vague enough to plausibly allow the existence of a lost or neglected work. The fake Aubrey Beardsley drawings that were presented by HS Nichols to the New York art world in 1919 are unusual for offending both these criteria. Beardsley and his work will be subject to renewed attention in March when Tate Britain stages the largest exhibition of his drawings for 50 years, and it was news of this that reminded me of the Nichols fakes. I know the drawings from an appendix in The Collected Works of Aubrey Beardsley (1967), edited by Bruce S. Harris, which presents almost everything that Nichols published in a subscriber-only collection, Fifty Drawings by Aubrey Beardsley, in 1920. Nichols had been in the Beardsley milieu in the London of the 1890s, and was for a short time a partner of Leonard Smithers, the publisher and pornographer who not only published Beardsley’s later works along with The Savoy magazine, but also commissioned the notoriously “obscene” Lysistrata drawings. Smithers was, by Victorian standards, a scoundrel, but also an aesthete, whereas Nichols seems to lack any redeeming qualities. One of the curators of the Tate exhibition, Stephen Calloway, describes Nichols in his 1998 study, Aubrey Beardsley, as “scurrilous”, and provides an account of the Nichols fakes:

That Beardsley’s style was more or less inimitable was sadly proved by almost all those, and there were many, who attempted to fake his work. From the period immediately after the First World War, at a time when AE Callatin and a number of other American collectors were beginning, really for the first time, to make Beardsley originals more valuable, forgeries began to abound. In 1919 a celebrated fraud was attempted when HS Nichols reappeared on the scene, claiming to have an important and sizeable cache of previously unknown Beardsley drawings. They were put on a show in New York. Considerable excitement was generated, especially when doubts about the authenticity of the works began to be voiced in several important quarters.

Denounced as fakes by Callatin, Joseph Pennell and other connoisseurs, these hopelessly inept specimens of the forger’s pen were vigorously defended by Nichols, who claimed in the New York Evening Post, “I know a great deal more about Beardsley than either Mr Pennell or Mr Callatin, but I absolutely decline to make known to the world what I do know”. In fact, he claimed to have had more intimate dealings with the artist than even his erstwhile partner Smithers. The drawings, fifty in number, were published in an expensively produced album, like the Van Meegeren Vermeers; it is difficult now, with hindsight, to see how anyone could possibly have been taken in even then. But, in spite of a useful essay on How to Detect Beardsley Forgeries by the great Beardsley scholar RA Walker, which specifically alludes to these efforts at deception, examples from this very group and others of their like still circulate and surface from time to time.

The note in the Harris book refers to a dismissal of the fakes by Oliver Brenning in the September 1919 edition of Vanity Fair, an article which may be read here (PDF). As for the Nichols book, this turned up recently at the Internet Archive so it’s now possible to see all the fakes in one place. Whoever was responsible for the Nichols drawings (I’ve seen Nichols himself credited) isn’t merely a bad imitator but is also a bad artist, with many of the drawings being remarkably graceless and inept. Beardsley’s art, especially his early work, is often grotesque (“I am nothing if I am not grotesque,” he once said) but it is never ugly. When they’re not being ugly the Nichols fakes assault one’s credulity by showing a pair of young women wearing clothes of a style unknown in the 1890s (Plate 15: “The Twins”), or plagiarising Alphonse Mucha (Plate 49: “Design for a Church Window”). I haven’t checked but I think another of the drawings may be a copy of a piece by Eugène Grasset.

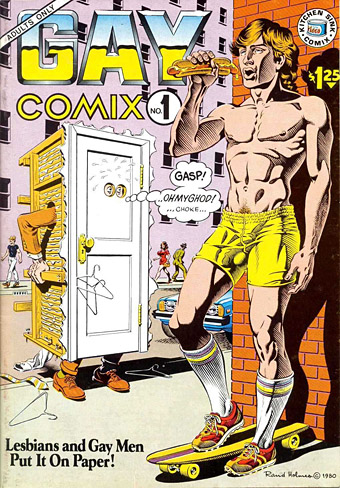

Whistler by unknown artist (not by Aubrey Beardsley, despite the signature).

Stephen Calloway is correct when he says that the fakes continue to circulate today, mechanical (and digital) reproduction having given them a life they really don’t deserve. (This post might be accused of extending that lifespan.) The Whistler portrait above is one of the more convincing examples which no doubt explains why it was credited to Beardsley in Nick Meglin’s The Art of Humorous Illustration (1973), a book from a reputable New York publisher, Watson-Guptil.

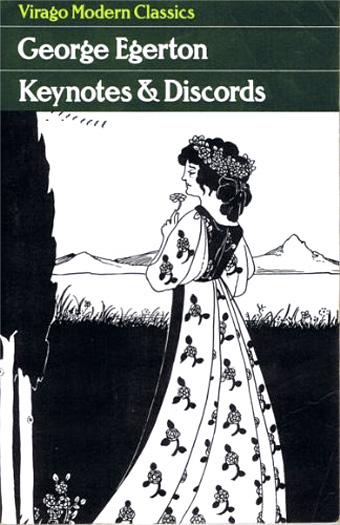

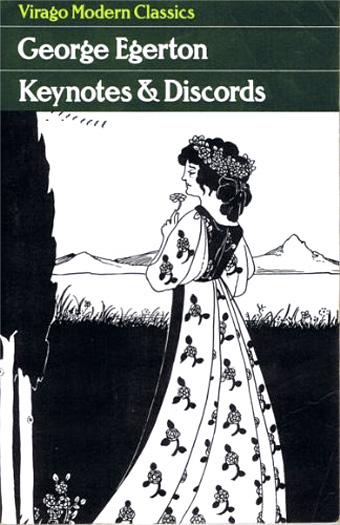

When Virago published Keynotes & Discords by George Egerton in 1995 they used another of the fakes on the cover. This was particularly ironic when Egerton’s stories had been first published in John Lane’s Keynotes series, a line of books that not only took their name from the first Egerton volume but which were illustrated by Beardsley himself. The worst example of proliferation I’ve seen in print was the Beardsley postcard book published by Taschen in the 1990s which scattered the Nichols fakes among genuine Beardsleys, thus ensuring that the uninitiated would continue to litter the world with the things. Today we have Pinterest, home of the erroneous credit. I doubt the Tate exhibition will draw any attention to the fakes but now that Nichols’ book is online it’s easier for those who suspect an attribution to assuage (or confirm) their suspicions.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Aubrey Beardsley archive